The rise of Golden Goose from budding young sneaker maker to increasingly in-demand global brand has brought with it a whole slew of copycats aiming to get in on the appeal of its Superstar. A quick survey of the market reveals a growing number of Steve Madden and Aldo iterations to renditions from digitally-native fast fashion entities, such as Shein and Fashion Nova, all which have something in common: the prominently placed star on the side of each of the individual shoes, an element that has become the identifying feature that alerts consumers that an otherwise run-of-the-mill pair of distressed leather sneakers is the product of the Francesca Rinaldo and Alessandro Gallo-founded brand, Golden Goose.

The surge in low-cost lookalikes of Golden Goose’s $400-plus Superstar sneakers comes as the Venice, Italy-headquartered company has been in the midst of ownership changes and noteworthy expansion efforts, with quite a bit of the latter coming under the watch of former Supreme-owner Carlyle Group, which acquired the privately-held Golden Goose in 2017 from a group of Ergon Capital Partners-led investors. During its time under Carlyle’s umbrella, Golden Goose “expanded from seven stores to 90,” MarketWatch asserted last year, and “increased its number of employees from 100 to 300 people.” Also on the rise? Annual revenues, which were up from roughly €50 million in 2014 to nearly €200 million in 2018, per Reuters, with as much as 80 percent of those sales coming from outside of the 21-year-old brand’s native Italy.

In the most recent turn of events, private equity giant Permira snapped up Golden Goose from Carlyle in February 2020 in a deal that valued the company at $1.4 billion – or nearly 15 times the company’s earnings (a similar multiple as VF Corp. paid when it acquired streetwear “it” brand Supreme for $2.1 billion in November 2020), and all the while, sales are projected to continue to grow, as consumers shell out for what The Cut called “a kind of lowbrow luxury that, clearly, people want today.” (Or what Gen-Z TikTok-ers have called Cheugy.)

It would not be fair to assume that none of Golden Goose’s customers are buying its sneakers because of the aesthetic of the shoes; as the Wall Street Journal stated in a March 2016 article, titled, “The Cult of Golden Goose,” it is “their synthesis of West Coast skater cool and Venetian craftsmanship … the handmade, distressed touch [of the sneakers] that makes them unique, and for kicks fans, individuality is everything.” At the same time, what is probably more realistically drawing in a larger pool of eager buyers – and what allows Golden Goose to charge hundreds of dollars for its “status symbol” footwear – is the aura of the buzzy Golden Goose brand, itself, which is translated to consumers by way of its trademarks, namely, its name and its arguably-source-identifying star.

Need proof that the star is the takeaway element (even if the shoes are made by hand)? There is nary an article about the luxury sneaker-maker and its burgeoning success without a mention of that very emblem.

With that in mind and given the value tied to brands’ trademarks, it is no surprise that as part of the larger growth endeavors that have been underway, Golden Goose – whose business has expanded to clothing and accessories, but is still largely generated by the eye-watering number of pairs of expensive Superstar sneakers that it sells each year – has been on a quest to expand its portfolio of trademark registrations across the globe. This move aims to add tools to Golden Goose’s enforcement arsenal (which is particularly relevant given the rise in copycats) and to add significant value to the company, itself. The exercise in amassing formalized protections has coincided with the roll out of new Golden Goose stores, its hiring of hundreds of new employees, and its expansion into ready-to-wear, and has seen the brand acquire star-centric and word mark registrations from trademark offices in various countries.

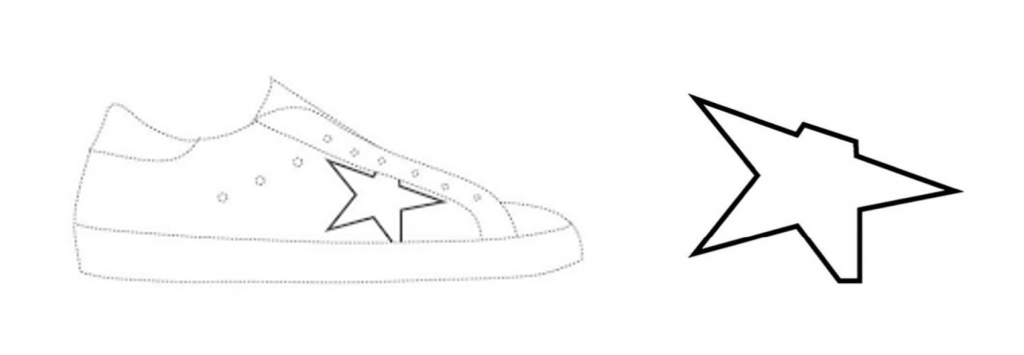

Its global registration-seeking efforts have not come with a bit of pushback along the way, though. Back in August 2017, for instance, Golden Goose filed a trademark application for registration with the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (“USPTO”) for a mark consisting of “a tilted five-pointed star with the top point cut off and the tip of the lower right point cut off” (pictured above right) for use on footwear and leather goods.

Just over a year after Golden Goose filed its application in the U.S., Skechers called foul. By way of an opposition proceeding, the Southern California-based footwear brand sought to block the registration of Golden Goose’s signature star mark on the basis that the “mark is purely ornamental or, alternatively, is merely ornamental without acquired distinctiveness and therefore, does not function as a trademark.” Beyond that, Skechers argued that “due to unpoliced, or unsuccessfully policed, third-party uses of similar marks” to Golden Goose’s star, “the public cannot and does not identify [Golden Goose] as the single source of the goods claimed in the application,” namely, footwear and leather goods, another reason why the application should be tossed out.

Fast forward a few years and the opposition battle between Golden Goose and Skechers – the latter of which is offering up a number of Golden Goose-esque star-adorned styles of sneakers of its own – is still underway. (The brand has since filed applications for registration for the same mark in Mexico, New Zealand, Spain, Switzerland, France, Italy, and Canada, among other countries, and with the World Intellectual Property Organization, for use on garments and footwear, with quite a bit of success.)

In the meantime, Golden Goose has also filed additional applications for registration for variations on its signature star design, which are pending before the USPTO, as well as an application for the specific placement of its star (pictured above left). The mark consists of “a design of a five-pointed star placed on the side of a shoe,” noting that “the majority of the top point of the star is cut off where the shoe upper meets the throat of the shoe, [and] the bottom tip of the star is cut off where the shoe upper meets the sole.” Given that the latter mark – which Golden Goose says it first began using in 2007 – is more specific than the general use of its stylized star on garments and footwear, and thus, Golden Goose’s rights in it are more limited, it might face less pushback from competitors like Skechers. It also has over a decade of sales of the shoes bearing the trademark to point to, paired with seemingly countless celebrity fans, unsolicited media attention, and presumably, sizable advertising expenditures in furtherance of an argument that consumers associate the mark with a single source.

An open-and-shut matter without oppositions from rival footwear markers is not a guarantee even for that mark, though. As indicated by the number of star-adorned footwear popping up in other companies’ offerings, it seems that almost everyone wants in on the enduring appeal of the Golden Goose brand and its sneakers.