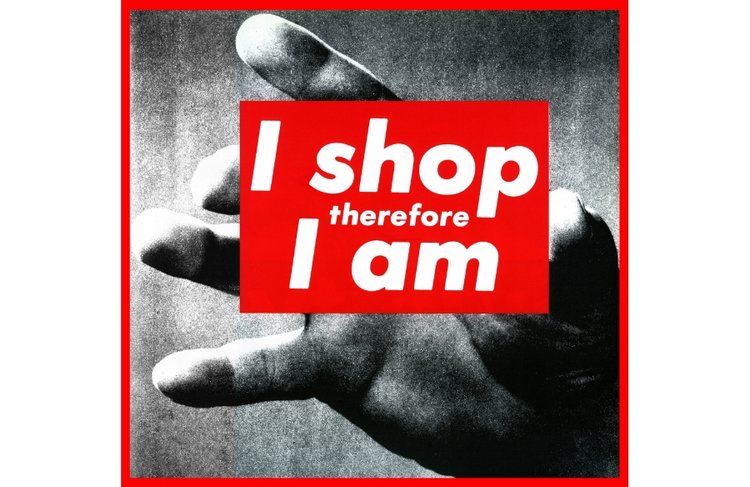

Barbara Kruger technically did it first. Beginning in the 1970s, while she was working in New York as a graphic designer for popular magazines, including Condé Nast’s Mademoiselle, Kruger took the Futura font – one created by German company Bauer Type Foundry – paired it with “scenes from banal consumer life,” and thereby, “reframing the implied motives of her subjects,” the New Yorker’s Jamie Lauren Keiles put it years later, reflecting on the work of the esteemed artist. It was not until 1981, however, that Ms. Kruger debuted her white Futura text in-a-red-box designs and then again, not until 1990 that she introduced one of her most famous creations: her “I Shop Therefore I Am” work.

Meanwhile, across town, British transplant James Jebbia was toying with the idea of launching his own brand. He had moved to New York in 1983 – when he was just 19 years old – and within a few years, had embarked upon his first retail venture, Union, the retail store he opened on Spring Street in Soho, with his partners Mary Ann Fusc and Shawn Stüssy. Inside Union – which has continued on in Los Angeles (after the closure of the New York location) under the ownership of Chris Gibbs, who had previously worked for Jebbia – you could find English clothing brands alongside the likes of Stüssy’s eponymous skatewear/surfwear brand.

Nearly 10 years after he first landed in the U.S. – or to be exact, in Staten Island, where he rented an apartment for $500 – Jebbia found himself itching for something new. “I always really liked what was coming out of the skate world,” Jebbia told Vogue. “It was less commercial—it had more edge and more fuck-you type stuff.” So, he decided to open his own skate shop.

With a bunch of young neighborhood skaters as his first employees and a stock limited exclusively to t-shirts, Supreme opened its doors on Lafayette Street on April 21, 1994. The front door of the small shop bore a bumper sticker-looking red rectangle that read “Supreme” in white. “I just was like, ‘Hey, that’s a cool name for a store,'” James Jebbia told Interview magazine in 2009. The red rectangle paired with the white Futura font was quite obviously a(n) (unauthorized) play on Kruger’s art, and Jebbia would later acknowledge (in connection with a lawsuit) that Supreme’s soon-to-be wildly famous and highly lucrative logo was “based directly” on Kruger’s work.

Battle for the Name

Much has been made over the years as to the status of Jebbia’s rights (or more accurately, Chapter 4 Corp.’s rights) in the various Supreme trademarks – from the brand’s word mark to the box logo. Most reports point to the similarities between Supreme’s red-and-white box logo and Kruger’s artwork, declaring that Kruger is the reason why Chapter 4 Corp. did not maintain federal registrations with the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (“USPTO”) for box logo mark for years. That is, of course, not the real story.

It is true that Supreme has been forced to fight for its trademark rights. As Jebbia told Interview in 2009, Supreme “is a good name, but it is a difficult one to trademark.” That difficulty is not merely as simple as pitting the buzzy streetwear brand against the likes of Ms. Kruger. The opposition, so to speak, has been greater than that. In fact, one of the first trademark-related battles that came about in connection with the Supreme name involved not Kruger, but a Las Vegas-based eyewear brand.

In September 2011, Pryor Cashman, the high-powered New York-based law firm that represents the likes of Kanye West, Jay-Z, and Beyoncé, among others, filed a trademark application for registration with the USPTO on behalf of Supreme for the word “SUPREME” for use on eyewear, sunglasses, and graphics for cellphone cases and laptops, among other things. Within a few months of filing, Supreme faced push back in the form of an Office Action, a letter sent by the USPTO notifying the brand that its mark was not registrable (on a preliminary basis, at least) because it was too similar to an already-registered trademark in the same class of goods.

Turns out, Durchin Enterprises, a Las Vegas-based company, which does business as Vegas Style Fashion Eyewear, had been using “SUPREMO” on its own eyewear and related accessories and had a registered trademark for the name. As noted by the USPTO, because the English translation of the word “SUPREMO” is “SUPREME,” Jebbia’s Supreme would be barred from receiving federal trademark protection for its mark. In accordance with the trademark doctrine of foreign equivalents, a mark in a foreign language and a mark that is its English equivalent may be held to be confusingly similar.

Supreme was out of luck, and shortly thereafter, withdrew its application for the “SUPREME” trademark from the USPTO.

From this came a string of subsequent losses for Supreme. The USPTO refused to register its “SUPREME” mark for use on everything from calendars (and bumper stickers to passport cases and paperweights, etc.) and dinnerware to jewelry and duffle bags (and backpack and purses, etc.). In doing so, the USPTO pointed to a laundry list of others – from industrious individuals to an array of established companies – that were already using the mark, none of which were Kruger.

But it was not all loses for Supreme from a registration perspective. The brand managed to score one big win: its “SUPREME” trademark for use on clothing, an application for which was also filed in September 2011, was registered by the USPTO in June 2012. That mark, along with the “SUPREME” mark for use on skateboard decks, has since become “incontestable,” which means that the marks are – more or less – immune from being challenged by others in terms of their validity.

It also has not been a loss for Supreme from a brand-building perspective; it is worth noting that in the U.S., trademark rights are not born from filing and receiving trademark registrations but from actually using the trademarks, themselves, and using them consistently, and all the while, getting consumers to associate those marks with a single source (i.e., your brand), which Supreme has been doing for more than two decades, thereby, engaging it to amass trademark rights with or without registrations. Registration would, of course, follow. Supreme has since received registrations for the “SUPREME” trademark for use on “all-purpose sports and athletic bags; duffel and travel bags; fanny packs and waist packs; backpacks; knapsacks; wallets,” skateboard decks, and retail store services, for instance.

The Box Logo

It was only after these developments that the Supreme box logo trademark came into play in a trademark registration sense. While Jebbia’s brand had been using the box logo from the very outset it was not until March 2013 that Supreme filed to register the box logo – or a “mark consist[ing] of the word ‘Supreme’ in white block letters against a red rectangular background” – with the USPTO for use on “women’s, children’s and infant’s wear.”

Again, Supreme was hit with an Office Action from the USPTO, which was refusing to register the mark. However, this time around, something was different. Instead of finding that the proposed trademark was too similar to others’ previously registered marks, the USPTO initially refused to register the mark because it was “merely descriptive.” Descriptiveness is a bar to registration because the purpose of trademarks is the identify the source of a company’s goods (and thereby, distinguish them from those of other manufacturers), not to describe them. The USPTO held that the word “Supreme” does not identify the brand at play but instead, “describes a quality … of [the brand’s] goods and/or services.”

In other words, as a USPTO examining attorney stated in the Office Action, “When the word ‘Supreme’ is used on or in connection with clothing, it immediately conveys to consumers that applicant’s goods are ‘of the highest quality,’ which is a laudatory use of the term.”

Unsatisfied with the USPTO’s preliminary finding, Supreme called foul. Fighting back, the brand was able to convince the trademark office that based on an existing registration – the “SUPREME” trademark for use on clothing – that its name was not merely descriptive but actually, an identifier of source of the goods it sells. Much like with the “SUPREME” word mark, the brand has since been awarded federal registrations for use on “all-purpose sports and athletic bags; duffel and travel bags; fanny packs and waist packs; backpacks; knapsacks; wallets,” skateboard decks, retail store services, and of course, a wide range of clothing items, for the box logo, as well.

To clear up one of the most highly mis-reported things about Supreme and its widely used (and widely copied) red box logo: Nowhere in any of the USPTO documentation does the trademark office reject any of Supreme’s box logo applications because of its similarity to Kruger’s work. Nowhere.

Supreme Bitch

Even with that in mind, Kruger’s influence on Supreme’s branding is undeniable. Despite such marked similarities, the now-73-year old feminist artist remained mum … until relatively recently, that is. In fact, Kruger, herself, did not enter the picture until the spring of 2013, just a few months after Supreme filed its first trademark application for registration for the red box logo. The timing of that filing was not so random. Two months, almost to the day, after Supreme’s application for the box logo was filed with the USPTO, the brand – or better yet, Chapter 4 Corp., which does business as Supreme – slapped another brand using the Supreme name and box logo with a strongly-worded lawsuit.

Turns out, while Supreme was busy building out its arsenal of trademark protections and consistently courting a wildly dedicated and ever-growing following, Leah McSweeney had been in the process of launching her own brand, Married To The Mob, a female-centric streetwear label. Some of its most popular wares were t-shirts and snapback hats featuring the words “SUPREME BITCH” in white writing positioned inside a red rectangular box. The design was something of an homage to Supreme, which was ten years old when McSweeney first debuted her “SUPREME BITCH” designs. It was also a commentary on “the misogynistic vibe of Supreme and the boys who wear it,” McSweeney would reveal in connection with the suit that Supreme’s corporate entity filed against her and her brand in a New York federal court in March 2013.

Nit long after a “SUPREME BITCH” hat was spotted on Rihanna and in the midst of the brand swiftly garnering fans on social media and beyond, McSweeney – not unlike Supreme – looked to the USPTO to protect her trademark rights, filing three registrations for the “SUPREME BITCH” mark. In December 2012, she filed an application for the words “Supreme Bitch” for use on apparel. A month later, she filed an application for the words “Supreme Bitch” for use on hats and shirts, and still another month later, in March 2013, she filed to register the red box and white lettering “SUPREME BITCH” logo.

As it turns out, Jebbia was already acquainted with McSweeney’s design. In fact, the story goes that he had even approved the original design, and stocked it at Union years prior, which is why it was striking when Supreme’s corporate entity Chapter 4 Corp. sued McSweeney for trademark infringement and dilution, counterfeiting, and unfair competition, among others claims, seeking a whopping $10 million in damages and a court order requiring that McSweeney remove the designs from her e-commerce site immediately and permanently.

Recalling that he had, in fact, given McSweeney the go-ahead to use the logo, Jebbia said he had a change of heart once he saw the breadth of the “Supreme Bitch” merch. “I thought it was just going to be a one-off. Now it’s on hats, T-shirts, towels, mugs, mouse pads,” he said around the time of the lawsuit filing. According to Jebbia, the damage ran deep because McSweeney’s wares were not merely infringing Supreme’s valuable trademarks, she was “trying to build her whole brand by piggybacking off Supreme.”

McSweeney had a different take, telling New York Magazine at the time, “There’s this one Barbara Kruger piece that says, ‘Your comfort is my silence,’ and I cannot help but think that I’m being silenced by Supreme with this lawsuit. I don’t have $250,000 to litigate this case, and they know that.” The “bottom line,” according to McSweeney: “I don’t think Supreme should be able to squash free speech or my right to utilize parody in my design aesthetic. It’s one of the most powerful ways for me to comment on the boy’s club mentality that’s pervasive in the streetwear/skater world.”

In a formal response to Chapter 4’s complaint, McSweeney and Married to the Mob denied the majority of Chapter 4’s assertions, and set out an array of affirmative defenses, arguing, among other things, that the “Supreme Bitch” design is a parody, and thus, shielded from trademark infringement and dilution liability. A parody of what exactly? According to their answer, McSweeney and Married to the Mob argued that the “Supreme Bitch” logo and t-shirt “originated as a criticism and parody of the male-dominated and often misogynistic skate culture and Supreme brand.”

In addition to the affirmative defenses, McSweeney has asked the court to declare that her “Supreme Bitch” logo was, in fact, non-infringing.

Within three months of Chapter 4 filing suit, the parties settled the matter out of court. While the terms of the parties’ settlement are confidential, it appears from Married to the Mob’s website that it may have agreed to cease its sales of any the box logo-looking “Supreme Bitch” graphic. It was also noteworthy that a month before the news of the settlement broke, McSweeney had withdrawn two of her trademark applications for “SUPREME BITCH,” having already withdrawn one a few months prior.

But What About Barbara Kruger?

Funny enough, while Kruger is often cited as the reason for Supreme’s trademark troubles, she is maybe one of the least involved parties in the story of Supreme’s legal trajectory. That changed in May 2013. After years of silence, Kruger spoke out in light of the suit that Supreme filed against McSweeney and her brand. When asked about the lawsuit, Kruger provided a now-iconic statement to streetwear site Complex. Her comment: “What a ridiculous clusterfuck of totally uncool jokers. I make my work about this kind of sadly foolish farce. I’m waiting for all of them to sue me for copyright infringement.”

That is not all that Kruger had to say, though. She followed up in November when she staged a series of “live performances,” obvious plays on everything that is Supreme. One of four Kruger works scattered across New York City was a pop up shop, entitled, “Untitled (The Drop),” a reference to Supreme’s model of selling products by way of weekly drops of merchandise – which spawn lines outside of its New York shops, and cause buying frenzies on re-sale sites.

“The most Insta-famous is Untitled (Skate), a skate park on the Lower East Side plastered with Kruger’s work. There’s also a billboard near the High Line, Untitled (Know, Believe, Forget), and a school bus with slogans that range from idioms about war to “OMG, TMI” on its back door. (The MTA is also dispensing Kruger-printed MetroCards at certain locations, although this is not technically part of the Performa series.),” wrote Vogue’s Steff Yotka at the time. You may recall that Supreme released MTA cards last year, as well.

The pop up, itself, was complete with everything from $40 t-shirts and $70 hoodies (the profits from which were donated to charity) to the most buzz-worthy item: Skate decks emblazoned with the word “JERK,” yet another poke at Supreme.

As for whether Kruger is still (jokingly) waiting for Supreme – complete with a newly-pocketed $500 million investment from the Carlye Group and a ton of high fashion buzz following its collaboration with Louis Vuitton – to file an infringement suit against her, it is unlikely. She is the original, after all, even if – in 2018 – streetwear aficionados associate the white Futura font against a red box more with Supreme.