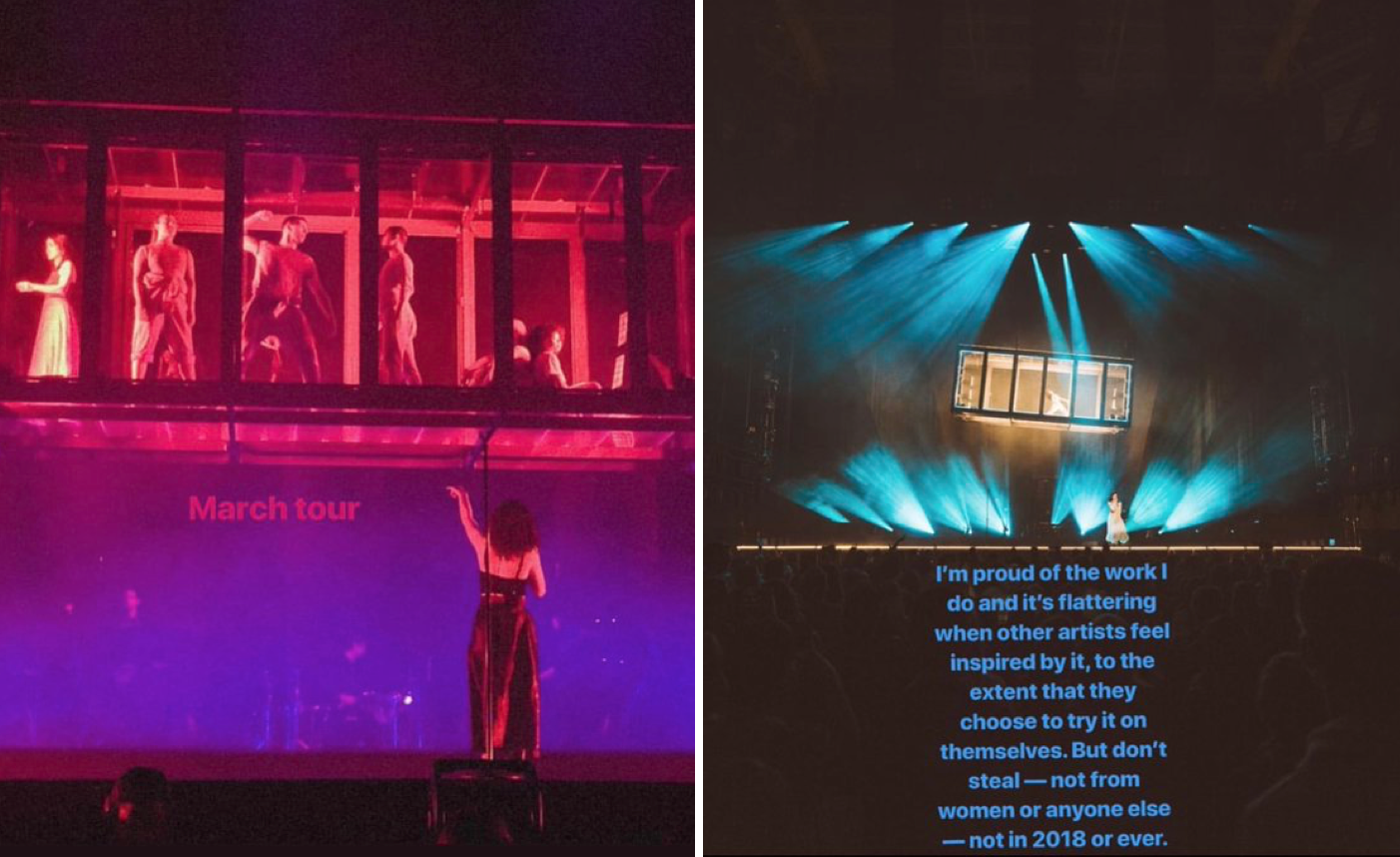

Lorde is calling out Kanye for copying. On Monday, the New Zealand-born musician posted images on Instagram from Kanye West and Kid Cudi’s recent performance at the Camp Flog Gnaw festival in Los Angeles, pointing to the similarity of the duo’s set design – they performed inside a transparent rectangle-shaped box (pictured above), accented with florescent lights at certain points, flames at others, and suspended above the stage throughout – and one that she utilized for her 2017 Coachella festival performance and her subsequent Melodrama world tour.

In connection with the images, Lorde stated, “I’m proud of the work I do and it’s flattering when other artists feel inspired by it, to the extent that they choose to try it on themselves. But don’t steal – not from women or anyone else – not in 2018 or ever.”

Tuesday brought an interesting twist and important move of context-adding when Es Devlin, the designer behind Lorde’s set and a longtime Kanye West stage collaborator, shared a trio of images on Instagram depicting another set she has designed previously. It was for the English National Opera’s production of CARMEN in 2007, ten years prior Lorde’s Coachella performance. The National Opera’s set included yet another rectangular cube inside of which musicians performed.

In essence, Devlin – who has said that she did not create the stage design for West and Kid Cudi’s recent show – set the record straight on Lorde’s call of foul.

London-based Devlin’s resume is long and jam-packed with work on Kanye West’s “Touch the Sky” tour (among others), West’s tour with Jay-Z called “Watch the Throne,” Lady Gaga’s “Monster Ball,” the Pet Shop Boys’ “Electric” world tour, Beyoncé’s “Formation” world tour, Miley Cyrus’s “Bangerz” tour, and U2’s Innocence+Experience tour. There are big-time theater titles in the mix, too, along with runway shows for Nicolas Ghesquière’s Louis Vuitton and Chanel.

Lorde’s Melodrama tour set

Lorde’s Melodrama tour set

No small number of Devlin’s sets make use of L.E.D. lights, “kinetic sculptures meshed with light and film,” and in more instance than one, over-sized transparent cubes inside of which actors and/or musicians, depending on the project, could be found. Beyond Lorde’s set and the one for CARMEN, Devlin has shown similar cube-like designs for the Sam Mendes-directed The Lehman Trilogy, which debuted in London and is destined for New York’s Park Avenue Armory for a limited season in March.

So, what is at play here legally speaking: The sculptural and architectural aspects of original stage and set designs are protected by copyright law. In fact, in October 1997, in refusing to dismiss a case that centered on “stolen stage designs,” Judge Kenneth L. Ryskamp of the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of Florida marked the first time that a U.S. federal court recognized a copyright certificate for a theatrical scenic design and issued a favorable ruling, which deemed stage designs to be copyrightable.

As for whether Lorde (assuming that she is, in fact, the copyright holder for the stage designs she commissioned from Devlin) has anything more merited than a Instagram claim (where the bar for calling “copy!” is immeasurably lower than in a court of law), it is up for debate.

On one hand, the giant, suspended cube – paired with any creative lighting design – might be categorized as a visual work of art, and the original elements of it protected by copyright law.

On the other hand, though, there is a chance that, from a copyright perspective, there is not much to protect here. As E News and a few other sites noted in connection with their coverage of the musicians’ spat, “Devlin told fans the idea of a floating glass box ‘is not in any way new.’”

The legally minded amongst us will know that copyright law does not protect ideas … and might argue that a glass box stage design suspended in the air is more an idea (which copyright law does not protect) than a legally-protectable thing.

Instead of protecting ideas, copyright law provides protection for the original, tangible expressions of ideas (and even then, still does not protect the underlying ideas of those expressions). Practically speaking, this means that one can freely copy another’s idea without the threat of liability because the copyright holder owns only the expression of the idea, and thus, allows for many different tangible expressions of the same idea to exist.

Apply that principle to the situation at hand and that very well might mean that save for any added creative elements, such as lighting design or specific sculptural elements of the cube itself, all we have are transparent cubes, a clear case of inspiration (or even imitation), and one more copying call-out that would not survive in court.