MSCHF – the maker of the big red boots that are garnering widespread media attention as of late – has lodged an amicus brief in the case that pits Jack Daniel’s against dog toy-maker VIP Products over the latter’s sale of squeaky dog toys that Jack Daniel’s claims infringe and dilute its trademark rights. In one of the latest briefs to be waged in the case, MSCHF asserts that “Jack Daniel’s and its amici seek to suppress [the] free flow of ideas” that is protected under “long-standing First Amendment precedent.” The Tennessee-based whiskey manufacturer’s “proposal suggests speech should be limited to clear speech or the safe haven of pre-approved mediums enforced through content-based regulations,” MSCHF asserts, urging the Supreme Court to “reject their effort,” and “instead of contradicting centuries of precedent … to honor established First Amendment principles.”

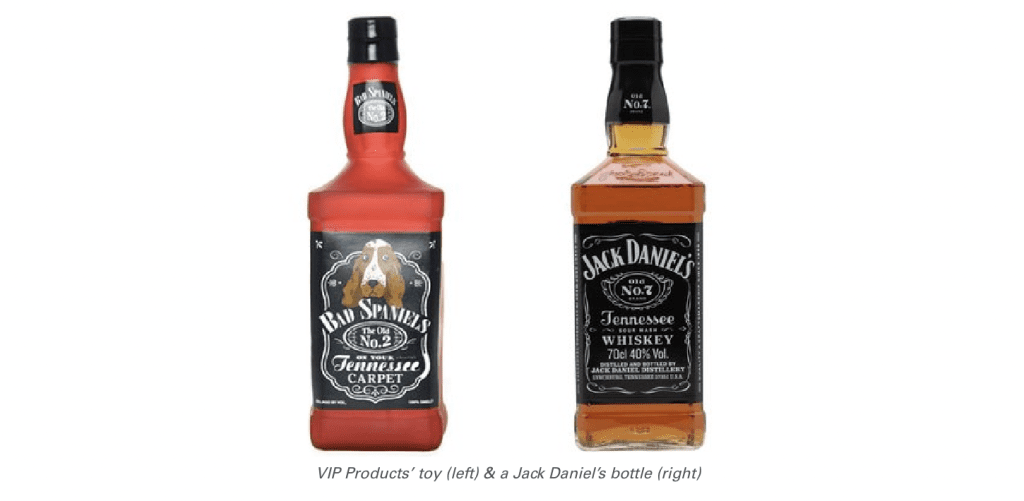

For Some Background: Siding with Jack Daniel’s in the declaratory judgment action that VIP Products waged against it in September 2014, the district court in Arizona found that VIP’s dog toys infringed Jack Daniel’s trademarks – including the JACK DANIEL’S and OLD NO. 7 word marks, and “the distinctive square shape of its whiskey bottle” – and tarnished Jack Daniel’s reputation. On appeal, the Ninth Circuit overturned the lower court decision, holding that VIP’s chew toy was an expressive work entitled to protection under the First Amendment.

The Supreme Court granted Jack Daniel’s petition for certiorari in November 2022, and is tasked with considering: (1) Whether humorous use of another’s trademark as one’s own on a commercial product is subject to the Lanham Act’s traditional likelihood-of-confusion analysis, or instead receives heightened First Amendment protection from trademark-infringement claims; and (2) Whether humorous use of another’s mark as one’s own on a commercial product is “noncommercial” under 15 U.S.C. § 1125(c)(3)(C), thus barring as a matter of law a claim of dilution by tarnishment under the Trademark Dilution Revision Act.

MSCHF’s Brief: Setting the stage in its brief (a fair amount of which is filled with pages of connect-the-dot puzzles for each of the Justices and their clerks to complete and return to MSCHF for inclusion in its impending “Where to Draw the Line” group art exhibition), MSCHF points to ad campaigns and logos from the likes of Marlboro, Supreme, Starbucks, Coca-Cola, Budweiser, and Oreo, along with an array of political merch, as examples of how companies “routinely take from art and culture and add their message to imbue their [trade]marks with meaning,” and at the same time, how “artistic and political speech uses the cultural resonance of trademarks for their own expression.”

For example, MSCHF cites the Supreme box logo, stating that “in 1994, Supreme’s CEO wanted a symbol for his fast-fashion store, so he gave their designer a book of Kruger’s work to develop a logo.” The result, according to MSCHF, “inverts the artist’s message while borrowing her aesthetic to lend an air of pop art to Supreme’s fashion offerings and suggest it is a rebellious brand ‘outside fashion.’” The appropriation worked, it contends, as “now Supreme is a worldwide clothing and skateboarding company.”

Calling on the court to affirm the decision of the lower courts in the case, and clarify that noncommercial uses of trademarks are fully protected by the First Amendment, MSCHF argues that by looking to ban “the use of commercial or utilitarian goods for expression they do not approve, and only for expression they do not approve,” Jack Daniel’s “proposes an unconstitutional content-based regulation.” Not only does the First Amendment “not permit regulation that privileges certain categories of expression, on specified mediums, over other categories of expression,” MSCHF claims that a limitation to “only permit licensed commentary about trademark holders also violates the bedrock First Amendment principle that government may not ‘regulate speech in ways that favor some viewpoints or ideas at the expense of others.’”

Another key contention in MSCHF’s brief is its argument that the likelihood of confusion (“LOC”) test – which is used to determine if use of another’s trademark is infringing – “censors protected speech.” In addition to citing an array of cases, including Rogers v. Grimaldi, as examples of instances in which ad campaigns and artworks would have been banned if the courts applied LOC test (instead of … say, the Rogers test), MSCHF states that its “own experience demonstrates the problem.” On two occasions (i.e., in the currently pending Vans case over MSCHF’s Wavy Baby sneakers), MSCHF maintains that “courts entered a preliminary injunction finding that our artwork would likely confuse customers.” Yet, “of the more than 5,000 pieces of art we distributed prior to entry of those injunctions,” MSCHF says that “not a single patron ever expressed actual confusion.” Unsurprisingly, it claims that “VIP’s experience is similar.”

MSCHF alleges that the LOC test is also “unpredictable,” and not mincing words, “a mess, with different circuits weighing different factors differently and ‘excessive inter-circuit variation in the application and outcome.’” Still yet, MSCHF states that when the LOC test is applied to noncommercial speech, it is “overbroad,” as it serves to “ban political and artistic speech, censors speech unless ninety-one percent of the public understands the message, suppresses speech by being unpredictable, and it conflate copyright and trademark law to censor legitimate expression.”

As for the case at hand, MSCHF asserts that “VIP’s Silly Squeakers are a series of dog puns, each one heightened by placement on a dog toy. The speech is the toy. Like placing the political statement ‘Truth over Flies’ on a fly swatter, the use of the dog toy heightens the dog joke, which intertwines the expression and the good.” This is the same type of non-commercial speech as was found in Fellini’s film in the Rogers case, MSCHF says, and thus, it “is fully protected by the First Amendment without need for additional analysis.” Put another way, MSCHF argues that “the appropriate test is to ask: What is sold? If it is speech, then the use of a trademark is noncommercial and permissible. Here, VIP sells a joke. The parody comments on how dog owners like to humanize their animals, and the role of alcohol branding in society.”

“As noncommercial speech, the Constitution fully protects the joke from censorship,” MSCHF argues at the end of its brief, stating that “there is no reason to change centuries of expressive traditional to protect those with the largest speakers.”

The Supreme Court will hear oral arguments in the case next month.

The case is VIP Products LLC v. Jack Daniel’s Properties, Inc., 2:14-cv-02057 (D. Arizona).