Look closely at Vogue Runway’s review for Moschino’s Spring/Summer 2016 collection, the one in which the Italian design house showed its legally-questionable Windex-inspired wares, as well as some other notable references. A couple of choice excerpts from the fashion publication’s review of creative director Jeremy Scott’s latest Moschino wares are as follows: “Chanel-style skirt suits came in flashy neons with flashier reflective-tape edging” and “Scott played fast and loose with Chanel-isms, most literally and perhaps dangerously with a print of interlocking C clamps.”

The Moschino fans amongst us will know that this is hardly the first time that Scott and Moschino have referenced Chanel or other key fashion and pop culture references; in fact, Mr. Moschino, himself, was quite well-known for his popular references. Look back a year and a Vogue Runway columnist noted in connection with Moschino’s S/S 2015 runway collection (the Barbie one): “See the pool-floaty ‘Chanel’ handbags.” In re: the house’s corresponding menswear collection that same season, another Vogue writer noted: “Scott surely had a ball with Moschino ideas, creating Chanel-like logos from interlocking smileys.”

And lest we forget Moschino’s Fall/Winter 2014 collection, of which Vogue Runway (then still technically Style.com)’s Tim Blanks wrote: “Scott paraded his mutant hybrid of Ronald McDonald and Coco Chanel, and his Budweiser and Frito-Lay couture.” The famed critic elaborated, writing: “Any single piece of Chanel iconography you could imagine was twisted every which way.” It might seem as though I’m singling out Vogue and I am. This is because out of all the truly major reviews of the recent Moschino collections, Vogue is the only publication (online or otherwise) to make specific references to Chanel.

The Trademark Holder’s Duty: Policing its Mark

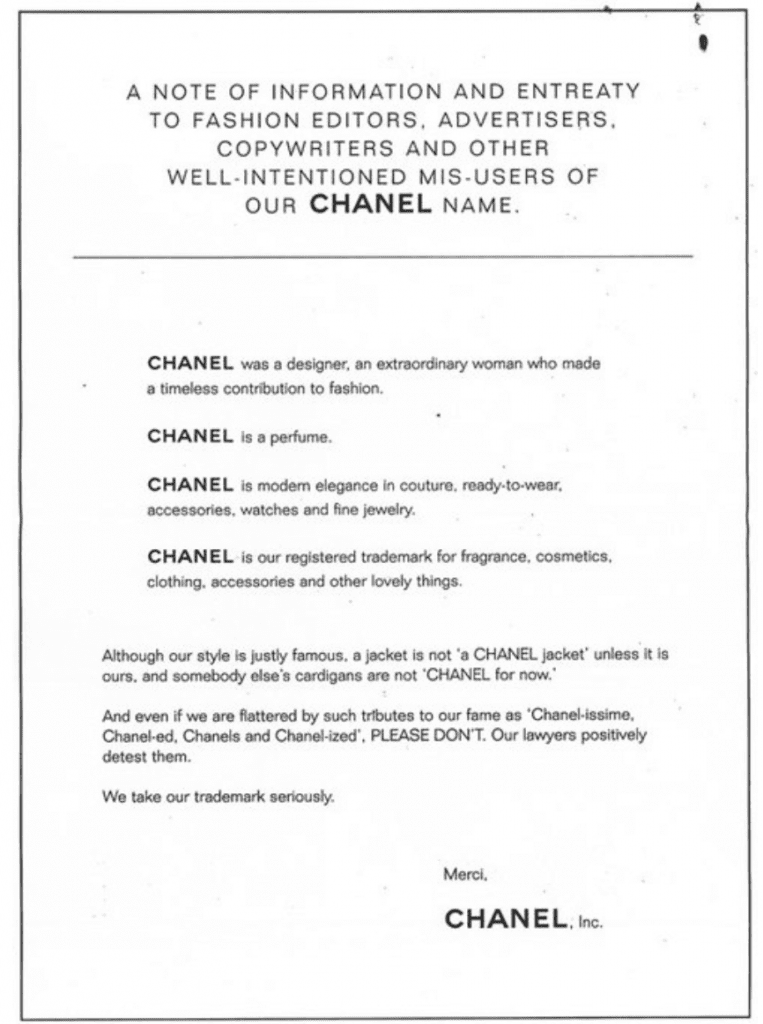

So what? Why does this matter? Well, Chanel hates it, and the house has made its feelings on the matter very public. You may recall that beginning in 2009, the Karl Lagerfeld-helmed house began running ads in trade publication Women’s Wear Daily, which were heavily documented by others publications, that read:

Most non-lawyers, in particular, tend to share a relatively common reaction to the foregoing ad (and the trademark infringement and/or dilution lawsuits that often follow); they conclude that Chanel is being overzealous, and acting like a big bully in connection with its various trademarks. However, if we consider just how trademark law works and the duties that are placed on trademark holders, Chanel’s course of action (in the case at hand) makes a lot more sense.

As you probably already know, a trademark is a word, phrase, symbol, product shape, or logo used by a manufacturer or merchant to identify its goods and to distinguish those goods from those made or sold by others. The purpose of trademark law is twofold: first, it is to aid the consumer in differentiating among competing products and second, it is to protect the producer’s investment in reputation. In short: a trademark allows the consumer to make judgments concerning the quality of the goods before sampling them. For example, when a consumer sees a Chanel bag, the Chanel name and its double “C” logo (both of which are federally registered trademarks that belong to Chanel) they convey a level of quality regarding the bag that is higher than many other bags on the market. He or she can discern this simply from seeing the name and/or logo.

It is also worth noting that unlike some other forms of intellectual property protection (namely, patents and copyrights), trademark protection can potentially last forever, as long as the trademark is being used in commerce and has not been subjected to genericization. The latter terminology refers to the level of distinctiveness of the mark. As you may (or may not know), a word or a logo, etc. can only be considered a trademark if it is distinctive. Per Bit Law, “A distinctive trademark is one that is capable of distinguishing the goods or services upon which it is used from the goods or services of others. A non-distinctive device is one that merely describes or names a characteristic or quality of the goods or services.”

Just because a trademark was once distinctive does not mean it will always be distinctive. In fact, over time, a trademark can lose its ability to serve as an identifier of source and thereby, become merely generic. This tends to occur due to misuse of the mark over time. For example, at one time, aspirin, laundromat, trampoline, and videotape were all trademarks afforded protection under federal law. However, over time due to improper use, the marks slipped into the public domain and thus, may be used by anyone without giving rise to trademark infringement lawsuits.

As such, it is the trademark holder’s duty to make sure that others do not misuse its mark, and in order to do so, trademark holders must police the use of their marks and take action accordingly.

The Value of Trademarks in the World of Fashion

More than just a logo or a brand name, trademarks are particularly valuable in the luxury sector, where the fashion industry firmly resides. Quite often, the first thing that draws many shoppers to a brand is not the quality of its goods or the design of the garments/accessories themselves. It is the brand’s reputation, which is oftentimes signified by any of its various trademarks, that tends to draw in a large portion of consumers. Take Louis Vuitton, for instance. Do consumers lust after its Toile Monogram bags because they find the brown and gold print aesthetically appealing or because the brand’s quality is unprecedented, OR because of the message that such a bag sends (or once sent, depending on where you stand in terms of logo-fatigue at the moment) to the consumer, her friends, and society at large? My money is on the latter. Fashion’s “it” bags are viewed as status symbols for a reason, after all.

With this in mind, fashion brands’ intellectual property, particularly its trademarks, serve as a very significant asset. It is, in a sense, what allows them to charge a premium — something that is absolutely essential in the luxury sector, where bags tend to cost at least $1,000 and garments even more.

Enter: Chanel and its (now very notorious) warning message, which has appeared in a number of issues of WWD. How did the brand get to the point that it was forced to begin running full page ads in industry publications asking “fashion editors, advertisers, copywriters and other well-intentioned” individuals to kindly refrain from using its name to describe the goods of other brands?

Well, it is most likely because Chanel has a handful of specialty pieces – truly iconic ones – in its repertoire and it has for over a century (Chanel was founded in 1909). These are the things for which Chanel is known: the tweed jackets, quilted purses, double “C” logo-adorned makeup cases, skirt suits, etc., which have been token items for the brand. As a result of the success (and subsequent re-introduction and subsequent re-introduction and subsequent re-introduction, etc.) of such items, writers, designers, and fashion fans, alike, have come to know of these things (and regard them) as distinctly Chanel. Not surprisingly, as we saw in Vogue Runway’s reviews, that same group of individuals has found it useful to utilize the word “Chanel” as an adjective to describe those items and similar ones, even when they originate from a brand that is not Chanel. For the reasons set forth above, this is problematic.

In short: such improper usage of the Chanel name puts the design house in a position in which it could lose its trademarks (by way of genericization) and in connection therewith, it could lose the reputation, the level of status and exclusivity, the aura of high fashion and luxury, and the brand identity it has been working to perfectly position for the past century. If we look at it this way, such warning messages seem a bit less bully-like and a lot more reasoned, no?

So, What About Vogue?

But back to Vogue. It seems that the majority of industry publications have gotten the memo, so to speak, with regards to the parameters of the use of the word “Chanel” in connection with the products of other brands, and yet, Vogue is defying the trend. This raises the question: How does Vogue get away with it? And should we be expecting to see one of Chanel’s warning ads in the pages of Vogue in the near future?

What we do know is this: While the Paris-based design house has never been shy to initiate a court battle in connection with its intellectual property, Vogue is probably not a tree it wants to bark up; it is, after all, one of the most influential fashion publications known to man. Thus, such unabashed and unpoliced use of the Chanel name may be a testament to Vogue’s power.

However, at the same time, it is fairly surprising that Vogue has been so blatant with its outside-of-the-realm-of-preferred-usage of the Chanel name given the fact that Chanel is certainly a major advertiser and has been for years. As Luxury Daily noted in connection with Vogue’s June 2013 issue, “Chanel takes the first four pages of the issue. A couple of pages later, it has another two-page ad to show off its eyewear, and the brand has another one-page ad for its Le Rouge campaign next to the table of contents.” Per Ad Age, Chanel spent $78.3 million on advertisements in U.S. magazines alone that year. And as we know from both analysts’ reports and from simply flipping through the pages of more recent issues of Vogue, Chanel has not shied away from classic print advertising.

As Hillary Milnes noted in a DigiDay article, the brand still “loves print, because it gives them a large palette to market.” As such, it is downright surprising that Vogue’s columnists have not changed their ways to more closely conform to Chanel’s legally-minded requests.

At the end of the day, this situation seems to shed light on the larger dynamics of potential litigation and the multi-faceted approach that smart brands tend to take when deciding if and when to file a lawsuit. Not surprisingly, non-legal concerns come into play when considering whether to file legal action or not. Brands and their legal counsels always balance the resources required to file and actually pursue a lawsuit with the potential outcome to be gained by such a suit – this is a no-brainer. But then there are things that come into play that must be taken into account, such as an existing symbiotic relationship between the two parties (the potential plaintiff and the potential defendant) and the probable burning of a bridge, so to speak, as a result of the litigation. There is also the potential role that bad press or no press at all could play as a result of filing a lawsuit.

There is also the chance that Chanel would lose! As for how a judge would actually rule in such as case is another question entirely, especially if we consider First Amendment concerns.

Still yet, there is this question: Just how harmful is the allegedly infringing use? As we noted in connection with the lawsuit that McDonalds could have likely filed against Moschino and Jeremy Scott in connection with the Italian design house’s Fall/Winter 2014 collection, sometimes the allegedly infringing use is to the IP holder’s benefit. As we wrote in connection with that collection:

Unlike Chanel, a historic design house with high fashion image to uphold (which may, in fact, be infringed by Moschino’s “odes”), McDonald’s could probably afford to up their image game just a bit, no? Thus, its connection to an Italian design house may not be the worst thing in terms of branding. And consider the exposure. We have all heard that no press is bad press, and that same reasoning likely applies here. When was the last time McDonald’s was in Vogue or Womenswear Daily or any fashion-related publication?

These are just a few of the non-legal centric issues that are certainly taken into account when there is a legal issue at hand, and may, in many cases, play an even larger role in dictating whether brands decide to sue than the plain old black letter law itself. And judging by the lack of litigation between Chanel and Vogue, there is a chance that Chanel has weighed its options and decided against it, the parties have some other understanding to which we are not privy, or this is a lawsuit in the making.

UPDATE (2/26/16): It seems Vogue is not the only guilty party here. On the heels of Alexander Wang’s Fall/Winter 2016 show, a number of others have opted to do what Chanel “positively detests.” Peter David, publication director for the Daily Front Row, for instance, who has been documenting NYFW by way of his Twitter account, noted: “Alexander Wang’s new Chanel-esque collection.” One of fashion site wrote about the “Chanel-inspired tweed skirt suits and dresses.”

Not everyone got it wrong, though. The Paris-Based design house would certainly much prefer the Observer’s description of the garments at issue; the publication’s columnist Dena Silver opted to describe them as “tweedy suits,” thereby, leaving out the house’s trademarked name. Similarly, the Telegraph’s Sophie Warburton referenced the “Tweed mini dresses,” instead of calling them Chanel-like. With Chanel’s known history of litigation, I’d suggest others follow suit.

* This article was initially published in February 2016.