A settlement agreement has not been enough to keep at least one of Boohoo Group, PLC’s brands from shamelessly copying an array of Dr. Martens designs, the cult boot brand’s parent company claims in a new lawsuit. Despite entering into a confidential settlement agreement with Pretty Little Thing in June 2017 in which the British fast fashion brand agreed to cease its infringement of Dr. Martens’ legally-protected footwear designs (in order to avoid litigation), and regardless of Boohoo and Nasty Gal being put on notice of their alleged infringement of Dr. Martens shoes in 2017 by the brand, AirWair International argues that all three fast fashion companies have “willfully continued [such] infringement to this day.”

According to the multi-million trademark infringement and dilution, and breach of contract suit that Dr. Martens’ parent company AirWair filed in a federal court in Northern California last week, Boohoo, Nasty Gal and Pretty Little Thing have been infringing Dr. Martens’ trade dress-protected footwear since “as early as 2016 and have continuously infringed [these legal rights] since then” by way of a revolving supply of lookalike shoes.

AirWair alleges that it has been using the various “distinctive Dr. Martens trade dress” – a subset of trademark law that provides protection for the overall image of a product, such as the color, shape, size, and/or configuration, as long as the design has the same source-identifying function as a traditional trademark, such as a logo or word mark – for its “iconic boots and shoes since 1960 around the world,” leading to consumers to associate the designs with the Dr. Martens brand.

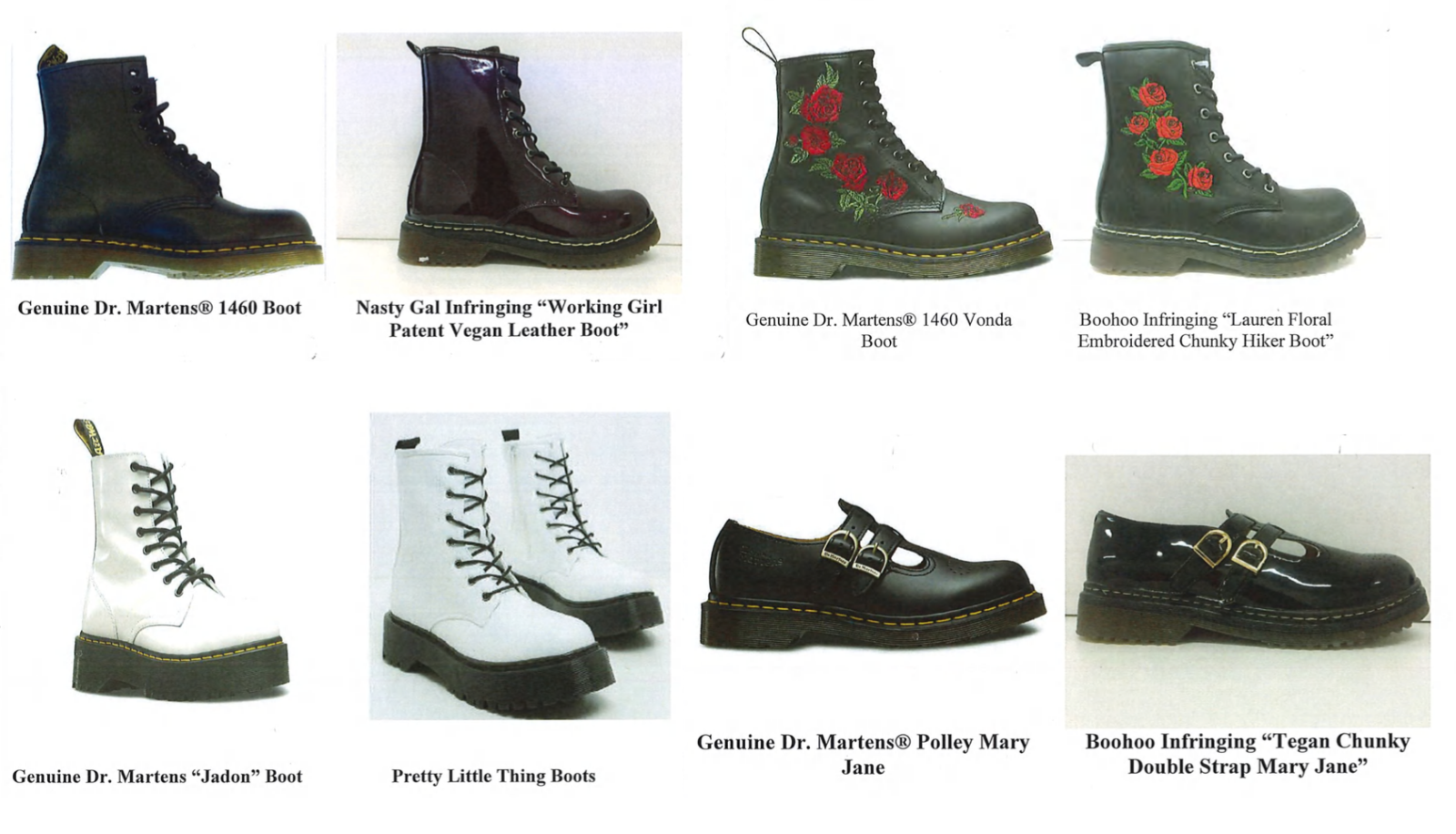

With that in mind, the defendants have taken to “intentionally copying [its] trade dress” – including that of its 1460, Vonda and Jadon boots, as well as its Polley Mary Jane – “in order to capitalize on the reputation and fame of the Dr. Martens brand.”

While the fast fashion business (and to some extent, even the high fashion business) is largely based upon the replication of already-existing designs, this is not a run-of-the-mill copycat case, AirWair alleges. Instead, the Wollaston, United Kingdom-based company claims that “this is an ‘exceptional case’ of infringement … because the defendants knowingly and intentionally used the Dr. Martens trade dress and intentionally sold copied footwear with the intent to confuse consumers.”

images via complaint

images via complaint

Not only does such copying give rise to trade dress infringement, false designation of origin, and unfair competition, AirWair claims that the defendants are engaging in dilution of its distinctive and source-identifying designs in violation of California state law. By selling shoes that make use of its exact designs, such as the design of its 1460 boots, AirWair claims that Pretty Little Thing, Boohoo and Nasty Gal are “lessening the capacity of the trade dress to identify and distinguish [Dr. Martens’] products” from the products of others.

In other words, by making and selling shoes that look exactly like Dr. Martens 1460 boots – i.e., shoes that consist of a “two-toned grooved sole edge, the distinctive DMS sole pattern, yellow stitching in the welt area of the sole, and a black fabric heel loop” – Boohoo and co. are making it less likely that consumers will continue to associate the elements of the 1460 boots – when taken together – as a design coming exclusively from a single source.

AirWair is seeking preliminary and permanent injunctive relief barring the defendants from making and selling any infringing footwear. It has asked the court to order the defendants to produce “all materials and products bearing [its] images and representations [and] any of the trade dress features” for destruction, and to provide the court with an accounting of all profits made in connection with its alleged infringement of the trade dress, including a disclosure of “the number of pairs of infringing footwear sold in the United States, internationally, and the gross revenue derived from the sale of the footwear.”

As for monetary damages, Airwair is seeking actual damages and profits, or an award of statutory damages of no more than $1,000,000 per counterfeit mark per type of services and/or goods or offered for sale by defendants – which could quickly amount to several millions given the defendants’ expansive portfolio of allegedly infringing shoes.

This case is just allegedly “exceptional” due to the “intentional” nature of the infringement at hand, it is striking as most fast fashion copying goes unlitigated due largely to something of a lack of readily-available protections for many garments and accessories in the U.S. While design patents protect useful things, such as clothing, and are relatively easy to get, they involve a more time-consuming and expensive process than say, copyright law, which comes with its own downsides, such as the often hard-to-achieve separability requirement. (Given the Supreme Court’s ruling in Star Athletica v. Varsity Brands, fashion brands may have a greater ability to claim a bit more protection under the umbrella of copyright law).

In terms of trade dress, which is what AirWair is basing the bulk of its claims on here (and a type of protection that often extends to footwear), in order to claim such protection for the appearance of a product, that design must maintain the necessary level of “secondary meaning,” meaning that consumers link the appearance of the product, itself, with its source, which can be expensive and time-consuming to establish.

As such, most garments and accessories – save for long-standing staple products, such as Dr. Martens 1460 boots, or those of deep-pocketed brands, such as Louis Vuitton and Gucci – go relatively unprotected, making copying more a necessary evil than a highly-litigated issue.

*The case is AirWair International Ltd. v. Boohoo Group, PLC et al, 5:19-cv-04078 (N.D. Cal.)