Deep Dives

In October, eBay announced that it will authenticate high-end timepieces in the UK as part of a larger roll out of services aimed at giving consumers confidence in buying luxury-level products, including handbags and coveted sneakers, from its sweeping marketplace. The news was swiftly followed up by an announcement that Poshmark had acquired authentication platform Suede One in order to “scale [its] authentication capabilities and accelerate momentum in high-growth secondhand categories.” The two companies are among the latest to beef up their efforts to distinguish between counterfeit and real products in the burgeoning secondary market.

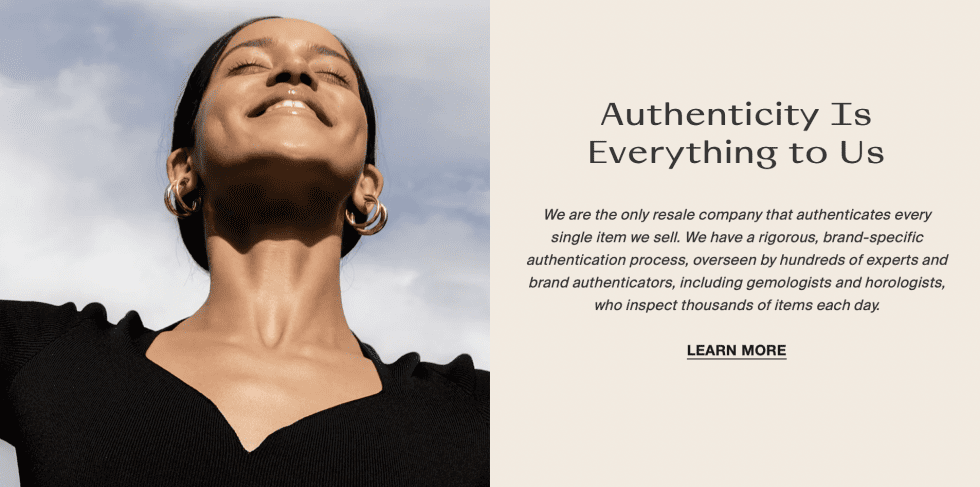

Driving the increased emphasis on authentication in the resale market, one that is on track to reach $77 billion in sales by 2025 (per ThredUp)? It is a major competitive advantage for platforms to be able to guarantee that consumers will get the real thing from them, especially as the secondary market becomes increasingly more crowded. As such, companies are putting authentication at their heart of the models in order to differentiate themselves from others and to boost their value offering to consumers. (This is something that The RealReal, for example, has been doing from the outset, as most obviously indicated by its branding.)

Issues With Authentication

While offering up authentication guarantees is undoubtedly a way to win over buyers in the resale segment, it is worth considering the balance at play when it comes to making such representations, and whether resale marketplaces are setting themselves up for legal issues in connection with their specific attempts to gain the trust of consumers. To some extent, it seems like they might be.

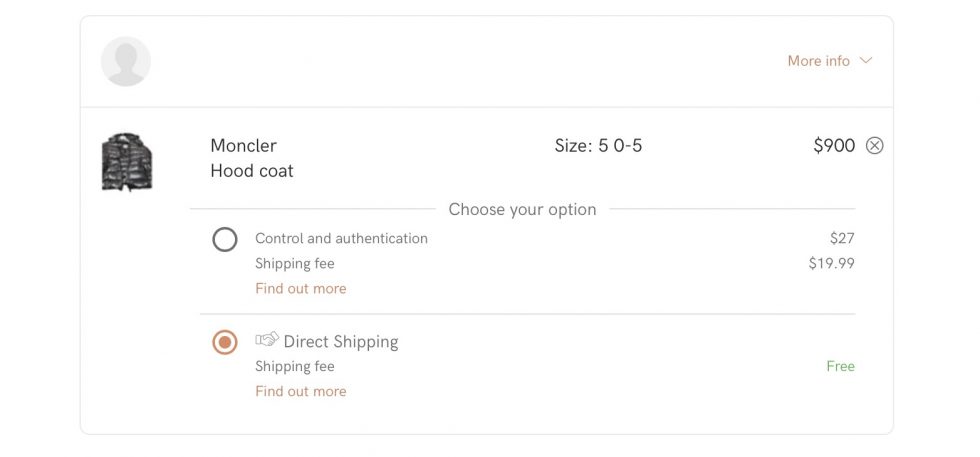

A big part of the issue here is that it is a double-edged sword for resale companies to take possession of pre-owned goods from consumers in order to authenticate them. On one hand, as we have established, the authenticity guarantees that result from such inspections enable resale players to set themselves apart from others (as not all companies provide authentication services and corresponding authenticity guarantees; Vestiaire, for example, gives buyers the option to have an item authenticated).

On the other hand … taking possession of products may expose resale companies to heightened liability should products turn out to be fakes. This is because of the increased level of control that a company assumes when it inserts itself into the equation by taking possession of the products – and evaluating their authenticity – as opposed to simply acting as a middleman.

Image via Vestiaire showing optional authentication

Image via Vestiaire showing optional authentication

At the heart of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit’s 2010 decision in Tiffany v. eBay – and a big part of why Tiffany avoided contributory trademark infringement liability in connection with the sale of counterfeit Tiffany products on its platform – was that sales were made between third-party sellers and buyers, making eBay an arms-length marketplace operator with less control over the goods than the actual seller. The appeals court held that knowledge of specific instances of infringement – as opposed to just “general knowledge” – was necessary in order to hold the proprietor of an online marketplace liable, and Tiffany didn’t have that level of knowledge.

In the still-ongoing trademark case that Chanel filed against The RealReal (TRR”), the court acknowledged this, stating in April 2020 in response to TRR’s motion for summary judgment that the reseller may be liable for infringement in connection with the sale of allegedly counterfeit goods on its site. While TRR does not take title to the merchandise that it sells, it does take physical possession of the merchandise, and “retain[s] the power to reject for sale, set prices, and create marketing for goods,” according to the court. In other words, “Unlike eBay, it is more than a platform for the sale of goods by vendors.”

With the benefits that come with TRR’s model – including its ability to give consumers certainty about the authenticity of the goods at play – also come downsides. Namely, SDNY Judge Vernon Broderick held that TRR “must bear the corresponding burden of the potential liability stemming from its ‘sale, offering for sale, distribution, [and] advertising of’ the goods in the market it has created.”

This seems to suggest that from a legal perspective, resellers that take an arms-length approach may be better off. The potential work-around here might be authentication by way of a third-party service provider that takes possession of the goods, and indemnification of the resale company by that third party in the case of issues.

The second issue here comes in connection with what brands are saying about authentication – and who can really do it. TRR’s claim that it can authenticate Chanel goods has been a sticking point for the French fashion brand, which has argued in the case that “no reseller may describe a Chanel product as authentic because ‘[o]nly Chanel itself can know what is genuine Chanel.”

This sentiment is not actually unique to Chanel. On its website, Audemars Piguet says that “the authenticity of an AP watch can only be confirmed after examining it in our workshops.” Hermès states the “only way to guarantee the authenticity of an Hermès product is by making your purchase through our official website Hermes.com, at an Hermès store or through an authorized distributor.” Rolex contends that its watches “should be only purchased from Official Rolex Retailers, who are authorized to sell and maintain Rolex watches,” as they can “guarantee the authenticity of each and every part of your Rolex.” And the list goes on

Language from Rolex’s website

With this relatively uniform messaging in mind, there is a (good) chance that such explicit assertions by resellers about their ability to ensure authenticity will ruffle brands’ feathers. Moreover, it is not difficult to imagine the potential for brands to lodge false advertising claims if/when counterfeit or otherwise infringing goods are found to be in play. (It is worth noting that at least some brands are increasingly looking to widen the net when it comes to defining counterfeit/infringing goods to include those that have undergone modifications.)

TRR has pushed back against Chanel’s attempt to claim the exclusive title of abled authenticator of Chanel goods. Specifically, the reseller has lodged anticompetition counterclaims against the brand, arguing that Chanel is engaging in an “overarching anticompetitive scheme” to “impair the growth and development of innovative resale rivals like TRR that threaten Chanel’s dominance.” Part of that scheme is Chanel’s “nonsensical” claim about others’ abilities to authenticate its products, which TRR argues could make it “impossible for all secondary dealers to do business.”

(TRR also alleges that Chanel is targeting secondary market competitors (save for Farfetch) with “bad faith” lawsuits, while also entering into “anticompetitive” agreements with a handful of publications like New York Magazine and WWD, and retailers, such as Saks and Neiman Marcus, to stop them from doing business with TRR, thereby, stunting its growth.)

This deep dive is arguably too long at this point, and so, I will save an in-depth discussion about the viability of TRR’s anticompetition claims against Chanel for another subscriber-exclusive article. What I will include for the time being is part of Chanel’s response to such monopolization claims, namely its argument that TRR has not actually established that Chanel has a “dominant market share” in the purported markets at issue: the “top tier investment grade” and “hold-value” handbag markets.

The market share figures that TRR sets out – which range from 30% to 50% – do not “establish an actual monopolization claim,” per Chanel, which asserted in November 2020 that case law puts the “minimum market share … between 70% and 80% in order to succeed on a claim of monopolization.” Beyond that, Chanel also argued that it is “entirely implausible that Chanel possesses even a 30% market share in a market that includes not only every seller of the relevant handbags … but also every reseller of such handbags nationwide.” This is significant, according to Chanel, “as in order to plead a claim for actual monopolization under Section 2 of the Sherman Act, TRR must plausibly allege that Chanel has ‘monopoly power’ in the relevant market.”

There will be more to come on this soon. In the meantime, Shein’s owner Zoetop made an anticompetition argument in response to the trademark lawsuit that AirWair filed against it, claiming that, among other things, the Dr. Martens owner has “attempted to use its purported trademarks and trade dress in an overly broad manner for anticompetitive purposes to drive competitors out of the market.”