From vying for the attention of consumers in an uber-branded marketplace to adding potentially-very-valuable new assets to their branding portfolios, the benefits of adopting colors as indicators of source are becoming increasingly evident for fashion and luxury brands. While companies like Tiffany & Co., Hermès, and Christian Louboutin have widely-known proprietary hues (and trademark rights in them), newer efforts by Bottega Veneta and Valentino, for instance, have brought color marks back into the spotlight. As such, issues that companies face in successfully claiming rights in color marks – and some of the strategies for doing so – are proving to be particularly relevant.

The notion that colors can act as indicators of source is not new, with the ability of companies to rely on trademark law to protect proprietary hues dating back to Qualitex Co. v. Jacobson Products Co. case in 1995, in which the U.S. Supreme Court decided that a single color can operate as a trademark upon a showing of secondary meaning., and the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit’s determination in the Owens Corning case a decade before that. Even though it is well-established that companies can amass rights in (and registrations for) single color trademarks, what is a bit less clear is what that actually entails for brands beyond the immediate use-in-commerce element, and what is standing in the way of registration given that just one-third of trademark applications for color marks are registered by the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (“USPTO”) each year.

The most pressing issue for brands that are looking to establish rights in their use of a single color is not secondary meaning, which Qualitex requires. (It is worth noting that in 2020, the Federal Circuit Court of Appeals reversed the USPTO Trademark Trial and Appeal Board’s finding in Forney Industries that a “color mark” can never be inherently distinctive; in that case, the trademark consisted of multi-color product packaging. In determining that “color marks” can be inherently distinctive, the Federal Circuit potentially “left open the question of whether a pure color mark used on product packaging could be registered without proof of secondary meaning,” Fish & Richardson’s Lisa Greenwald-Swire said in a note at the time.)

Secondary meaning is less of an obstacle than might otherwise meet the eye here because “if a brand is popular enough, a significant number of consumers will [eventually] associate that color with that particular brand,” University of Oklahoma Law professor Jon Lee tells TFL. Instead, the bigger hurdle for brands looking to claim trademark rights in their use of color on or in connection with clothing and/or accessories is aesthetic functionality. (A mark is aesthetically functional, and therefore, ineligible for protection, according to the Second Circuit, when such protection would “significantly undermine competitors’ ability to compete in the relevant market.”)

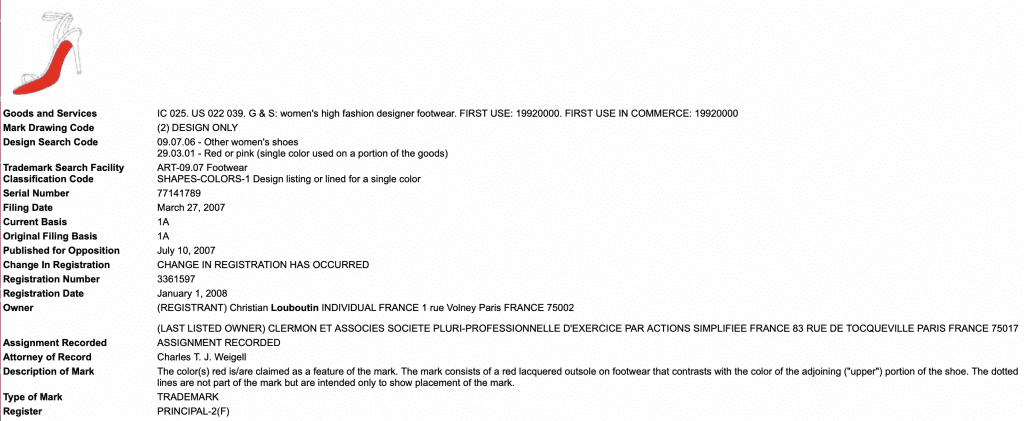

From an aesthetic functionality perspective, Lee notes that Louboutin’s red sole trademark, for example, is “relatively rare” in that it is not common that we are talking about the bottom of a high heeled shoe or another aspect of a fashion product that “consumers have not historically associated with fashion.” And so, while an aesthetic functionality issue that was raised in Louboutin v. YSL initially threatened the French footwear brand’s ability to maintain a valid trademark registration (even in light of substantial evidence of consumer recognition and the USPTO previously opting to issue a registration for the mark), the red sole has, nonetheless, proven to be “an example where the USPTO might say that a color is not aesthetically functional.” Short of that, though, “functionality with regard to clothes or accessories, themselves, would be a higher hurdle than a secondary meaning issue.”

With such potential refusal bases in mind, Lee asserts that it is likely easier in some ways for companies to try to enforce more “non-traditional” rights through litigation than to try to register them with the USPTO. A clear example of this is college brand colors. Lee points to the 2008 decision in Board of Supervisors, et al. v. Smack Apparel Co., in which the Fifth Circuit found that Louisiana State University, the University of Oklahoma, the Ohio State University, and the University of Southern California, along with their official licensee, had a protectable interest in their respective colors in association with other “insignia.” And “there is no way,” Lee says, that the schools would have been able to register such color-centric marks with the USPTO.

Another point worth noting when it comes to the ability of companies to successfully claim proprietary colors as part of their arsenal of branding is the role that market trends play. One need not look further than Bottega Green for a concrete example. During creative director Daniel Lee’s recent tenure, Kering-owned Bottega Veneta released a steady stream of “it” accessories in the hue and incorporated the color into its ad campaigns, large-scale installations (including a takeover of the Great Wall of China), stores, etc. In the process, the company managed to cement Bottega Green at the center of the fashion zeitgeist – and transform the previously dusty brand (and its leather goods) into one of the most in-demand among prized millennial and Gen-Z consumers.

Against that background, other brands – from Jacquemus to Dolce & Gabbana – began to offer up notably similar green-colored accessories of their own, likely in a quest to cater to the very-real-demand that had already been established by Bottega. The apparent effect of prompting the rise of an “it” color is the inevitable “inspiration” that will follow.

From a color trademark perspective, the influx of Bottega Green-like accessories from brands other than Bottega raises the question: Does the proliferation of the color after Bottega started using it help the company to claim that it has rights in it or does it chip away at its potential claim that consumers associate the color (when used on accessories and related packaging, for example) with a single source? Courts have not directly addressed this specific issue (that I know of). However, Lee contends that since “many of the trademark tests look to copying and/or the intent of the parties in ascertaining if a brand has a protectable trademark, the machinery is there for courts to use those facts” – including examples of copying or intent to piggyback on the recognition of consumers of a potential color mark – “to find that a brand has a protectable color mark.” This comes under the theory that “when a brand is copying it shows that there is a protectable interest to begin with; that there is a reason they are trying to trade on the reputation of another well-known brand.”

In other words, being able to point to examples of “attempts to copy” might actually prove useful for brands that are looking to establish that they have rights in their use of a color mark on or in connection with certain goods. It does not, however, remove the aesthetic functionality elephant that comes hand-in-hand with apparel and accessories. (Looking beyond Bottega Green, potentially even more interesting on the market trends front is Valentino’s PP Pink, which was introduced just ahead of the onset of the “Barbiecore” trend that has resulted in very widespread use of the hot pink across the fashion and luxury goods markets by brands ranging from SKIMS and Balenciaga to Gap and Gucci.)

Chances are, brands will have much better luck if they take a multi-pronged approach to amassing/enforcing rights in a color mark. In addition to using the color on garments and accessories, which raises red flags on aesthetic functionality grounds, companies would be wise to use such colors on more traditional mediums of branding. “If I was a brand, I would not just use the color in association with fashion [items],” Lee says, “but also on the packaging because we know it will be easier to get a protectable interest in the packaging.” (Look no further than Glossier, for example, which has trademark registrations for its millennial pink for use on product packaging related to “cosmetics; makeup; skincare products,” etc., including “the color pink as applied to bags featuring lining of translucent circular air bubbles and a zipper closure.”)

Brands can then try to parlay that packaging-focused protectable interest into an infringement claim “even if another brand were to use that color in association with a bag or other goods.”

For one final example to gauge where the USPTO and the Trademark Trial and Appeal Board (“TTAB”) stand in terms of color as of the late, the latter recently upheld an examiner’s refusal to register a non-fashion color mark – the color orange for use on “tool and tool accessory trays not made of metal sold empty and parts and fittings therefor” – on the basis that the mark “is not inherently distinctive, has not acquired distinctiveness, and thus, fails to function as a trademark.” (This is In re Grypmat, Inc.) Given that the products at play are “non-metal tool and tool accessory trays” and not handbags or dresses, for instance, aesthetic functionality was not the issue, but instead, acquired distinctiveness. (Grypmat did not claim inherent distinctiveness.) Considering the six factors set forth in the Federal Circuit’s Converse decision, the TTAB determined that Grypmat “falls short of carrying the high burden of showing that its proposed color mark has acquired distinctiveness pursuant to Trademark Act Section 2(f).”

Among other things, the TTAB pointed to a lack of look-for advertising; there is “no such demonstrated effort by [Grypmat] to point the consumer’s attention to the color orange or promote this color as a distinctive source-identifying quality.” At the same time, the TTAB found that “the number of tool and tool accessory trays sold by [Grypmat] in the previous 5-6 years, as well as its expenditures in promoting these goods over that same period, are impressive. However, high sales and advertising figures do not always equate to a finding that mark has acquired distinctiveness, especially when, as here, there is a higher burden for making such a showing.” And still yet, the TTAB said that the media coverage that Grypmat pointed to – including its two-time feature on “Shark Tank” and “attention to its goods” from publications like Time and Forbes – “adds to this exposure, but we find it troublesome that there is no mention within this evidence of any particular significance given to the orange color as a source-indicating feature of [Grypmat’s] goods.”

THE BOTTOM LINE: Single color marks remain relatively difficult to come by for use on things other than packaging. That does not mean, of course, that companies across industries – from shipping/logistics to fashion/luxury brands – will not continue to try, and in some cases, succeed.