image: JDbags.com

A crop of new(ish) internet retailers has burst on to the scene. Most are based in China, producing low-cost imitations of garments from catwalks and fast-fashion stores alike. No one from Hermès to H&M is safe. Romwe, in particular, is a prime example. With its extensive blogger network, Romwe has managed to raise its profile exposure within a short amount of time and, more importantly, without having to face any detrimental litigation as a result.

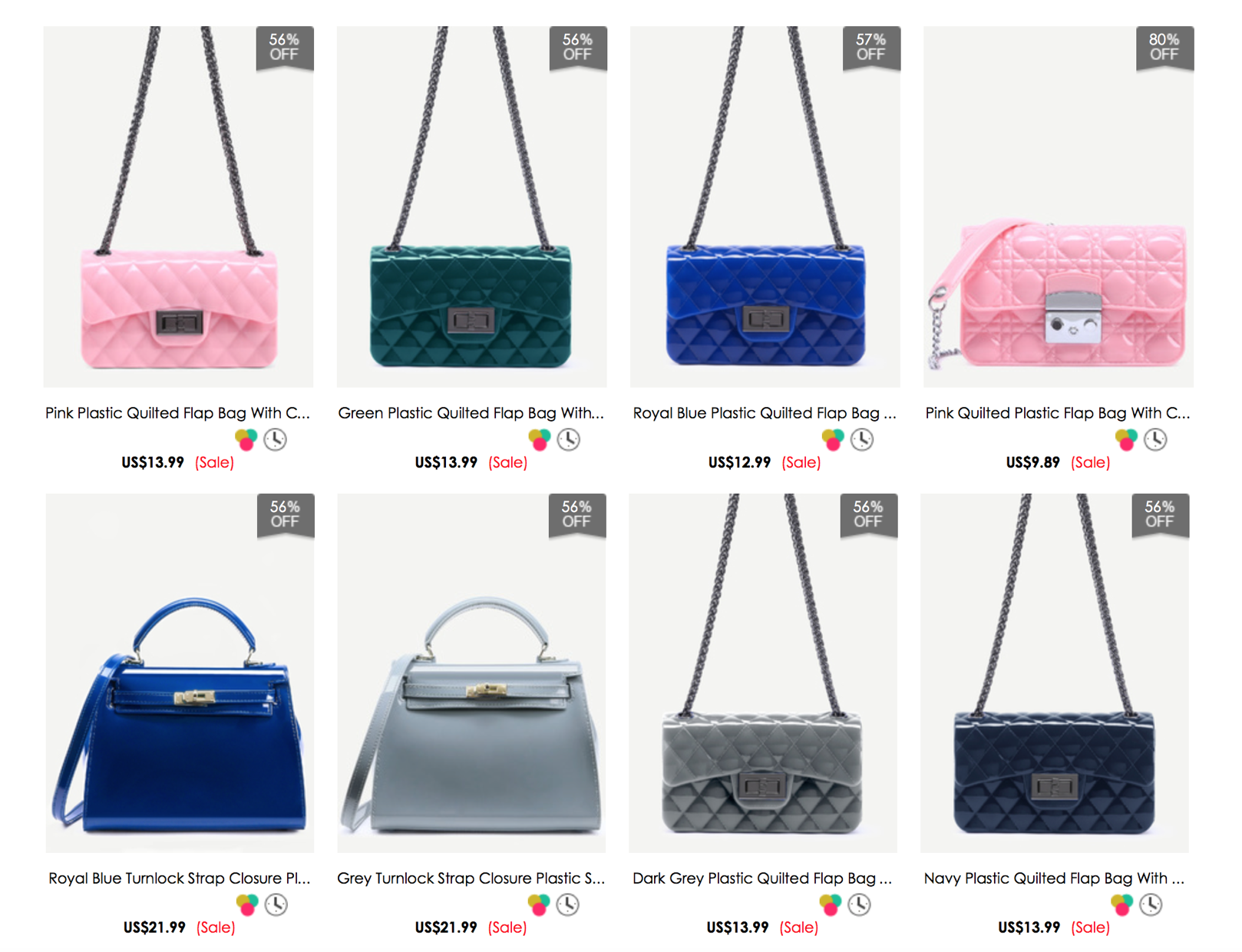

Romwe’s website tagline – “From Runway to Realway” – is hardly an exaggeration. A brief scan of the website reveals no shortage of potential trademark and trade dress infringements (the lookalike Hermès, Louis Vuitton, Christian Dior, Fendi, and Chanel bags being among some of the most problematic); copyright infringements; and UK design right infringements (similar to a design patent for those based in the U.S, but they do not necessarily require registration), all at dirt-cheap prices.

Among those susceptible to an infringement litigation include, Prada-style sunglasses, a scarf adorned with the famous trademarked-protected Burberry check, t-shirts bearing Nike’s trademarked slogans, Ralph Lauren’s branding, and Gucci’s red and green stripe trademark. All of which are blatant and obvious and would almost certainly make for easy wins in court for the targeted brands.

As such, the following inquiry seems reasonable: Why aren’t brands sending cease and desist letters – letters sent to alleged wrongdoers describing the alleged misconduct, demanding that the alleged misconduct be stopped, and providing notice that legal action may and will be taken if the conduct in question continues – to sites like Romwe and getting the infringing goods removed? In truth, brands are probably doing that repeatedly, and have likely been ignored. It goes without saying that such threats of litigation do not tend to deter the operators of these companies as they are based entirely on the sale of low cost copies.

How else do Chinese sites like Romwe continue to get away with such blatant infringement? Well, consider their home turf. Enforcing intellectual property rights in China is notoriously difficult and expensive, and native website operators know this. In theory, enforcement should be easier and less costly. China is a signatory to the Paris Convention, under which a person from a signatory state can apply for a trademark in another signatory state (in this case, China) and will be given the same enforcement rights as if they were a national of that country.

China is also a signatory to the Berne Convention, which means that China recognizes the copyright of “authors” (this term includes designers, artists, etc.) from other signatories in the same way they as they recognize the copyright created by their own nationals. In Europe, articles of clothing are protected by unregistered design rights, which protect the shape and configuration of a garment. Whereas China has a system for the protection of design patents, but these must be registered to gain protection – a cost not attractive to fashion brands who will have moved on to showing a new season by the time patent protection is granted for a single garment.

images courtesy of romwe.com

Litigation is expensive and the cost of litigating in a foreign jurisdiction is even more so. Even if any of the aforementioned brands were to file suit against the owners of Romwe, the chances that the defendants are identifiable and would appear in court are extremely unlikely. We know this given the very strong pattern of behavior in similar cases, almost all of which are resolved by way of default judgments, after the defendants fail to respond to any notifications of the lawsuit or appear in court.

As such, brands are more likely to utilize other means at their disposal before resorting to litigation. One option available to rights holders is contacting the internet service provider (“ISP”) of the infringing website to inform them that they are hosting infringing material, and request that it be removed from the website. This usually results in a fast response from the ISP and a takedown of the entire website. However, operators of such websites tend to maintain a large number of similar websites, selling similar goods.

Moreover, the operator(s) of the infringing website will quickly find a new ISP and be operational again within a few hours, turning the process into a time-consuming game of whack-a-mole for brands that results in little progress in the grand scheme of their enforcement efforts.

With this in mind, one of the most effective ways to deal with an infringing website like Romwe is through legal action in China, either by way of administrative action or civil litigation.

Administrative action is where the rights holder goes to a local government agency, which operates as a quasi-judicial organization. The rights holder must complain to the government agency, and if the agency approves the complaint as valid, it will investigate. The government agency then has the power to issue an injunction to stop the infringement but does not have the power to award damages. This is generally a less attractive option for fashion rights holders as the administrative authorities’ power in relation to enforcing copyright infringement is not clear cut.

Civil litigation is similar to the court process in Europe and the U.S.: the parties submit their evidence and there is a trial. However, there is no disclosure procedure, which is usually where sales information and profits are disclosed to the claimant and used for the basis of calculating damages. And, not only is civil litigation in China time-consuming and expensive, but also China operates on a civil law system rather than a common law system, meaning that judges rule based on statute and do not follow precedent, making it difficult to determine how a court will rule in any given case.

Fashion brands looking to litigate in China would need to consider the fees of lawyers in their home jurisdiction, fees for their Chinese lawyers, and any related court fees, which are likely to run well into the thousands.

While many rights holders that go through this process might succeed in having infringing items removed from the company’s website, damages awarded are statutory damages, as opposed to than damages calculated on actual harm. These amounts are notoriously small in China, so pursuing this option does not make sense for many companies financially. Brands can also seek an injunction to prevent the sale of the infringing item, but being granted an injunction to stop the sale of a particular item does not effectively deter infringers from focusing on the same brand in subsequent seasons.

Therefore, brands seeking injunctions would be forced to continually repeat the same costly process. That time-consuming game of whack-a-mole? With this approach, it’s exceedingly expensive, too.

Thus, for many fashion brands, the cost involved with protecting their IP in China outweighs the reward. Commercially, many brands would rather focus their efforts on cleaning up websites such as Alibaba and Taobao, who are also more likely to comply to infringement notices. Sadly, until the Chinese legal system allows for easier enforcement of intellectual property rights, websites like Romwe will continue to shamelessly copy.

Rebecca McKenzie is a trainee lawyer with two years experience advising one of the UK’s biggest fashion brands on legal matters.