Early this summer, Amazon filed one of the many thousands of patent applications that are currently pending in its name with the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (“USPTO”). Entitled, “Keyword determinations from conversational data,” the description of the invention that the $1.56 trillion tech behemoth is aiming to patent starts out like many other utility patent-centric intentions: with a computer-implemented method. As for what that particular method does, it “extract[s] from voice content produced by a user … topics of potential interest to a user, [which are] useful for purposes, such as targeted advertising and product recommendations.”

Enter: the “sniffer algorithm” – or better yet, “one or more” sniffer algorithms that not only sniff out topics that a speaker is potentially interested in but that also “attempt to identify trigger words in the voice content, which can indicate a level of interest of the user.” For example, as Amazon’s patent application states, “A keyword that is repeated multiple times in a conversation might be given assigned a higher priority than other keywords, tagged with a priority tag.” At the same time, “a keyword following a ‘strong’ trigger word, such as ‘love’ might be given a higher priority or weighting than for an intermediate trigger word such as ‘purchased.’”

In short, the listening algorithm can potentially determine what a consumer wants, just how much he/she wants it, and when.

Not exactly a new endeavor, the application is a “continuation of” similar applications filed by Amazon, such as one filed in August 2019 (now pat. no. 10,692,506), and before that, one that was filed in June 2017 (now pat. no. 10,373,620), and others, including one that dates back to September 2011 (now pat. no. 8,798,995), all of which have resulted in issued-patents for the tech titan.

But even before that, others were making use of sniffer algorithms, albeit largely outside of the retail space. Reflecting on the rise of “increasingly complex and machine-driven [financial] trading strategies,” Reuters reported back in 2007 that big banks and mighty hedge funds were using these algorithms “to sniff out algorithmic trading by others … in the hope that it will pick up trading opportunities – either working with or against the trading flow created by the rivals.”

Adding Context

Given that sniffer algorithms as a whole are not entirely novel tech, what is so special about Amazon’s renditions? According to Amazon, the existing technologies simply are not precise enough. To be exact, Seattle-based monolith states that “as users increasingly utilize electronic environments for a variety of different purposes, there is an increasing desire to target advertising and other content that is of relevance to those users,” which “conventional systems” simply do not do well enough.

The already-existing approaches to “determin[ing] items or topics that are of interest to the user … do not provide an optimal source of information,” per Amazon, because the information is “limited to topics or content that the user specifically searches for, or otherwise accesses,” i.e., information that consumers search for on Google or Amazon, or other sites, such as Zara or Zappos. And more than that, Amazon states that “there is little to no context” provided in connection with that information when it is gathered, thereby, giving rise to potentially useless data. For instance, Amazon asserts that “a user might search for a type of gift for another person that results in keywords for that type of gift being associated with the user, even if the user has no personal interest in that type of gift.”

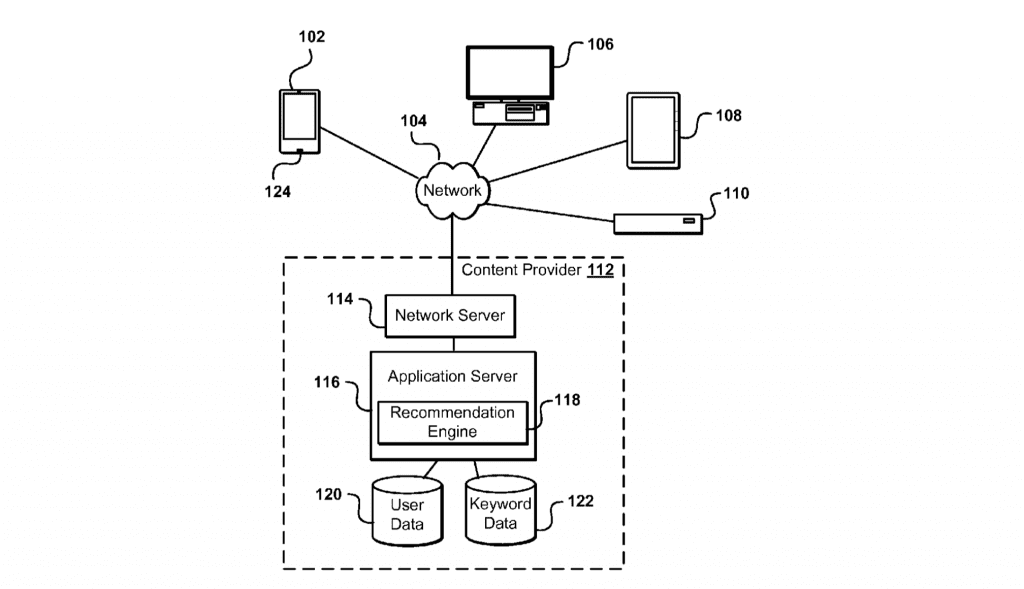

With that in mind, Amazon aims to go further with its own algorithmic endeavors to ensure that it captures “adjacent audio that can be analyzed, on [an Amazon] device or remotely, to attempt to determine one or more keywords associated with [the core] trigger word,” all of which can then be “stored and/or transmitted to an appropriate location accessible to entities, such as advertisers or content providers, who can use the keywords to attempt to select or customize content that is likely relevant to the user.”

Still yet, Amazon asserts that “in at least some embodiments, additional data” – such as “a timestamp or set of geographic coordinates,” the “location at which the keyword was identified,” and the identity of “the speaker of the keyword, a person associated with the keyword, [and/or] people nearby when the keyword was spoken,” etc. – can be stored for the relevant keywords, as well, in order to add context, and presumably, increase the accuracy of the ultimate attempts to target a user with ads or other content.

In terms of what the invention actually looks like when in action, Amazon provides a handful of examples – including ones that occur in real time – in its patent application. By way of a hypothetical, the company states that “if a user mentions a desire to travel to Paris while on a call, a recommendation for a book about Paris or an advertisement for travel site might be presented at the end of the call.”

Similarly, if the user mentions how much he/she “would like to go to a restaurant while on the phone, a recommendation might be sent while the user is still engaged in the conversation that enables the user to make a reservation at the restaurant, or provides a coupon or dining offer for that restaurant (or a related restaurant) during the call.” The targeting would happen in real time, “as providing such information after the call might be too late if the user makes other plans during the conversation.”

Reports predicted in 2018 when the sniffer algorithm patents first made headlines that the most obvious place for Amazon to deploy the technology is via its voice-activated Echo speakers, but the New York Times asserted that such capabilities “could be used on an array of devices, like [its] tablets and e-book readers,” as well. Fast forward two years, and Amazon’s latest application expands the scope, stating, “In at least some embodiments, a computing device, such as a smart phone or tablet computer, can actively listen to audio data for a user, such as may be monitored during a phone call or recorded when a user is within a detectable distance of the device.” (Also potentially on the table, Amazon’s new microphone-bearing Halo health band, which the Jeff Bezos-owned Washington Post recently called “the most invasive tech we have ever tested.”)

The same patent application also inserts the possibility of “facial recognition, or another such process, [which] can be used to identify a source of a particular portion of audio content,” particularly “if multiple users or persons are able to be identified as sources of audio.”

Are You Listening?

Amazon was adamant back in 2018 that it did not listen to customers’ conversations to target them with advertising or content. In a statement on Tuesday, a spokesman for the Jeff Bezos founded company told TFL, “We take privacy seriously and have built multiple layers of privacy into our Echo devices. Like many companies, we file a number of forward-looking patent applications that explore the full possibilities of new technology. Patents take multiple years to receive and do not necessarily reflect current developments to products and services.”

The latest rendition of Amazon’s enduring venture into sniffer applications (no. 20200388288) is pending before the USPTO, and was published for the world to see on December 10. As for whether the world will be eager to give Amazon permission to listen to their conversations in order to assist them in booking a trip to Paris, or nabbing a restaurant reservation, should Amazon ask, of course, is another matter entirely. It may seem unlikely on its face. However, given the widespread willingness of consumers across the globe to use “free” social media platforms and search engines like Google, which regularly collect and use consumer data, and continue to make such use despite such giants being the subject of repeated allegations of “spying,” it may not be entirely outlandish to think that some just might opt-in if/when the capabilities be expanded to them, thereby, agreeing to trade off some privacy for the convenience of even-easier shopping.

While Amazon has not (yet) formally announced its intent to implement the inventions at the heart of the “sniffer” patents, such techniques could very well be the future of shopping – including luxury shopping – and content distribution, too, which would explain the whispers of an impending Amazon, Condé Nast deal. That is, of course, if Amazon has its way.

* This article was updated to include an up to date comment from Amazon.