Luxury brands are notoriously controlling of their image and the factors that go into creating and maintaining it, which is precisely why in the face of the swiftly growing resale market, “investors should watch for signs that brands are considering their own resale services,” the Wall Street Journal’s Carol Ryan wrote on the heels of digitally-native luxury consignment company The RealReal’s stock market debut on Friday. Launching their own resale services would give brands “greater control over prices [and availability] in the secondary market and boost their sustainability credentials with millennial shoppers.”

The potential that luxury brands will move to establish – or acquire – their own resale operations is not without premise. Audemars Piguet, “whose Swiss-made watches sell for over $50,000, recently revealed plans to launch a secondhand business,” per Ms. Ryan, while Richemont – the Swiss conglomerate that owns Baume & Mercier, Cartier, IWC Schaffhausen, Officine Panerai, and Piaget, among other watch brands and fashion companies – snapped up second-hand watch-selling platform Watchfinder last year.

Still yet, just last month upscale outdoors brand Arc’teryx announced the launch of Rock Solid, which will see it buy back used Arc’teryx products from consumers. “Arc’teryx will then refurbish these items so that they are in like-new condition, and sell them on a special section of the Arc’teryx website at prices that are about a third less than they would be new,” according to Fast Co. The new program is a sustainability-centric attempt by the brand to “extend the value of worn gear” more than it is a ploy to control the distribution, but it is a compelling model, nonetheless, and a indication of where the industry is going on a broader scale.

Meanwhile, carmakers, “like BMW and Jaguar, [which, although not a perfect parallel], certify and warranty used cars for the resale market,” Ryan notes.

Aside from the growing number of examples of brands employing resale efforts of their own, the exact foundation upon which luxury largely depends – exclusivity, high prices, meticulously-crafted marketing, valuable intellectual property, and careful governance in terms of distribution – is influx given the mainstreaming of resale, thereby, making control the very luxury that luxury brands are most ardently seeking in order to maintain their positions in the upper echelon of the industry (and thus, demand top-dollar for their offerings).

If brands want to maintain some semblance of command over the prices for which their pre-owned products are selling, for instance, or the continue to attempt to uphold the image of exclusivity (which is one of the central aims in the marketing strategy in the luxury segment), playing a larger role in resale operations will be critical.

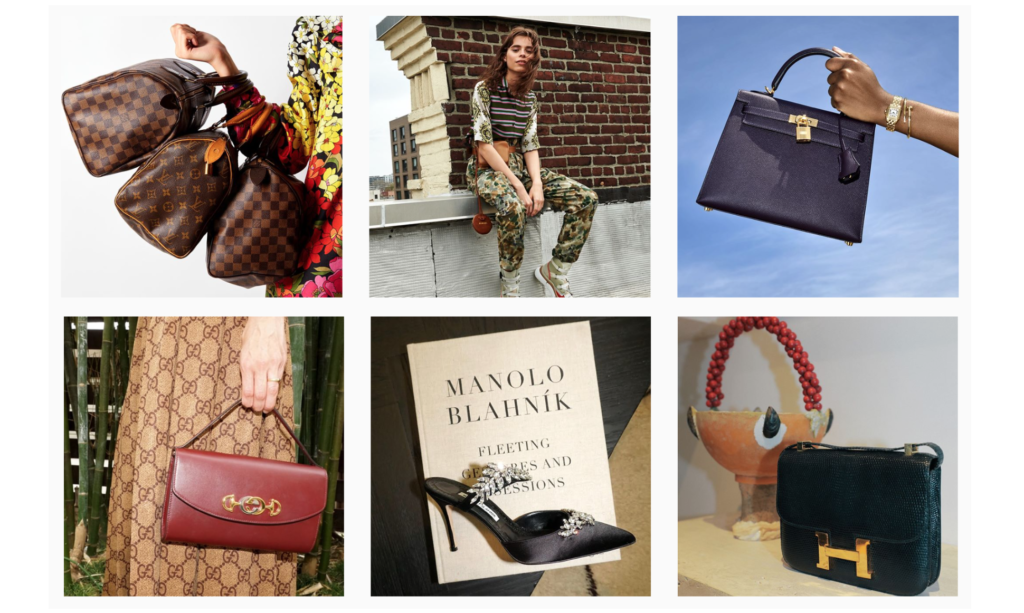

For Ryan, this primarily takes the form of brands establishing resale efforts of their own, which could prove a detriment to the likes of The RealReal. Even if luxury brands begin “offering to take back [their] highest-margin items, such as Hermès Birkin handbags or expensive watches,” in order to ensure that their most iconic products are carefully controlled, she says, that “would take an important source of revenue from The RealReal [and other resellers] and make turning a profit even harder for the heavily money-losing business.” Those losses take the form of “$52.3 million, $75.8 million and $23.2 million in 2017, 2018 and the three months ended March 31, 2019, respectively, The RealReal stated in its IPO filing, and “an accumulated deficit of $281.0 million” as of March 31, 2019.

Increased oversight by brands is not limited to in-house operations, though; it could take the form of partnering with some of the market’s biggest players, including The RealReal.

For brands like Chanel, in particular, which has been notoriously litigious when it comes to resale market participants, this could – at least in theory – alleviate some of its heavily-voiced concerns about the authenticity of the bags at play. More than that, it could address some of the concerns that Chanel (and its peers) are not declaring: a growing lack of control over the marketing, merchandising, and pricing of their products.

While such partnerships seem like a win for all parties involved – from consumers (as such partnerships would lead to increases in collaboration in terms of authentication) to brands and resellers, luxury brands have been slow to adapt. Yet, as resellers – such as The RealReal and StockX, for instance – continue to break the $1 billion valuation mark, and the resale market as a whole continues to sky-rocket, including for luxury goods, brands will likely begin to change their tune.