The economic fall-out from COVID-19 is significant and sweeping, with companies like J. Crew and Neiman Marcus filing for bankruptcy, and individuals being laid off en masse in light of non-essential business closures and shelter-in-place mandates. The recovery will need to address widespread unemployment and a rise in faltering businesses as a priority, while reducing the mountain of national debt that has accumulated in recent months.

Given “the economic storm” that has been caused by the pandemic, “every occupant of every C-suite is trying to figure out what they are willing to throw overboard” in order to cut costs. Reflecting on a potential halt to companies’ sustainability initiatives, the Wall Street Journal reported in May that “businesses that were planning to help save the world are now simply saving themselves,” with many putting eco-centric efforts on the back burner for the time being in much the same way as they did when the financial crisis hit in 2008.

But while many companies are expected to cut down on funds earmarked for sustainability endeavors, the circular economy – an economic system aimed at eliminating waste by extending the lifespan of resources and a key concept in the push towards sustainability – very well may offer part of the solution for lasting recovery.

What is wrong with our current model?

The circular economy is best understood by first looking at the linear economic model that has dominated industrial activity since the 19th century: Resources are extracted to produce goods, which are then distributed to markets, consumed and thrown away at the end of their useful life. In short it is a “Take – Make – Waste” model. This system worked well in a world of less than one billion inhabitants, in which resources were cheap and abundant, and waste was not a particular problem.

But the world has changed. With 7 billion people on the planet – and rising – all expecting the standard of living we have grown accustomed to in the West, our demand on resources has grown, increasing pressures on non-renewable resources and waste management.

According to the United Nations’ 2017 Resource Panel Report, around 90 billion tons of natural resources are extracted every year to make the goods that we consume. This equates to more than 12 tons per year for every person on the planet. Based on current trends, that number is likely to double by 2050, and as of now, only 10 percent of these resources are recovered according to Circle Economy.

What is the circular economy?

So, what is the circular economy exactly? According to the Ellen Macarthur Foundation, a circular economy is an industrial system that is restorative or regenerative by design. It is underpinned by three principles: (1) design out waste and pollutionby changing our mindset to view waste as a design flaw; (2) keep products and materials in useby designing products and components so they can be reused, repaired and remanufactured, ensuring no materials end up in landfill; and (3) regenerate natural systemsby aiming to enhance natural resources by returning valuable nutrients to the soil and other ecosystems.

In other words, the circular economy is about much more than recycling. It is about maintaining economic value in production processes for as long as possible. This includes reducing the demand for high-resource products, and ensuring that products last longer, and are easily reparable and upgradeable. After all, something must be wrong when it costs less to buy a new TV than it costs to repair your old one.

One of the most interesting aspects of the circular economy is the largescale transition by companies from being product-providers to being service-providers. Some of the biggest success stories over the past decade have come not from companies that make things but ones that provide consumers with services.

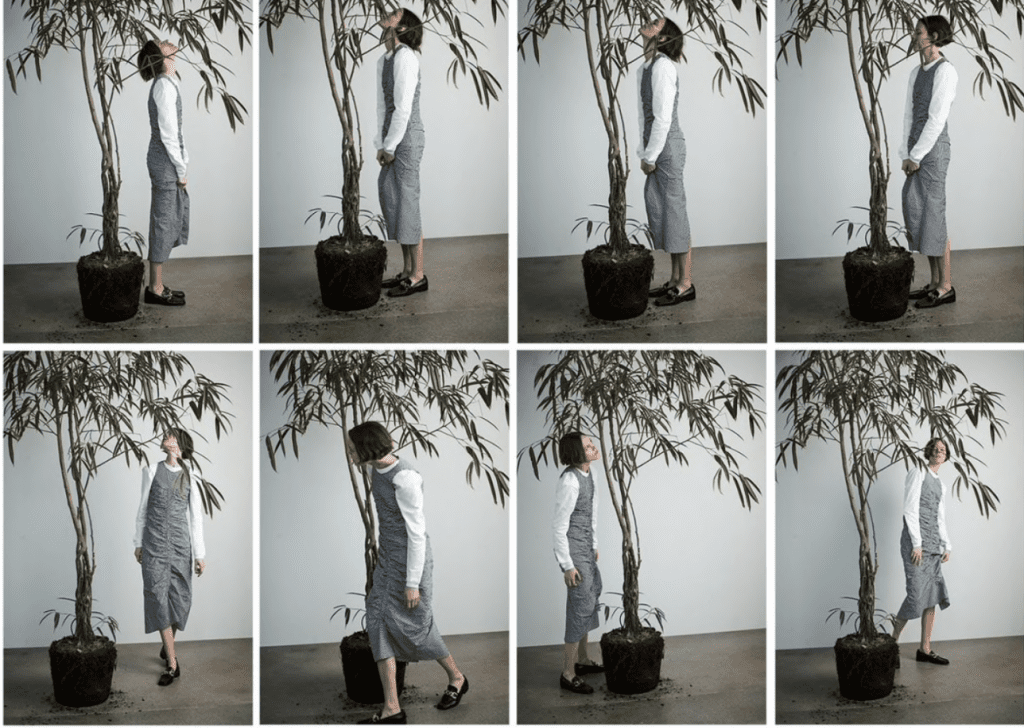

Examples of this include Uber, which enabled consumers to get from point A to point B without owning a car; AirBnB, which banks on property owners’ excess capacity rather than building new capacity of its own; and Rent the Runway, which provides consumers with the opportunity to rent clothing, as opposed to producing new garments.

The sharing economy – and a rising sharing mentality (why buy when you can borrow?) – is also moving us towards a more circular economy.

COVID and the circular economy

What does this have to do with COVID-19 recovery? While the crisis has increased some waste streams in single-use, disposable items, there is growing consensus that the circular economy can support recovery plans in four key areas:

Reducing supply-chain risks: One of the consequences of the crisis is that our confidence in global supply-chains has diminished. In a world that can shut down international transport in a matter of weeks, an over-reliance on global supply-chains is a significant risk to business continuity. Nations and businesses will seek to build greater supply-chain resilience by increasing the local purchase of raw materials, many of which can already be found in existing products that have reached the end of their useful life.

Alleviating cost pressures: As businesses and households are struggling financially as a result of the crisis, we will have to prioritize our purchases. This means that ‘second-life’ products will become much more attractive as they can meet our needs at lower cost. For businesses there are already a number of materials marketplaces, which allow for industrial reuse of raw materials, while at the consumer end, the Re-Tuna recycling mall in the Swedish town of Eskilstuna delivers that “shopping-mall buzz” while only selling recycled goods, supporting by Swedish tax law which reduces VAT on used products. Online platforms like eBay have of course capitalized on this for many years.

Creating jobs: According to the European Union’s Green Deal, “a more circular economy has the potential to bring production home, eliminate foreign dependencies and create hundreds of thousands of new jobs.” The EU aims to create 1 million new green jobs.

Generate growth: An increasing number of studies have highlighted the wider macro-economic benefits of the circular economy, which is one of the reasons it is part of the EU’s recovery plan. The World Economic Forum, for instance. estimates that material savings of over $1 trillion can be achieved from reuse, recycling and upcycling. The Ellen MacArthur Foundation estimates that circularity in manufacturing could yield net material cost savings of $630 billion per year in the EU, alone. And according to London’s Circular Economy Route Map, a circular economy in London could generate up to £7 billion in net benefit per annum by 2036.

What can businesses do?

The case for action is strong. Taking into account recent World Economic Forum and Boston Consulting Group reports, companies are encouraged to engage with external stakeholders, as no single business can do this alone, and to make the business case for circularity, namely by identifying and quantifying the opportunities that rethinking products, business models, processes and material flows can bring.

Additionally companies can immediately begin to define and measure circularity-centric goals, and place an emphasis on transparency and accountability. They are also encouraged to set up reverse networks for products and components to enable value to flow both ways, not just from raw materials to consumption, and to reorganize and streamline pure material flows to ensure that material flows are visible and that their value-chain identifies and utilizes sources of value.

Finally, companies should aim to innovate their business models on the demand side. Innovation is critical and circular innovation has many dimensions – from product design and supply-chain logistics to production processes and business models.

Oliver Dudok Van Heel is the Head of Client Sustainability and Environment at Freshfields Bruckhaus Deringer LLP. (Edits/additions courtesy of TFL)