Getting ahead of sales for the Fall/Winter 2021 season, Mackage is waging a legal battle over the design of one of its hottest-selling offerings: a certain fur-trimmed collar coat, which the nearly 25-year-old brand claims that it has consistently sold since 2007, and which rival Canadian outerwear-maker Rudsak has since “willfully and slavishly” copied and began passing off as its own in an attempt to piggyback on the esteem of “one of the most prestigious contemporary outerwear brands in North America.”

According to the complaint that it filed in a New York federal court on Wednesday, A.P.P. Group Inc., d/b/a Mackage (“Mackage”) asserts that beginning in the summer of 2007, it started selling a $1,000-plus winter coat, which bears what is now widely known as the “Mackage Collar.” Used in conjunction with its signature “asymmetrical zipper” design on “a significant portion of its core collection, [which are some of] its best-selling styles year after year,” the Montreal-based brand claims that the design has become an “outerwear phenomenon” and “a favorite among celebrities,” such as Gwyneth Paltrow, Meghan Markel, and Madonna.

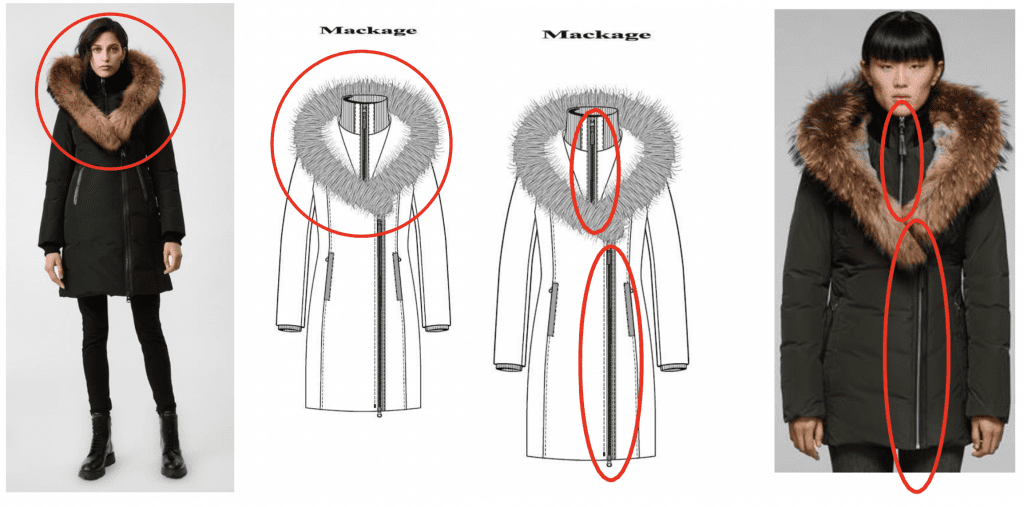

As a result of such consistent use and widespread advertising, and its adoption by well-known fans, Mackage says that the coat design – namely, “(i) the signature V-shaped fur-collar/hood used on the many of its best-selling coats; and/or (ii) the asymmetrical zipper used to close several of its coats” – represents “an asset of substantial value and has acquired substantial secondary meaning as an indicator of source.”

Against that background, Mackage alleges that Rudsak – a “direct competitor” that is also headquartered in Montreal – is offering up jackets that make use of the same key elements of its jacket trade dress in order to “willfully trade upon the goodwill of [Mackage’s] intellectual property.”

Specifically, Mackage asserts that 27-year-old Rudsak’s copycat wares are the result of an elaborate “scheme,” which sees it “deliberately hire ex-Mackage employees, including sales managers, marketers and sourcers who are intimately affiliated with the unique aspects of Mackage’s designs, fits, models, sketches and other production details, then utilizes them to copy Mackage’s style nearly verbatim.” In doing so, Rudsak “knowingly violates” the agreements with confidentiality provisions, and restrictive covenants that Mackage requires its employees to sign, the plaintiff asserts, arguing that Rudsak “violates these agreements and/or evades them by retaining Mackage’s ex-employees as ‘consultants’ rather than employees, to obtain Mackage’s proprietary information and manufacture and sell nearly verbatim copies of [its] coats.”

Beyond that, Mackage claims that “Rudsak [has] routinely purchased Mackage coats, and instructs its employees to measure and copy them nearly verbatim,” (not an uncommon claim when it comes to copying in the fashion industry), thereby, taking advantage of Mackage’s “expenditures, labor, skill and knowledge,” and “unlawfully interfering with Mackage’s property rights.” And still yet, Rudsak is further damaging the Mackage brand and potentially confusing consumers, per Mackage, by not only selling “copycat” versions of its most well-known coat but by selling an array of other lookalike styles (at lower prices and of “substandard” quality), going so far as to mimic the “marketing and advertising the style, [by] utilizing a similarly dressed model.”

In doing so, Mackage argues that has Rudsak “has caused and is likely to continue to cause” confusion among consumers as to the source and/or nature of the unaffiliated coats, is “diminishing [Mackage’s] reputation for both quality and style,” and has “created a dilutive, blurring, and tarnishing effect on [Mackage’s] famous trademarks and trade dress.”

Setting out claims of trade dress infringement, false designation of origin, unfair competition, trade dress dilution, and unfair business practices, Mackage is seeking unspecified monetary damages, as well as injunctive relief to bar Rudsak “from manufacturing or selling any goods similar to, derived from, or otherwise utilizing, copying or incorporating the Mackage trade dress,” among other things.

Unless the case settles, it could prove to be a lengthy battle. Given the presence of other V-shape fur trimmed jackets in the market, and/or the use of similar asymmetrical zipper designs on outerwear by brands, such as Moncler, Michael Kors, DKNY, and Cole Haan, it could prove difficult – and expensive – for Mackage to show that consumers have come to associate its trade dress with a single source and/or that they are likely to be confused as to the source of the Rudsak jackets.

A rep for Rudsak was not immediately available for comment.

THE BROAD VIEW: While the lawsuit centers on the U.S. market, where the parties are both competing for market share, it comes as Canadian brands are readily looking to grow their businesses beyond North America, and outerwear-makers – Mackage and Rudsak, included – are setting their sights on luxury spenders in China, where the puffer jacket market, alone, has garnered attention in recent years by generating annual sales of nearly 121 billion RMB ($18 billion) as of 2019, according to Tmall and CNBData’s 2019 Insight on Online Down Jacket Consumers report. That market is expected to grow $22.6 billion by 2022.

Such eye-watering sales in the puffer market (and the luxury outerwear market more generally) are driven, in large part, by Canada Goose, Bosideng and Moncler, which maintain an oligopoly. In terms of upscale winter outerwear, Jing Daily previously reported that the market is “split between dominant local players, such as Bosideng, innovative luxury trendsetters like Moncler and international disruptors new in the space, such as Nivose and Mackage,” the latter of which has been expanding its physical footprint in China in recent years. All the while, its “V” collar jackets are “faring particularly well among netizens,” helped along in large part by the adoption of the jacket style by celebrities in the West and famous faces in China.

At the same time, WPIC Marketing + Technologies CEO Jacob Cooke reveals that Montreal-based Rudsak is a “recent success story of new Canadian brands in China,” and one of a number of examples of “evidence that doing business in China is still possible” even as late entrants to the market and in light of the rising popularity of China’s home-grown brands, such as fast fashion behemoth SHEIN, among consumers. “When you look at competition 5-10 years ago, you talk about what other foreign brands are coming into the market,” Cooke says. “You did not really have to worry about local brands – but that is not the case anymore.”

The case is APP Group (Canada) Inc., et. al., v. Rudsak USA Inc., 1:21-cv-07712 (SDNY).

Updated

January 9, 2024

A panel for the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit issued a mixed ruling, upholding the lower court’s dismissal of Package’s “over broad” trade dress infringement claim against Rudsak, but reviving its unfair competition claim in order to enable the plaintiff to amend its complaint.