Ahead of the court deciding on Nike’s motion for a preliminary injunction to stop Warren Lotas (“WL”) from selling its allegedly infringing sneakers, WL filed its answer to Nike’s amended complaint, in which it denied most of the company’s assertions, including that its sneakers have infringed Nike’s trademarks. In terms of the defenses set forth by WL, a number of them – waiver, estoppel, and acquiescence – center on the company’s interesting assertion that Nike “collaborator and apparent agent” Jeff Staple, who is not a party to the lawsuit (on either side), “affirmatively authorized” WL to make the Warren Lotas X Staple Pigeon OG sneaker, “including the colorway, logos, and design of the shoe and sole.”

In making such an assertion, WL is essentially claiming that because Staple permitted it to recreate the shoe, complete with legally-protected elements of Nike’s branding, that that removed the need for WL to get Nike’s authorization, as well. That is, of course, not how that it works, as evidenced by the filing of this lawsuit.

(It is worth noting that Staple does, in fact, maintain trademark rights in (and a trademark registration for) the little pigeon logo that appears on the WL shoe and other offerings by his own Staple Pigeon brand. As such, in order to legally replicate that mark on its sneakers, WL would need Staples’ authorization. Based on the language of its marketing and Staples’ promotion of the WL sneaker, and the based on WL’s allegations in the case thus far, it appears that WL got Staple’s permission to use the pigeon logo. But this lawsuit evidences that WL did not go a step further and receive the go-ahead from Nike to make and sell the shoes, which is necessary since Nike – not Jeff Staple – is the one that has exclusive rights in the swoosh logo, trade dress-protected Dunk design, and the “Dunk” word mark.

This is true even if Staple did, in fact, collaborate with Nike in creating the original Pigeon Dunk sneaker. (In collaboration situations, the brand almost always maintains rights in the designs at play).

Given that Nike is the sole owner of the Dunk and swoosh trademarks, and assuming that Staple is not authorized/able to act on behalf of Nike when it comes to Nike’s trademarks (which is a safe assumption), in order to legally replicate the Dunk sneaker, and use the “Dunk” work mark and swoosh logo, WL would need Nike’s permission, which it allegedly did not have).

Nonetheless, WL claims that because it got Staple’s authorization to make the shoe, Nike “actively represented or assured [WL]” – via Staple – “that it would not assert its trademark rights,” and that it “intentionally and unequivocally relinquished its trademark rights.” WL also claims that as a result of the fact that it got Staple’s authorization to make the shoe, it “did not know and had no reason to know that [Nike] actually objected to [its] purported conduct.”

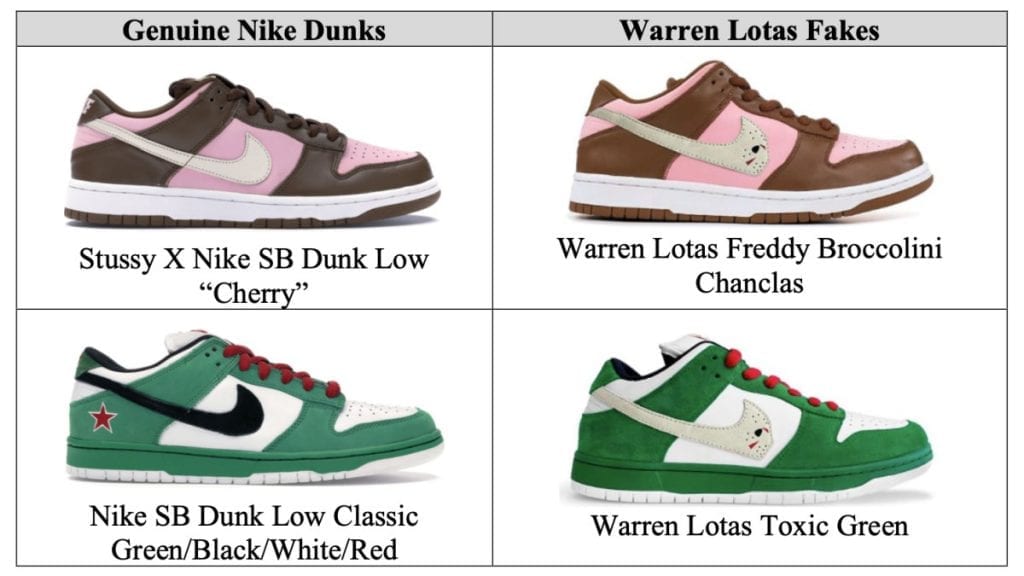

More than that, WL claims that Nike’s claims are “barred, precluded, and/or limited by the doctrine of naked licensing,” as “Nike has permitted rampant, unpoliced use by third parties of its purported trade dress, including the Dunk trade dress,” and as a result of “Nike’s failure to police such third-party usage and/or control the quality of such third-party use, [it] has caused the purported trade dress to cease functioning as a symbol of quality and a controlled source.”

In a separate defense (and in its two counterclaims), WL takes issue with Nike’s trade dress rights, arguing that “one or more of [Nike’s] alleged trade dress elements in the Dunk [shoes] … such as the tread on the sole of the shoe has utilitarian functionality because such trade dress elements are essential to the use and purpose of the sole and/or affect the cost and/or quality of the sole,” and thus, are not valid trade dress rights in light of trademark law’s unwillingness to protect functional elements. With such alleged utility in mind, WL not only claims that it is shielded from Nike’s infringement claims, it argues that the court should formally invalidate two of Nike’s trademark registrations (no. 3,711,305 and 3,721,064), which respectively cover the body and the sole of the Dunk sneaker.

*The case is Nike, Inc. v. Warren Lotas and Warren Lotas LLC, 2:20-cv-09431 (C.D.Cal.).