Amazon is in hot water – again – over how it is (allegedly) using third-party seller data in connection with its growing private label business. In a lengthy new report, Reuters claims that “thousands of pages of internal Amazon documents” show that despite previous rebuffs of accusations of using third-party seller data to boost the breadth and sales of its private label products, the e-commerce titan is engaged in “a systematic campaign of creating knockoffs and manipulating search results to boost its own product lines in India,” including by “secretly exploit[ing] internal data from Amazon.in to copy products sold by other companies, and then offer[ing] them on its platform” and “stok[ing] sales of Amazon private-brand products by rigging Amazon’s search results” so that the company’s products would appear first in search results.

The internal documents, such as emails, strategy papers and business plans, show that “Amazon employees studied proprietary data about other brands on Amazon.in, including detailed information about customer returns, [with] the aim to identify and target goods – described as ‘reference’ or ‘benchmark’ products – and ‘replicate’ them,” according to Reuters’ Aditya Kalra and Steve Stecklow.

In order to match the quality of the targeted products, Reuters reports that a 2016 document shows that Amazon employees that work on the Jeff Bezos-founded company’s own products, “planned to partner with the manufacturers of the products targeted for copying” in order to gain access to the “unique processes” employed by these manufacturers that ultimately “impact the end quality of the product.” The publication notes that “Amazon has been accused before by employees who worked on private-brand products of exploiting proprietary data from individual sellers to launch competing products and manipulating search results to increase sales of the company’s own goods.”

Among the targets of Amazon’s alleged copy-paste scheme, according to the new report? Shirt brand John Miller, whose offerings Amazon reportedly copied in near-exact detail, and then offered up on its own site. Other the brands/products that “Amazon employees planned to ‘benchmark,’” per Reuters, included John Players, an Indian menswear brand, and “‘Old Navy/GAP’ men’s shirts.” Although, the document “does not indicate whether the employees followed through.”

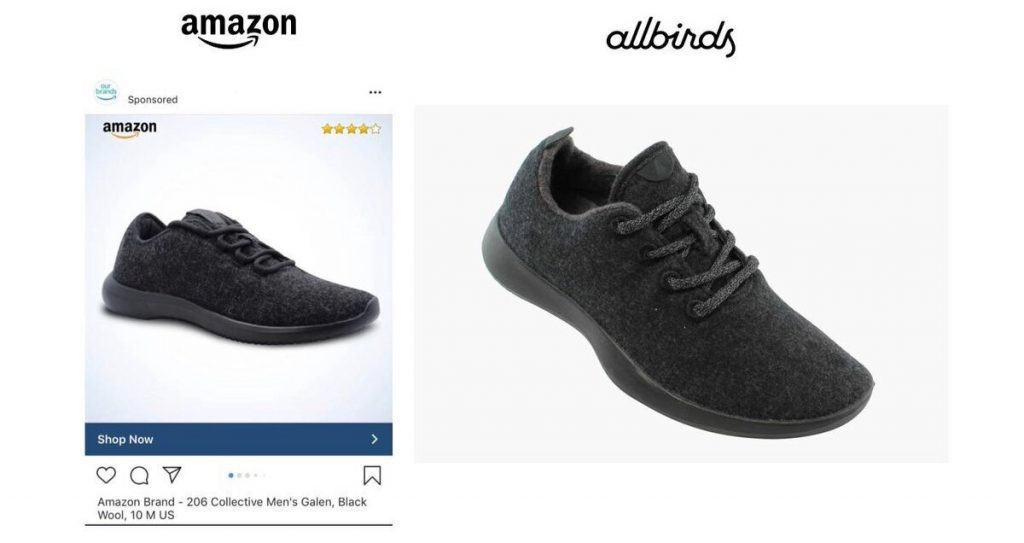

(Amazon has also faced pushback in the past in the form of call-outs and litigation for allegedly copying others’ offerings. The Seattle-based titan was sued for trademark infringement in 2018 by Seven For All Mankind for allegedly attempting to bank on the appeal and aesthetic of Seven’s Ella Moss label by way of its own private label, Ella Moon, which Seven argued is similar to Ella Moss “in sound, appearance, connotation and commercial impression.” It has also been on the receiving end of allegations from the likes of Allbirds, which accused Amazon of co-opting the design of its best-selling wool trainers.)

The practice of buying competitors’ – or wannabe competitors’ – wares, and then replicating them is hardly a novel one (or the biggest concern here), especially in the fashion industry. This accusation was at the heart of the since-settled lawsuit that California-based brand dbleudazzled filed against Khloe Kardashian and her brand Good American in May 2020, for instance. In addition to asserting claims of trade dress infringement, unfair competition, and fraud, dbleudazzled argued that between 2016 and 2017, Kardashian – by way of her team – “purchased and borrowed numerous pieces of [d.bleu.dazzled ] clothing, under the false pretense that the clothing items were for [the reality TV star’s] personal use.” However, instead of actually wearing the garments, as her team had led d.bleu.dazzled to believe would happen, Kardashian allegedly copied them for the clothing brand that she was secretly working on at the time and that she eventually launched in September 2016 to sweeping success.

Similarly, the notion of replicating hot-selling products for in-house lines has been in the wheelhouse of grocery store chains and departments stores for decades; so, again, this is not novel ground.

The biggest issue when it comes to Amazon, and what leads to anti-competition concerns, is not the alleged copying on its own, but the copying in connection with the sheer scale and robustness of the retail behemoth’s market power and ability to restrain competition. Taken together, Amazon’s alleged line-for-line copying, which is reportedly facilitated by its use of non-public data on third-party sellers, and its use of tactics on the backend to “direct customers to certain products” by way of search results – which is no small matter given that “an internal [Amazon] document in 2017 noted that more than half of users’ clicks on search results are for the products listed in the top eight” – has the potential to stifle the workings of other, smaller businesses. That is the potential problem.

In a report released in October 2020, the U.S. House Judiciary Subcommittee on Antitrust found that Amazon likely controls roughly 50 percent or more of the U.S. online retail market, and that it maintains monopoly power over third-party sellers on its marketplace, thereby, giving rise to “an inherent conflict of interest” – and “the incentive and ability to exploit” third-party sellers – in connection with its dual role of offering up its private label goods while also operating its third-party marketplace. (Amazon refuted the subcommittee’s findings.)

No stranger to claims of anti-competition, Amazon is being probed in the U.S., the Europe Union, and India, with U.S. Federal Trade Commission chair Lina Khan in particular taking a notably tough stance against the company in recent years. “It is third-party sellers who bear the initial costs and uncertainties when introducing new products; by merely spotting them, Amazon gets to sell products only once their success has been tested,” she wrote in 2017 paper, arguing that Amazon’s private-brand business raises issues when it comes to competition. “The anticompetitive implications here seem clear.”

Reuters expects that the “unfiltered insight the [recently revealed] documents offer into Amazon’s aggressive use of its market power could intensify the legal and regulatory pressure” that it is already facing in a number of countries.

Amazon pushed back against Reuters’ reporting, stating, “We believe these claims are factually incorrect and unsubstantiated.” The company states that it “strictly prohibits the use or sharing of non-public, seller-specific data for the benefit of any seller, including sellers of private brands,” and that it investigates reports of its employees violating that policy.