In a marked push to appear more authentic in the eyes of consumers in connection with their advertising efforts, fashion and beauty giants, and lifestyle brands, alike, have looked to user-generated content to promote their products in recent years. Joining the likes of buzzy startups, established names in beauty, and companies like GoPro, the Walt Disney Company decided to do the same thing, as well, and so, it tweeted its 1.3 million followers this week, and invited them to celebrate the annual Star Wars-centric day, May 4th. In a tweet on Monday, Disney’s subscription arm, Plus, called on users to “Celebrate the Saga! Reply with your favorite #StarWars memory and you may see it somewhere special on #MayThe4th.”

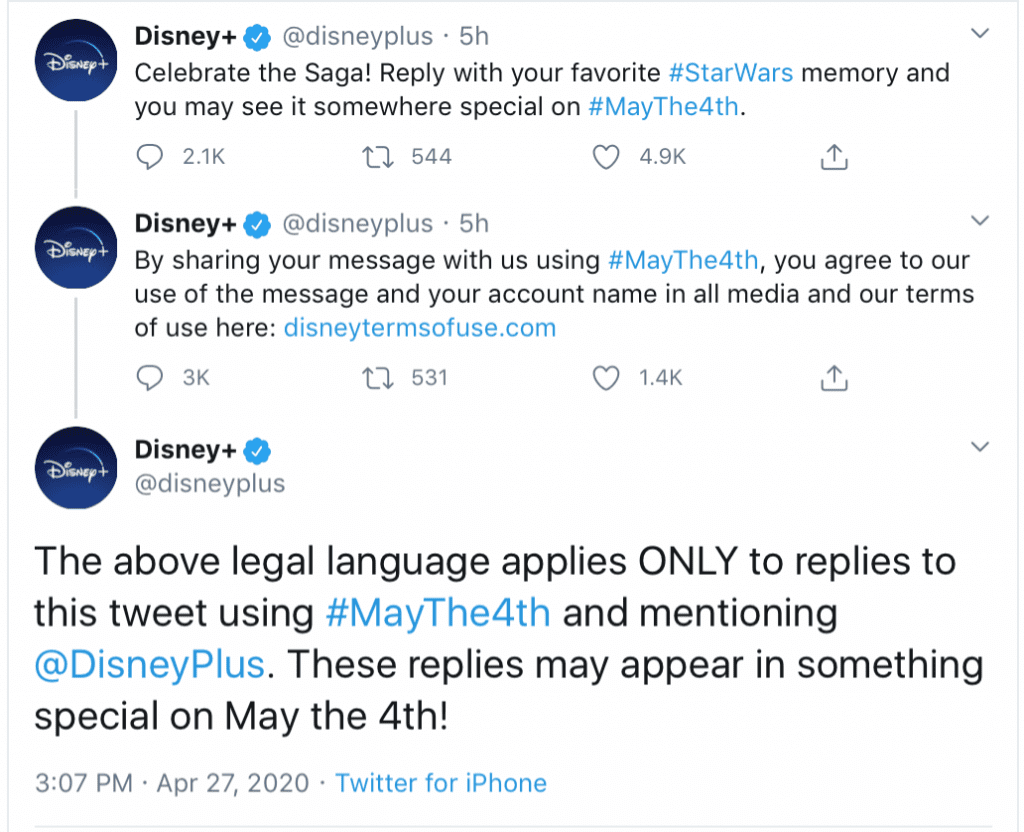

Disney was seemingly hoping to prompt responses about happy fans’ experiences with the Star Wars franchise and maybe elicit some nostalgia-soaked marketing gold in connection with the George Lucas-created series of films. That is largely not what happened, as its message took on a legal element in light of a follow up tweet, in which Disney Plus shared an important caveat: “By sharing your message with us using #MayThe4th, you agree to our use of the message and your account name in all media and our terms of use.”

In short, the media giant is claiming the right to use – and monetize (via sublicensing) – any messages and/or imagery shared with that hashtag. In its tweet, it alerted users to its 6,700-plus word Terms, which state, in part, that when users “communicate, submit, upload or otherwise make available text, chats, images, audio, video, contest entries or other content” to Disney, they are granting the company “a non-exclusive, sublicensable, irrevocable and royalty-free worldwide license.”

Based on that “license,” Disney says it can “use, reproduce, transmit, print, publish, publicly display, exhibit, distribute, redistribute, copy, index, comment on, modify, transform, adapt, translate, create derivative works based upon, publicly perform, publicly communicate, make available, and otherwise exploit [that content], in whole or in part, in all media formats and channels … without further notice to you, without attribution (to the extent this is not contrary to mandatory provisions of applicable law), and without the requirement of permission from or payment to you or any other person or entity.”

The backlash was swift, and largely came in the form of tweets, such as “#MayThe4th be with your creepy efforts to monetize every aspect of the fan experience,” “Disney is a vampire that steals culture and replaces it with copyright,” and “My favorite Star Wars memory would have to be the time Disney tried to lay legal claim to every tweet on Twitter that used a particular hashtag,” etc.).

In response to such criticism, Disney walked back – a bit – on its initial statement, asserting a few hours later in another follow up tweet: “The above legal language applies ONLY to replies to this tweet using #MayThe4th and mentioning @DisneyPlus. These replies may appear in something special on May the 4th!”

Given brands’ quest to adopt user-generated content in an effort to simultaneously showcase their products, celebrate fans, and drive revenue, it is not surprising that Disney is not the first to rely on such sweeping (and potentially unenforceable) claims in connection with others’ use of a hashtag. In 2017, NYX Cosmetics, for instance, made headlines (on this website) when it enacted – and began relying upon – a provision in its own lengthy terms and conditions that essentially stated that when an Instagram user adds the hashtag “#nyxcosmetics” to any of their photo captions on Instagram, they are granting NYX the right to “alter,” “edit” and “re-post” that content without their authorization and without compensation.

NYX stated on its own Instagram account at the time, “As stated in Instagram’s privacy policy, once you have shared user content or made it public, that user content may be re-shared by others.” As such, “NYX Professional Makeup shall have the right to use any content submitted by user using a NYX Professional Makeup-created hashtag and shall have the right without limitation to edit, stylize, crop, digitize or alter this content and use your content in accordance with the rights you grant under these terms and our general NYX Professional Makeup website terms and conditions.”

In hindsight, NYX’s message seems to have foreshadowed (to a certain extent) the recent decision from Judge Kimba Wood of the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of New York (“SDNY”), who held that media outlet Mashable did not infringe photographer Stephanie Sinclair’s copyright in a photo that it embedded into one of its articles without her authorization because she had granted Instagram “a non-exclusive, fully paid and royalty-free, transferable, sub-licensable, worldwide license” to use the content that she published on her publicly-accessible account when she signed up use the photo-sharing app.

According to Judge Wood’s decision, because Sinclair granted Instagram the right to use and license the photo to others when she joined (and by virtue of maintaining a public account), Mashable’s act of embedding the image into its article using Instagram’s API falls within such a scenario, thereby, removing the need for Mashable to get a license from Sinclair (because it already had one from Instagram).

This appears to be – more or less – what NYX was getting at with its own message.

As for whether that non-infringement principle extends to Disney and Twitter, the same boiler plate language – i.e., Twitter users grant the app “a worldwide, non-exclusive, royalty-free license (with the right to sublicense)” purely as a result of “submitting, posting or displaying Content on or through the [app]” – is certainly at play. And it would not be difficult to see how the SDNY’s decision could easily translate from a Instagram-specific context to Twitter, assuming, of course, that the tweets at issue are reproduced using one of Twitter’s API and the content does not consist of a screenshot that Disney took of the tweet that is then republished.

Assuming that Disney does not plan to embed the #MayThe4th tweets that it aims to use, which is more likely the case, this instance gives rise to a whole slew of other legal issues, including ones that center on the enforceability of Disney’s attempted rights-grab given that: #MayThe4th is a commonly used hashtag that at least some Star Wars fans will use on May 4th without intending to participate in Disney’s Twitter celebration, and also, without seeing Disney’s terms tweet or its lengthy terms of service (and the corresponding intellectual property-related license claims) beforehand. (Disney’s hypothetical case also probably is not helped by the fact that its terms in connection with the #MayThe4th “celebration” are contained in a separate, subsequent tweet that Twitter users could easily miss if only the initial tweet, for instance, is retweeted by an account they follow).

More generally, this instance seems to shed light on where the future of clickwrap licensing is going after first coming about in the form shrink-wrap licensing – a somewhat contested type of license (as indicated by case like Specht v. Netscape Communications Corp.) that becomes effective the moment a user takes the shrink-wrap off of a physical product, such as computer software – and evolving with the rise of digital technologies like social media platforms. The less readily-accepted browsewrap agreements – which do not require the user to take such an affirmative action, such as clicking “I agree,” and instead, binds a user (typically to the terms of use for the website) simply as a result of him/her browsing the website – fall in here, as well.

But maybe the biggest takeaway here is not necessarily legal in nature at all. It is a lesson for marketing (and also legal) departments across the board about how to effectively engage with fans and prompt them to share content of their down, while also alerting them of the necessary legal terms. Based on the feedback from the very consumers that it was looking to engage with, Disney did not achieve either of those elements terribly well.