image: Vogue Australia

“Keeping Up With the Kardashians” has taken on a whole new meaning, “thanks to an influencer subculture of Kardashian lookalikes that’s emerged online,” wrote Women’s Wear Daily’s Rachel Strugatz recently. “This group of women, some now barely distinguishable from the real thing, have become influencers in their own right who boast anywhere from 500,000 to one million followers on Instagram.”

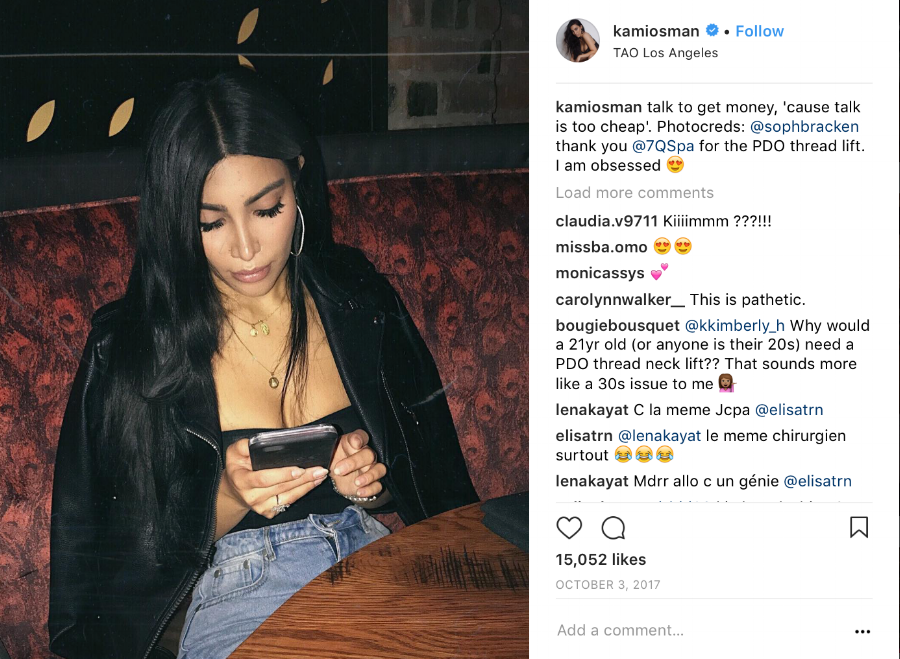

These follower-counts – such as Sonia Ali’s 743k followers or Kamilla Osman’s 530k – bring big deals. “A quick search on Instagram shows that these lookalikes have worked with brands from Estée Lauder Cos. Inc.-owned Glamglow in the Middle East and MAC Cosmetics in the United Arab Emirates to Iconic London, Gerard Cosmetics and Loving Tan,” according to Strugatz. And, in theory, these deals bring some complicated legal questions.

“By just merely looking [and dressing] like her you can get a job and be an influencer yourself. There’s a huge group of people who just look like Kim and some of them have over two, three million followers … People follow them because they look like her,” Dr. Simon Ourian, a Beverly Hills-based cosmetic dermatologist, told WWD.

Dr. Jason Diamond, a plastic surgeon linked to Kardashian after she documented her visit to his Beverly Hills office via Snapchat video, elaborated, saying that a huge part of Kardashian’s appeal is her looks. “Kim has an amazing face. That’s a big part of the reason why she is [as famous as she is].”

If this sentiment sounds even vaguely familiar, that may be because it is one of the argument’s that Kardashian’s legal team put forth in 2012 when she filed a lawsuit against Old Navy for using a lookalike model in one of its television advertisements.

Not the First Time

Yes, you may recall that in August 2012, Kim Kardashian filed a $20 million right of publicity lawsuit against the Gap, Inc.-owned retailer, alleging that by hiring a similar-looking brunette model named Melissa Molinaro to appear in a commercial for the brand, Old Navy had violated Kardashian’s right of publicity. According to Kardashian’s counsel, she “is immediately recognizable, and is known for her look and style,” and Old Navy knew exactly what it was doing by hiring a lookalike.

For those that are not up to speed on the right of publicity, it is a legal doctrine that gives individuals considerable exclusive control over the commercial use of their name, likeness and other identity attributes, as well as the right to prevent others from exploiting that value without permission. In order to make a case for a right of publicity violation, the use at issue must be “commercial” – i.e. an effort solely to sell a product or a service, which in the Old Navy case appears to be what the retailer was doing; using an individual that looked a lot like Kim Kardashian to promote its brand.

To be clear, that case (and any hypothetical claims at hand) centered on Old Navy’s alleged attempt to channel Kim K in its ad campaign in a commercial capacity, and thus, capitalize on her likeness without her authorization, and not on the legality of Molinari’s (or the influencers’) looks. The law cannot prevent people from looking like famous figures, regardless of whether it is a natural similarity or a cosmetic surgery-induced one. It can, however, prevent companies from making use of/profiting off of the likeness of famous figures in a commercial capacity, and those individuals from attempting to profit off their visual similarities to a famous person.

Kardashian and Old Navy managed to settle their differences, and thus, the case, before a judge could sound off on the matter, but it is a striking example of how Kardashian could react to this new market of lookalikes.

Vanna White, Jackie O

It is worth noting, after all, that her case against Old Navy was hardly the first of its kind. Vanna White, the ex-Wheel of Fortune hostess, for example, sued Samsung for using a robot in its advertisement that resembled her and was conveniently placed on a set similar to Wheel of Fortune. Siding with White, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit held that Samsung had, in fact, run afoul of the law by misappropriating White’s likeness for its own commercial gain.

Also, in an earlier case, Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis sued Christian Dior, arguing that the fashion house had violated New York’s right of publicity statute by using a look-alike in its print ads. According to Onassis’s complaint, Dior wanted to include her in an ad campaign, but since the brand knew that she would refuse to take part (she never allowed her name or image to be used to promote commercial products), they hired Barbara Reynolds, a celebrity impersonator of Onassis, instead.

Onassis argued that her right of publicity was being violated, and the court agreed, holding that Dior may not use Reynolds for her resemblance to Onassis in commercial advertisements, adding that “[n]o one has an inherent or constitutional right to pass himself off for what he is not.”

Such decisions very well might favor Kardashian should she decide to file suit against her lookalikes – or maybe more likely, the companies utilizing them, such as MAC and Glamglow – should it appear that they were acting in a capacity that aimed to profit from the lookalikes’ likeness to Kim K.

Confused?

There is an interesting aspect at play, here, that shares some important commonalities with the case that Kardashian previously filed against Old Navy. That case stemmed, at least in part, from the reality star’s fear for how the Old Navy commercial would affect her then-exclusive deal with Sears and also how it might serve to confuse consumers about the brands that she was – and maybe more importantly, was not – endorsing at the time.

As the Los Angeles Times wrote in 2012, “Kardashian claimed the ad might confuse consumers when it came to the products she does endorse, including a clothing line at Sears.”

This is a potential issue at hand because at least some of the value of Kim K’s name and likeness is tied to the fact that she only endorses certain brands. Sure, she will take a check to promote questionable weight-loss teas and hair supplements on Instagram, but chances are, Kardashian would not promote other brands’ makeup products or fragrances, as that would likely negatively affect her own KKW collections.

It is worth noting that many of the brands that WWD notes as tapping Kim K lookalike influencers – such as Ali and Osman – are cosmetic and other beauty brands, thereby, potentially creating a conflict for the real Kim K. Should consumers be confused as to the star’s real endorsement deals, which, in turn, give rise to an additional cause of action, unfair competition; and should the appearance of Kim K clones in ad campaigns or sponsored Instagram posts give rise to a potential false and misleading impression that Kim, herself, is endorsing a product when she is not.

In short: This is a complicated one that should be approached with caution, dear, Kim K lookalikes.