From “vintage” Chanel jewelry and monogramed Fendi box bags to Gucci kitten heels and Gold Courchevel Birkin bags, Wyld Blue boasts a lineup of big-name luxury brands in furtherance of its quest to “celebrate genuine, rare vintage and pre-owned designer pieces.” The buzzy boutique – which is located in the summer hotspot of Montauk, New York – swears by its relationships with “the industry’s most reputable suppliers.” Yet, despite such ties, it is coming under fire for allegedly passing off counterfeit luxury goods as the real thing, and ultimately, landing itself at the center of an Instagram-centric legal scandal in the process.

The budding legal scuffle involving Wyld Blue got its start late last month when WePhotoshoppedWhat2, the Instagram watchdog account dedicated exclusively to calling out influencer Danielle Bernstein, says that it got a tip. “Got a [direct message] from a girl who bought Chanel earrings from [Wyld Blue],” the operator of the account stated in a post on the Facebook-owned photo-sharing platform on August 27. “Turns out, the $500 earrings were fake.”

In response, Wyld Blue released a statement by way of an Instagram story post, confirming that one of its suppliers “admitted to us that she had sold use fake Chanel Huggie earrings.” The company said that it “refunded, recall, and apologized to all involved,” while assuring its followers that “all items currently in our store have proof of purchase cards, have come from reputable suppliers,” and are now subject to “third party authentication.”

Undeterred, WePhotoshoppedWhat2 doubled down on Wyld Blue and its founder Sasha Benz (and its recurring target Bernstein for promoting the same, allegedly counterfeit Chanel earrings). Since its initial post, WePhotoshoppedWhat2 has been busy sharing screenshots of messages from individuals who allegedly purchased fake products from Wyld Blue, and highlighting Wyld Blue’s offering up of “FAKE Cartier bracelets and ‘INSPIRED’ Chanel hair ties (for $100??!).” Meanwhile, other social media users, including writer Sophie Ross, who has been documenting the drama on her timeline, have been quick to chime in on the allegedly inauthentic nature of Wyld Blue products.

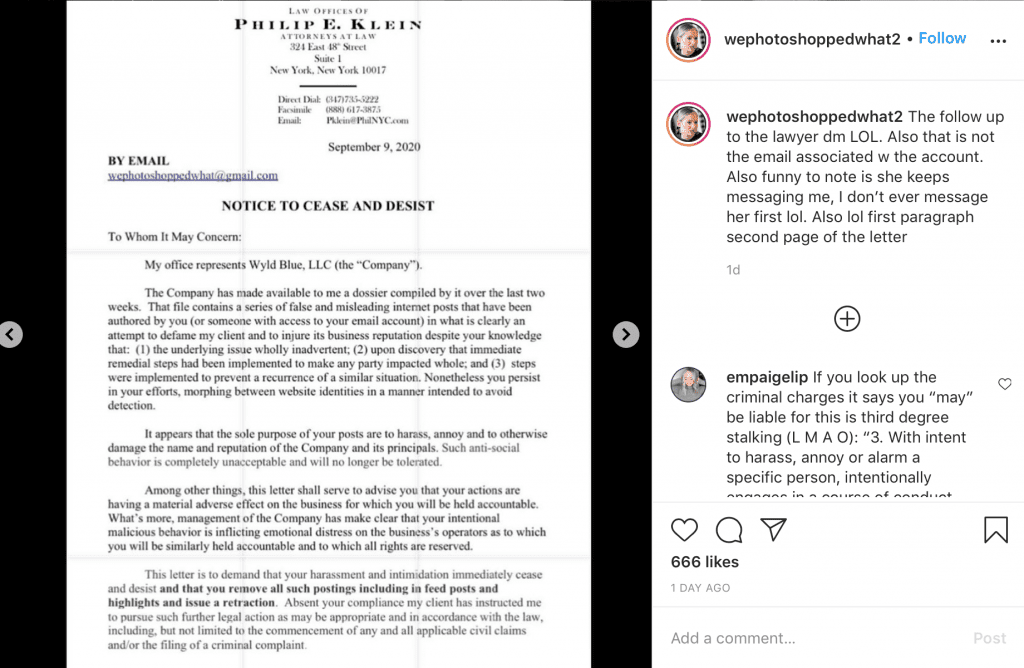

However, the most striking of the WePhotoshoppedWhat2’s content as of late is not the side-by-side images of real and fake Chanel packaging or allegations of counterfeit Dior bracelets. It is a cease and desist letter that counsel for Wyld Blue, LLC allegedly sent to the account’s operator via email. In a correspondence dated September 9, Wyld Blue’s lawyer accuses the anonymously-run WePhotoshoppedWhat2 of publishing “a series of false and misleading internet posts … in what is clearly an attempt to defame my client and to injure its business reputation.”

“It appears that the sole purpose of your posts [is] to harass, annoy and to otherwise damage the name and reputation of [Wyld Blue] and its principals,” the letter states, asserting that “such anti-social behavior is completely unacceptable and will no longer be tolerated.”

The letter goes on to advise the operator (or operators) of the WePhotoshoppedWhat2 account that “your actions are having a material adverse effect on the [Wyld Blue] business for which you will be held accountable,” and that “your intentional malicious behavior is inflicting emotional distress on the business’s operators.” In addition to putting the account holder on notice, the letter demands that such alleged “harassment and intimidation immediately cease and desist and that you remove all such postings in feed posts and highlights, and issue a retraction.”

“Absent your compliance,” Wyld Blue’s counsel states that “my client has informed me to pursue further legal action.”

Interestingly, while the letter certainly eludes to a defamation cause of action, namely when it asserts that WePhotoshoppedWhat2’s posts are aimed at “damaging the name and reputation of” Wyld Blue, it does not actually cite legal action on the basis of libel (i.e., defamation expressed in writing). Instead, the letter claims that the Instagram account’s behavior “may be a violation” of various sections of the New York State Penal Law, namely, various degrees of harassment, aggravated harassment, criminal nuisance, stalking, coercion, conspiracy, and menacing.

In terms of the identity of the individual(s) behind the WePhotoshoppedWhat2 account, that is unclear. In a direct message that Benz appears to have sent to WePhotoshoppedWhat2 on Instagram, she cites her counsel, who requests the name and address of the account operator in connection with claims of “defamation, false light, and other tortious claims and damages.”

Seemingly still without the identity of the account operator, Wyld Blue’s counsel asserts in the subsequently-issued cease and desist email, “Rest assured that we will find you. It may take time, but your identity will be discovered. Trained operators, expert in hurdling proxy walls and VPNs, are being enlisted to discover your identity … and it will be discovered, the cost of which will be passed along to you should your behavior persist.”

In the wake of such interactions, WePhotoshoppedWhat2 has continued to document the budding legal drama, posting a screenshot of what appears to be another Instagram direct message from Benz sharing the cease and desist letter – which WePhotoshoppedWhat2 has since revealed was sent to an email address that is not associated with its account – and “checking to see that you received the correspondence from my attorney.”

Call-Out Litigation

Not the first legal squabble to erupt from the rise of digital cancel culture, advertising industry watchdog account Diet Madison Avenue, for example, landed on the receiving end of a defamation lawsuit in 2018.

Ralph Watson, the former chief creative officer for Crispin Porter & Bogusky, filed suit against Diet Madison Avenue and a handful of “Does” (i.e., a person that cannot be identified by the plaintiff before a lawsuit is commenced; in this case, the account operators) in a California state court, alleging that they erroneously labeled him an “unrepentant serial predator,” who “targeted and groomed women,” and encouraged his advertising agency employer to fire him without “provid[ing] even a scintilla of evidence or proof supporting any allegations of harassment or other ‘predatory’ misconduct.’”

The case – which was followed up by two subsequent filings, including one in a New York federal court – was expected to “have implications for how people behave online and their belief that what they do or post is truly anonymous,” as CNBC put it last year, particularly since Watson obtained a limited court order in California to issue subpoenas to Facebook, Instagram and Google to provide identifying information about the individuals behind the account and certain Gmail accounts.

Matthew Tokson, associate professor of law at the University of Utah S.J. Quinney College of Law, told CNBC that the outcome will be one of watch for: “The fact that people are functionally anonymous a lot of times produces good things since people can speak freely, but also produces a lot of bad stuff, like online abuse and the spread of fake news.” Put simply, this will prove to be a balancing act for courts given that “we don’t want people to be able to spread lies on the internet and never be de-anonymized, but we also don’t want to deter people from saying truthful things.”

Watson’s case in New York is still underway.

As for sending cease and desist letters via social media, Wyld Blue is not the first to do so. As Daniel Doft stated in his 2016 article, “Facebook, Twitter, and the Wild West of IP Enforcement on Social Media: Weighing the Merits of a Uniform Dispute Resolution Policy,” because “social media infringers can hide behind their IP address, making it difficult for an owner to ascertain their private contact information, infringed parties have started sending cease-and-desist letters through a private or public message on the social media website itself.” In 2008, for example, he notes that “Burger King served a cease-and-desist letter through Twitter to theowner of the account “@whoppervirgins.” The outcome of Burger King cease and desist (Twitter) letter remains unknown.