Deep Dives

Tiffany & Co. is courting controversy, and it is not mincing words in the process. The New York-headquartered jewelry stalwart very unambiguously announced late last month – via an ad campaign that swept Instagram and found a home on the sides of buildings and barricades in New York and Los Angeles – that its new products are, well … “Not Your Mother’s Tiffany.” The response to the campaign was as swift as it was fractured. Many longtime Tiffany & Co. customers expressed feelings of exclusion and frustration as a result of the new millennial and Gen-Z-centric push.

Some called the new positioning ageist; others characterized it as lazy, uninspired marketing – a “cop out” even. “There is nothing unique or special about claiming that a brand is contemporary,” branding and marketing consultant Leigh George stated. Even some young consumers – i.e., the ones being wooed – were put off by the tone. At the very same time, other consumers did not appear to be quite so dismayed, either approaching the campaign in a more light-hearted manner, maybe? – and/or simply not feeling targeted by the new “not your mother’s” message.

The campaign is one of the first major marketing moves since Tiffany & Co. assumed its position under the expansive ownership umbrella of LVMH in December 2020. And it comes as part of a new multi-prong, multi-year repositioning project being spearheaded by newly-installed EVP of Products and Communication Alexandre Arnault, 29, who is fresh from a successful revamp of German luggage brand Rimowa, and Tiffany’s new creative director Ruba Abu-Nimah. Ultimately, it is part of a “super aggressive change,” as former Amazon executive creative director Anthony Reeves put it, aimed at modernizing the brand that got its start almost two centuries ago and has been readily waning in relevance.

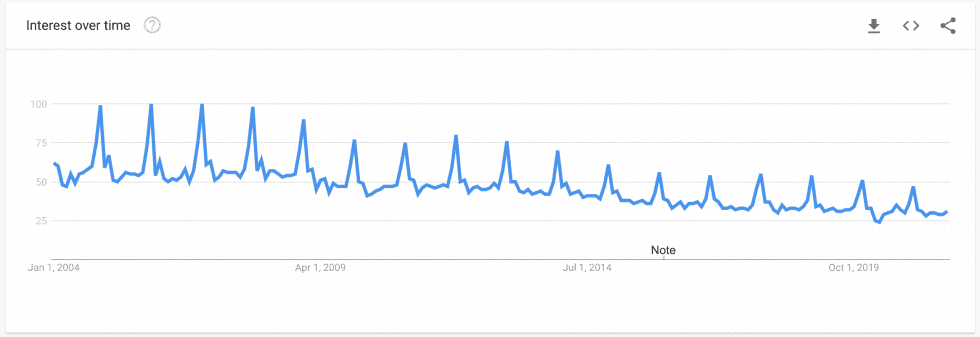

Declining Google search volume for “Tiffany & Co.”

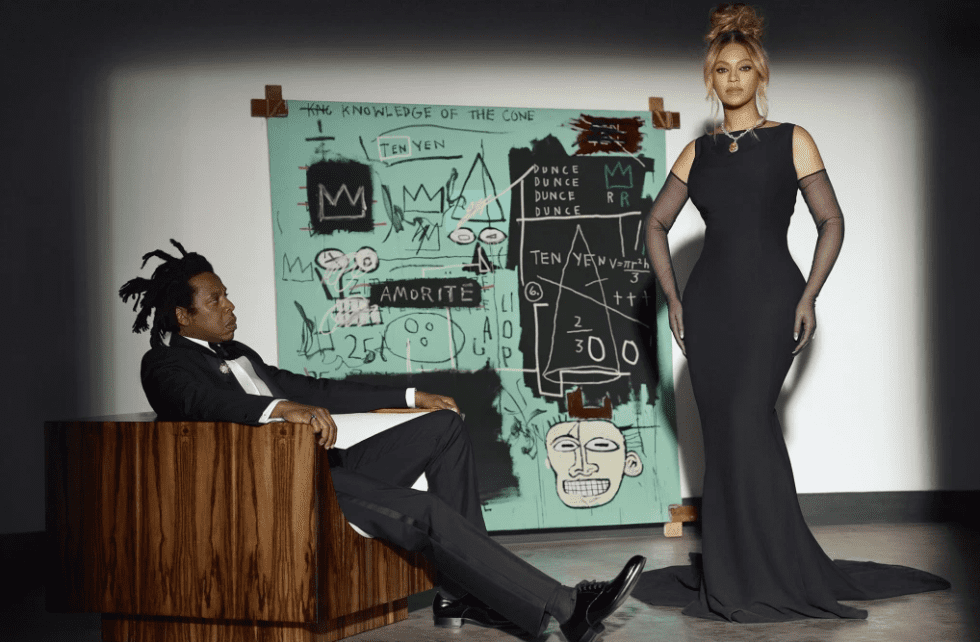

Just as “Not Your Mother’s Tiffany” is not a one-off revamp effort, the furor that followed from it is proving not to be exclusive to that series of ads. It has since been followed up by strong responses to the unveiling of another campaign this week, which features new brand ambassadors Jay-Z and Beyonce posed in front of Basquiat’s Tiffany blue-hued “Equals Pi” artwork. (More about the value of Tiffany blue here.) To put the pushback against that ad in nutshell, one Twitter user questioned, “Is it me or is a couple billionaires in Basquiat drag for Tiffany’s not the best look ever?”

Meanwhile, others pointed to the potentially questionable roots of the iconic 128-carat yellow Tiffany Diamond that is draped around Beyonce’s neck in the new campaign.

Looking beyond the specific instances of social media-centric havoc that Tiffany & Co. is currently wreaking thanks to the earliest stages of its revamp, the result has been the same: Tiffany is becoming part of the conversation. From an eye-balls perspective, Google searches for “Tiffany” rose significantly on July 12, amid the roll out of the “Not Your Mother’s Tiffany” campaign, indicating consumer attention – and interest. On August 23, the confluence of Beyonce, Jay-Z, Basquiat, and Tiffany was trending heavily on Twitter.

While the brand protectionists among us will likely lean towards alarmed due to the onset of sweeping consumer backlash and talk of “blood diamonds,” LVMH is no stranger to controversy. The Paris-based group trades in big-money ads and over-the-top runway spectacles, and weathers media storms from time to time all in furtherance of its goal of achieving enduring relevance and ultimately, bagging super-sized revenues in a relatively high-turnover business. (To put its marketing endeavors – and the importance that it places on them – into perspective, LVMH spent $6.3 billion, or 12% of its annual revenues, on marketing in 2018.)

This is not your average brand’s balance sheet, after all. LVMH, which holds the title of the largest luxury goods group in the world, is in the business of building multi-billion-dollar brands – or “star” brands, as LVMH chairman and CEO Bernard Arnault called them in an interview back in 2001. Much has changed since 2001, but at least one thing has not. LVMH is still chasing big-picture revenue growth. It banked $52.44 billion in revenue in 2020, down from its pre-pandemic $63.05 billion in sales for 2019.

The Tiffany-centric backlash fits neatly within the demands of the modern attention economy, one that requires relevance and that places publicity on a pedestal. In this way, the new-found attention to Tiffany is a good thing, even if it is not glowing. “Stepping back from the fray, when is the last time so many people have been talking about Tiffany?,” e-commerce veteran and “No Best Practices” newsletter creator Alex Greifeld asked this week. “In a fractured media landscape,” she says, “the only way to get broad awareness is to piss (some) people off.”

LVMH knows this move. It is more or less what LVMH did back in 1997 when it put Marc Jacobs in the top creative spot at Louis Vuitton, several years after the then-disgraced designer was very publicly fired from his role at Perry Ellis after showing that now-infamous grunge collection, with its cheap-looking Goodwill-inspired wares and luxury-level prices. But what was one clean-cut brand’s liability was an attention-angling conglomerate’s golden ticket.

“Mr. Jacobs’s ability to get publicity, instead of selling frocks, wasn’t valued by Perry Ellis executives, who dropped the collection,” and Jacobs right with it, Amy Spindler wrote for the New York Times in 1997. It was, however, just the currency that Mr. Arnault was looking for in connection with his plans to launch Louis Vuitton’s first-ever foray into ready-to-wear. “There’s no doubt,” she stated, “how much that publicity is valued at Vuitton.” And it worked: by 2000, Louis Vuitton had 40% growth in sales. “That makes the brand a superstar, no?,” Arnault quipped at the time.

While the younger Mr. Arnault is not starting from scratch with the Tiffany & Co. revamp (quite the opposite, given the brand’s 184 years of history) in the same way that Jacobs was tasked with building a ready-to-wear brand for the first time, there are high stakes, nonetheless; LVMH paid an eye-watering $15.8 billion to acquire Tiffany that it needs to make good on, and competition is heating up in the hard luxury space. And more fundamentally, despite its storied history and “iconic” stature, Tiffany & Co. is a staid brand in need of a serious reinvention in terms to product and marketing in order to attract younger consumers.

So, shortly after the dust settled on the Tiffany acquisition (and corresponding legal battles), LVMH ushered out the Tiffany’s team, and brought in its own people, namely, former Louis Vuitton senior executive Anthony Ledru as CEO, the younger Mr. Arnault, and Louis Vuitton chairman Michel Burke, who is also the chairman of Tiffany. With them has come an aggressive – and undoubtedly polarizing – focus on Millennials and Gen-Zs, i.e., the ones who contributed a whopping 100% to total luxury market growth in 2018, according to Bain & Company, and together will represent nearly 55% of the marketby 2025.

As for the risk of Tiffany losing touch with its long-time customers in furtherance of its quest to woo pretty-young-things, it might seem sizable, including because of the spending power of older consumers. Not only is the total spending power of individuals that are 65 and older increasing on a global basis; it is expected to rise to $14 trillion within the next decade, up from roughly $8.4 trillion in 2020, Bloomberg previously stated that the world’s emergence from the COVID-19 pandemic is likely to “unleash a wave of spending by older consumers,” with money managers pointing to “huge pent-up demand from wealthy seniors” for things like luxury goods.

Couple this with the fact that consumers seem to be more clued-in to the workings of brands that they follow and more sensitive to brand messaging than ever before, and the brand backlash that Tiffany is facing appears to be a recipe for disaster. Yet, that is not likely to be the outcome of this budding success story.

As Tiffany & Co. knows, consumers appear to be more susceptible to – and willing to engage in – outrage against brands than in the past, but their attention spans are also remarkably short. Look no further than the trending topics on Twitter. Backlash against the Tiffany & Co. campaign with Beyonce, the alleged “blood diamond,” and the Basquiat was trending on Tuesday, and it was almost entirely old news by Wednesday. Sure, people were still tweeting about it, including about the overblown “never before seen” language that has been peddled in connection with the Basquiat work despite the painting appearing in at least one editorial and changing hands at least twice via Sotheby’s auctions.

However, by August 24, the negative repercussions had largely been replaced by news of Rolling Stones drummer Charlie Watts’ death, the latest attempt at a GameStop short squeeze, and the latest intel coming out of Afghanistan, at least according to Twitter data. In other words, the bad buzz has died down significantly, but the potential relevance for Tiffany as a brand worth paying attention will likely linger in the minds of consumers, even if just subconsciously.

Save for some really extreme scenarios, looking to expand beyond Tiffany’s nearly 200-year-old DNA in this way is not going to hurt it. Yet, as we discussed here, companies often “completely overthink things on the reputation front,” and thus, fail to take risks for fear of diluting or tarnishing the brand as it currently exists – even if that brand is in need to a major overhaul. By taking a purely protectionist stance, companies neglect the fact that “brands are far more robust than we like to give them credit for,” and in the long run, many consumers may not really care about things like brand image or values.

Tiffany, it seems, is not standing still, and instead, is acknowledging the fact that the most sizable risk is less likely to come in the form of temporarily alienating unamused or even angry consumers. The real risk is if Tiffany does nothing at all and continues to rely on its past to attract consumers in the present – and in the future.

The Bottom Line: Social media chatter aside, LVMH is currently doing what it does best, and in all likelihood, this is what the path to doubling the $4.4 billion in revenue that Tiffany & Co. generated in 2019 over the next five year looks like. This and an array of new product, of course.