A $2 million-plus lawsuit accusing EDUN and LVMH Moet Hennessy Louis Vuitton of racial discrimination and retaliation has landed before the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of New York. The case got its start early this year when former EDUN-Americas sales associate Indigo Brunton filed suit against the now-defunct Ali Hewson and Bono-founded fashion brand and its former minority stakeholder LVMH in a New York state court alleging that during her several-month tenure with the made-in-Africa fashion brand, she faced “race discrimination that resulted, ultimately, in her constructive termination from [EDUN].”

In her January 4 complaint, Brunton, a Black female, asserts that she started working at EDUN’s retail store in January 2018, and almost from the outset was subjected to the “constant … racially offensive and derogatory comments” that EDUN sales advisor Angele Laroq made “to [her], about [her], about customers, and about Black people in general.” Brunton claims that much to her “shock and disgust,” Laroq – who held herself out as Brunton’s supervisor (but was later revealed to be a fellow sales associate) – “repeatedly referenced the N word, referred to Black people as ‘Ghetto,’ accused Black people of ‘trying to act Afro-centric,’ criticized Black people stereotypically, and perpetuated Black stereotypes.”

Despite advising Laroq that “she was uncomfortable with the racially hostile atmosphere and ask[ing] her to stop making racially charged comments,” Brunton claims that Laroq “continued to harass [her] by subjecting her to a racially hostile work environment,” which prompted Brunton to report the alleged discrimination to EDUN manager Sabrina Realas “when she came to the store on February 9, 2018.” While Realas thanked Brunton for confiding in her about Laroq’s behavior and offering to do “anything I can” to help, Brunton alleges that EDUN “failed to implement an investigation” and “did nothing in response to [her] reports of race discrimination,” causing the “race based hostile work environment perpetuated by Laroq [to] continue unabated.”

“Surprised at having not received any follow up to her complaints of discrimination,” Brunton asserts that she raised the issue again in a February 20, 2018 performance review with Realas and EDUN CEO Julian Labat, the latter of whom is named as a defendant. During that performance review (in which she claims that she was informed that “she had brought the store to a ‘new level’ and that there was a noticeable increase in sales”), Brunton alleges that Realas and Labat advised her that “avoiding conversations with Laroq would ‘allow their professional relationship to become amicable.’” More than that, Brunton alleges that Labat told her that “if she did not ‘make things work’ then they would have to ‘discuss’ her leaving [EDUN].”

Having left the performance review without a solution, Brunton claims that several days later, she “again reported the retaliation and discrimination to Realas and asked for assistance in dealing with the uncomfortable and hostile work environment.” Realas told Brunton on March 5 that the company was “reviewing [the matter] very closely and ask that [you] give us some time to address it accordingly,” per Brunton, when claims that Labat echoed this in an email a few days later, telling her that because EDUN did not “have an internal HR department, the investigation is going to be managed by Rachel Cohen, HR Manager at Fendi Americas.”

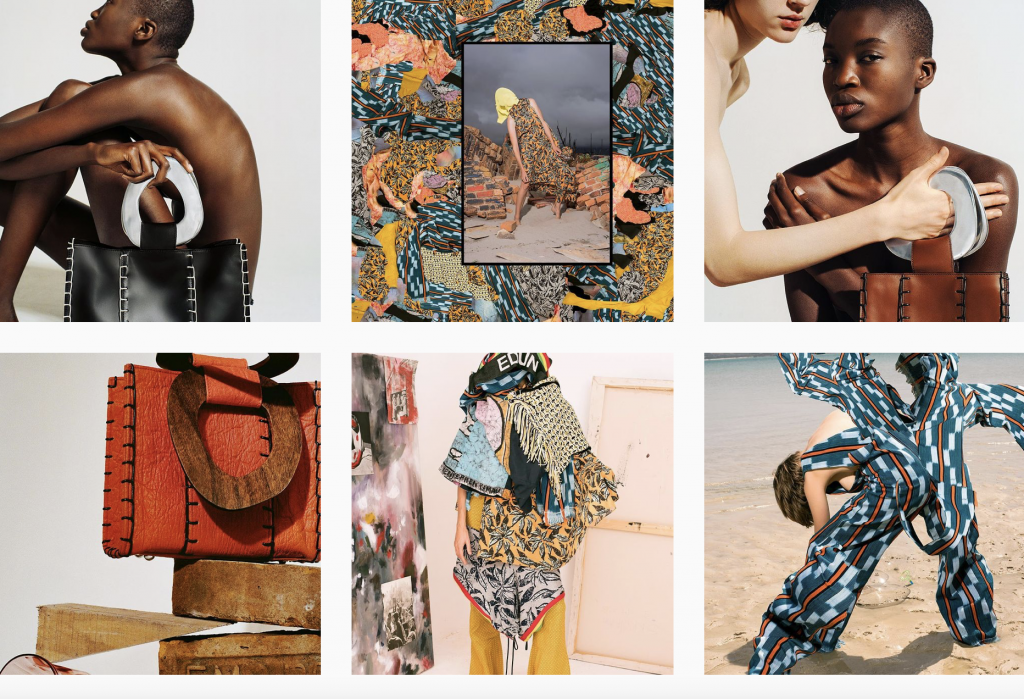

Brunton claims that while she “was hopeful that the matter would be addressed and resolved,” she was also “concerned about Labat, as she had heard from other employees that he regularly made racially hostile comments such as ‘Black models can’t sell clothes,’ that he had refused to respond to complaints that models were being sexually harassed by the defendants’ financial controller, and that he had made racist comments that caused other employees to quit.”

After meeting with Cohen in mid-March to discuss her complaint, Brunton says that she met with Cohen and Labat a week later, at which point Labat revealed “that they had worked with an attorney from LVMH, and the investigation was ‘complete.’” He alerted Brunton that they “found no incidents of racism or harassment,” and allegedly “explained in a demeaning and clearly annoyed tone that [Brunton] was ‘confused about things’ and informed her that ‘the situation [between herself and Laroq] was caused by a lack of clarity.’” Brunton claims that she was “dumbfounded” by Labat’s remarks and by the fact that they had “decided to promote Laroq because of the great job she is doing.” (Brunton claims that she later learned that “no investigation into her report of discrimination had been conducted and no witnesses were interviewed.”)

During the same meeting, Brunton contends that she informed Cohen and Labat that “she could no longer work there if Laroq was her boss,” allegedly prompting Labat to warn her, “You better watch out. You better be careful.”

The aforementioned “hostile work environment, disparate treatment, and an atmosphere of adverse employment actions and decisions culminated in [her] constructive discharge because of her race and ethnicity in violation of [her] statutory and constitutional rights,” Brunton claims. Moreover, she argues that the defendants, “unlawfully and without cause, retaliated against [her] as a direct result of [her] complaining about the incidents of race and ethnicity discrimination and a hostile work environment.” And still yet, “because she protested the defendants’ unlawful behavior,” Brunton claims that she “was subjected to retaliation throughout the course of her employment,” and that such alleged retaliation “substantially interfered with [her] employment and created an intimidating, offensive, and hostile work environment.”

With the foregoing in mind, Brunton sets forth claims of race discrimination, racially hostile work environment, and retaliation in violation of 42 U.S.C. § 1981, the New York State Human Rights Law and the New York City Human Rights Law against EDUN and LVMH, and is seeking damages “no less than” $2,000,000 in connection with her causes of action. As for why, EDUN’s since-divested minority shareholder LVMH is named as a defendant when EDUN is Brunton’s former employer, chances are, it is a strategic move to target the deeper-pocketed party, and one that is still in operation.

Since Brunton filed suit, LVMH has successfully sought to remove the case from the Supreme Court of the State of New York to a New York federal court on the basis that her “first cause of action for race discrimination and her second cause of action for retaliation are both brought pursuant to the Civil Rights Act of 1866,” a federal statute, and that her other state law claims “are substantially related to, and arise out of the same nucleus of operative facts as, Plaintiff’s claim under the Civil Rights Act of 1866 such that they should all be tried in one action.” The case was transferred to the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of New York on March 8.

Edun-Americas made headlines in June 2018 when it was revealed that LVMH had divested itself of its 49 percent stake in EDUN, and the brand had decided to formally shutter its U.S. operations. It appears that the brand has since discontinued all operations both in and outside of the U.S.

A representative for EDUN-Americas could not be reached, and a rep for LVMH declined to comment.

*The case is Brunton v. Edun-Americas, Inc., et al., 1:21-cv-02001 (SDNY).