There are a lot of potential complications that can come from naming your brand after yourself. Some of the most obvious issues arise in the M&A (mergers and acquisitions) context. Or more specifically, they come after a buy-out is complete, and the individual that lent his/her name to the since-sold brand is looking to take on their next endeavor, potentially a new brand. As has been a problem time and again, if that new venture is anything like the former venture, that individual is bound to run into trouble if they attempt to slap their name – or even a variation or part of their name – on it.

“When your name is not only your [personal] moniker but also your brand, comprising trademarks, goodwill and reputation, it is no longer an inconsequential appellation but a valuable asset,” Collyer Bristow LLP wrote in a client note a few years ago. “And yet, names seem to be rather difficult to retain in the label-centric world of fashion, where an increasing number of founders of namesake labels have lost” – or maybe more realistically, sold – “the right to trade under their own name.” The London-based firm cites examples, such as “Helmut Lang cutting ties with the Helmut Lang label back in 2006, [and] Roland Mouret, the creator of the iconic ‘Galaxy dress, losing the right to use his own name when he suddenly left his eponymous label.” (Collyer Bristow notes that Mr. Mouret “had to adopt the rather cumbersome brand name, ‘RM by the designer Roland Mouret’ until 2010 when he re-acquired the ‘Roland Mouret’ trademark and was, once again, able to trade under his own name.”)

And still yet, ” Jo Malone is no longer behind the fragrance empire that bears her name; she had to endure exile from the industry for several years until she was able to launch her new line, ‘Jo Loves,’ in 2011,” Collyer Bristow further stated.

In a more recent example of how this can play out, beauty mogul Bobbi Brown revealed this fall that she was getting back into the makeup business by way of a new brand. Not coincidentally, Brown, who sold her eponymous beauty label to Estée Lauder in 1995 but stayed onboard for more than 20 years afterwards, launched Jones Road shortly after the reported expiration of a four-year-long non-compete agreement that she signed when she left her Estée Lauder-owned label in December 2016. But more significant than the restrictions on her ability to compete in the beauty space (either via a new brand of her own or by way of an already-existing competitor) for the duration of the legally-binding agreement, however, are the enduring limitations on her ability to use her name.

In selling her company to Estée Lauder almost 30 years ago, Brown traded off certain rights in her name in exchange for a pay day, as is customary in such deals. After all, one of the most central elements of a brand acquisition is the transfer in ownership of that company’s intellectual property, including trademark rights in the brand name, logos, etc. In that case, that was the trademark-protected “Bobbi Brown” name for use on everything from cosmetics products, themselves, and retail (and online retail) services associated with the sale of cosmetics to eyewear fragrances, and various categories of related goods and services, as well as related marks.

Against that background, Brown is unable to launch a new brand under her name, regardless of the fact that Bobbi Brown is her personal name (she is, of course, perfectly free to use her name in her personal capacity, as that is distinct from use in commerce), which is precisely why her new venture is devoid of her famous moniker, and is, instead, called Jones Road.

From the outside looking in, Brown’s departure from her eponymous label and subsequent launch a new company in the same space is an example of a peaceful transition, which is not always the case. Joseph Abboud, for instance, is an example of the alternative. The menswear designer landed in the middle of a famous legal battle over his ability to use his name and/or parts of his name after selling off his namesake brand, thereby, exemplifying the typical cautionary tale imparted upon creatives that are considering launching – and maybe one day, selling – an eponymous label of their own.

Another Important Issue

In addition to considering the limitations on name use that eponymous brand builders will inevitably face in a post-sale scenario, there is a separate but equally critical element that brand builders should take into account, and it centers of whether a personalized brand is the way to go for well-known figures in the context of attracting investors and/or acquirers, and in connection therewith, whether it is the best approach in terms of garnering the greatest valuation for the company.

In a recent piece for Bloomberg, technology, media and communications columnist Alex Webb considered this potential downside of the eponymous path, citing Jay-Z’s champagne brand Armand de Brignac – 50 percent of which was recently snapped up by LVMH – as a prime example of a successful approach. He name-checked George Clooney’s Casamigos, which sold to Diageo Plc in 2017 in a deal valued at $1 billion, and fellow actor Ryan Reynolds’s Aviation American Gin company and its $610 million acquisition by Diageo last year. Jessica Alba’s Honest Company, which made its stock market debut on May 4 with a $2 billion valuation, also comes to mind, per Webb.

In each of those cases, the celebrities have been more-or-less at the forefront of the brand with which they are associated either as a founder or primary investor or both. If you have ever seen a Casamigos delivery truck, you will know that they often feature large-scale photos of Clooney and his partner Rande Gerber on the side. Reynolds regularly stars in Aviation’s notoriously humorous ad campaigns. Honest Co. is routinely referred to as “Jessica Alba’s company,” with the actress-turned-entrepreneur’s photo littered across the consumer goods company’s website. And not to be outdone, there are no shortage of images of Jay-Z (and spouse Beyoncé) drinking champagne from his Armand de Brignac – or “Ace of Spades” – venture. The couple famously brought their own Armand de Brignac with them to the Golden Globes last year, prompting seemingly endless media attention.

The same level of marketing cache and reach is in play for companies like Kylie Cosmetics, the $1 billion-plus brainchild of Kylie Jenner, Rihanna’s burgeoning “Fenty” ecosystem, and the likes of Yeezy (which although not Kanye West’s birth name, is, nonetheless, a nickname that is readily associated with the rapper-slash-designer), etc. – in that the famous founders regularly serve as the focal point of the brand and its marketing efforts.

The difference between these brands, and Armand de Brignac, Casamigos, Aviation, and co., is not the presence of uber-famous faces. Instead, it is the latter’s “arm’s length approach to branding, [which] seems to work well for selling the business for a hefty fee,” Webb writes. “After all, if the company is not inextricably tied to a celebrity’s cachet, it is easier for an acquirer to turn it into a standalone operation” if and when that famous figure decides to walk away – or if that person embroils himself/herself in a situation that results in public relations fall out.

The added layer of padding, so to speak, protects the brand in cases of emergency, as well as when it comes to succession planning without having to go at it without a famous founder. “Both the Casamigos and Aviation deals [with Diageo],” for example, “have earn-out agreements, meaning the full sum will only be paid to the sellers if the brands meet certain goals over the course of a decade,” Webb notes. “That keeps the stars invested,” while also essentially acting as a safeguard or an automatic morals clause.

“That protection is harder to come by when celebs are the face and name of the product,” according to Webb. Such a divide provides that; it also stands to proactively tidy up messes that could result from right of publicity/misappropriation issues down the road, such as those currently causing legal sparring matches between Sean “Diddy” Combs and GBG, the company that acquired Sean John, the eponymous brand that the musician launched in 1998, and that has since sought to actively align itself with Mr. Combs after the fact.

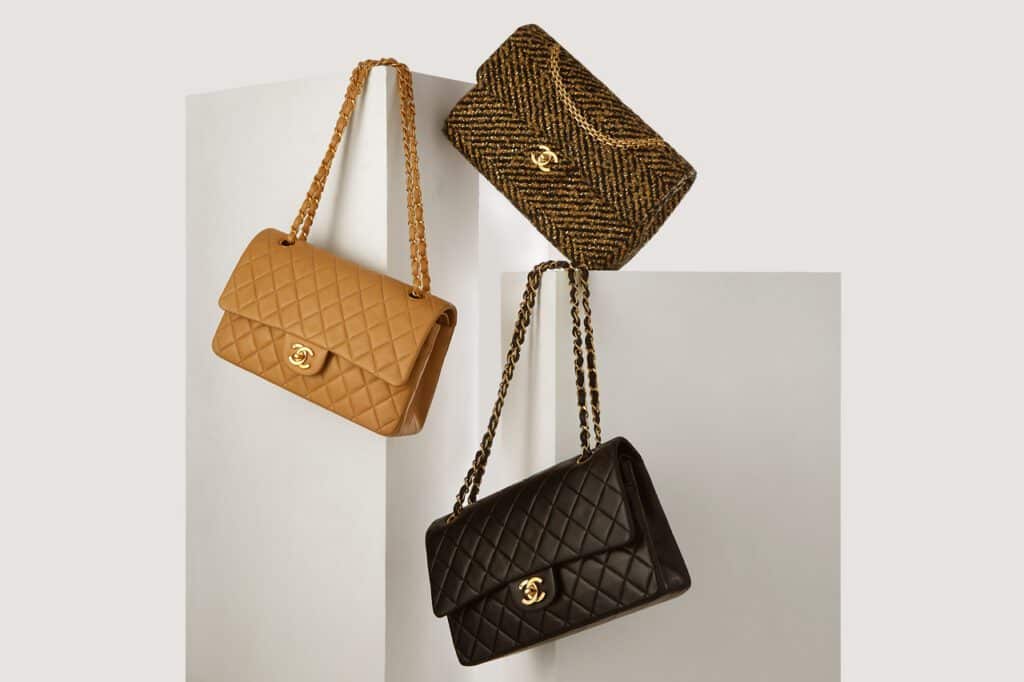

Ultimately, “Celebrity brands are not a new phenomenon,” Webb aptly notes, pointing to boxer George Foreman’s grills, legendary actor Paul Newman’s namesake food company, and tennis star Rene Lacoste’s eponymous sportswear label. And in fact, in the fashion and luxury space, they proved to be to go-to naming approach for decades, with some of the most famous luxury brands in the world getting their names from individuals’ full monikers (Louis Vuitton and Christian Dior come to mind) or their surnames (think: Hermès, Cartier, Chanel, Ferrari, and Gucci, the brand of the late Guccio Gucci).

While that is still the case to some extent, and new brands bearing their founders’ names continue to come into fruition, it appears that at least some smart founders – whether they be famous figures wading into the consumer brand territory or newbie designers launching their own labels – are thinking twice about what it means to name your brand after yourself.

UPDATED (May 4, 2021) to reflect to valuation of Honest Co.’s IPO.