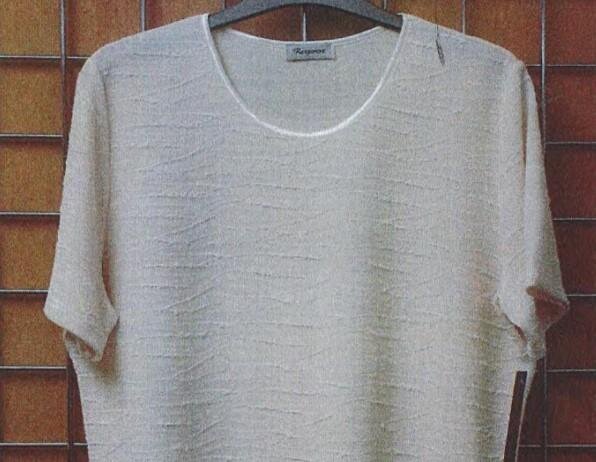

At the center of a recent decision that stands to significantly impact the protections afforded to fashion brands in the United Kingdom is something as simple as knitted tops, ones that Edinburgh Woollen Mill (“EWM”) had been selling until its third-party manufacturer upped its prices, a move that caused the two companies to cut ties. Out of a supplier and in need of more of these hot-selling woven fabric tops, EWM – a British apparel chain that maintains a brick-and-mortar network of some 400 stores – took a sample of the fabric from its former supplier Response Clothing and shopped it around in an attempt to find another manufacturer to create similar garments sans the steep markup.

EWM’s attempt to cut costs worked. It would not be long before the nearly 75-year old had a steady supply of the shirts it needed, ones created with a nearly-identical jacquard-woven textile complete with Response’s original “wave arrangement,” all without having to pay the increased price that Response Clothing had been angling to impose. It similarly would not be long before that seemingly too good to be true deal landed EWM on the receiving end of a lawsuit, with Response Clothing claiming copyright infringement.

In the complaint that it filed after getting wind of EWM’s new wares, Response Clothing accused EWM of hijacking its jacquard fabric for the nearly-identical tops it had begun offering, and argued that the fabric, itself, is subject to copyright protection, thereby, putting EWM on the hook for copyright infringement. As of early this month, Response Clothing was handed a striking victory when the Intellectual Property and Enterprise Court (“IPEC”) determined that the design of the fabric is a “work of artistic craftsmanship,” and thus, meets the requisite standard in order to be protected by copyright law.

Siding with Response, IPEC judge HHJ Richard Hacon held that while the fabric design is not an example of a graphic work (a category of works protected by copyright law in the UK), it is nonetheless protected by copyright law as a “work of artistic craftsmanship,” as it meets the relevant standard of being “the creation of the fabric required skillful workmanship, and artistic in the sense that it was produced with creative ability that produced aesthetic appeal.” The commercial success of Response’s fabric – which EMW sold for three consecutive years – is evidence of such “aesthetic appeal,” according to the court.

Elaborating on the bounds of what may qualify as a “work of artistic craftsmanship,” HHJ Hacon held that it is possible for a work of artistic craftsmanship “to be made using a machine; aesthetic appeal can be of a nature which causes the work to appeal to potential customers; and a work is not precluded from being a work of artistic craftmanship solely because multiple copies of it are subsequently made and marketed.”

Hardly a throwaway case, the court’s decision “stands to enable fashion designers to use copyright protection on a much wider basis to prevent copying of their designs,” according to Osbourne Clarke’s Hannah McCarthy. This is particularly relevant in light of the fact that “UK copyright law has historically been of limited use for fashion designers seeking to protect their designs.”

McCarthy states that “for copyright protection to apply in the UK, a work must fall within a pre-existing category outlined in the Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988, which includes works of artistic craftsmanship as one category,” noting that fashion designs “do not fall neatly into any of these categories” and that no shortage of previous attempts by brands “to assert that articles of clothing were works of artistic craftsmanship were rebutted by the courts.”

“This judgement is likely to lead other fashion designers to argue that certain types of garments (not just jacquard type fabrics)” fall within the bounds of copyright protection as works of artistic craftsmanship,” McCarthy further asserts, thereby, enabling them to rely on more than design law, which “has limitations in terms of duration.”