Deep Dives

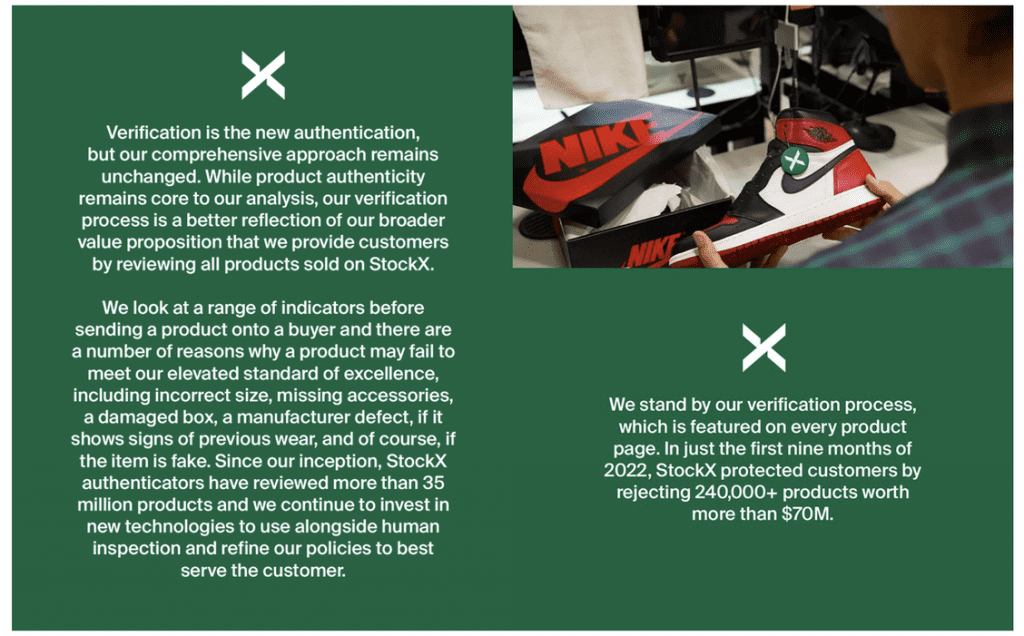

StockX has garnered attention on social media this month in connection with some changes to the marketing of its authentication warranties. In a statement on November 14, the Detroit-based sneaker and fashion resale platform revealed that it “updated the name of [its] verification process” – moving away from labeling the goods on its platform as “Verified Authentic” and “100% Authentic” in favor of the new “StockX Verified” label. Shedding some light on the new language, the company said, “StockX Verified is our own designation and not endorsed by any brands sold on StockX.” (The resale platform also assured consumers that nothing in the actual authentication/verification process is different.)

The name-change is an interesting one for at least a couple of reasons. First, it comes as StockX is embroiled in an NFT-centric lawsuit with Nike, with the Swoosh accusing StockX of trademark infringement, counterfeiting, and false advertising, among other claims, and asserting in an amended complaint in May that by peddling products as “100% Verified Authentic,” StockX is looking to trade on the reputation and appeal of the Nike brand. That labeling is also an issue, per Nike, as “StockX has been and is currently dealing in counterfeit Nike goods, which renders [its] ‘100% Verified Authentic’ claims false and/or misleading.”

StockX’s move away from “100% Authentic” is also noteworthy, as it is not the first time a reseller has made such a change. At some point between 2020 and 2021 or so, The RealReal (“TRR”) quietly dropped references to the pre-owned products on its site as being “100% Authentic.” The luxury resale player’s shift in language followed from a couple of hard-hitting CNBC reports in 2019 that detailed its alleged offering of counterfeit goods; the articles (and subsequent hits to TRR’s Nasdaq-traded stock price) prompted a string of stock-drop lawsuits for the company and in at least one case, its directors and board members.

TRR’s discontinuation of the “100% Authentic” warranty also came on the heels of Chanel filing a headline-making lawsuit against it in November 2018. In that case, which is still underway in the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of New York, Chanel is accusing TRR of selling counterfeit goods and engaging in “improper business practices” by “represent[ing] to consumers that it ‘ensure[s] that every item on TRR is 100% the real thing, thanks to our dedicated team of authentication experts.’” (The authenticity claims made by TRR are particularly problematic, according to Chanel, as while the reseller “purports to offer genuine and “100% authentic” products, including CHANEL-branded products, an investigation conducted by Chanel has revealed that [TRR] has advertised as genuine and authentic at least seven counterfeit Chanel handbags.”)

TRR’s discontinuation of the “100% Authentic” warranty also came on the heels of Chanel filing a headline-making lawsuit against it in November 2018. In that case, which is still underway in the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of New York, Chanel is accusing TRR of selling counterfeit goods and engaging in “improper business practices” by “represent[ing] to consumers that it ‘ensure[s] that every item on TRR is 100% the real thing, thanks to our dedicated team of authentication experts.’” (The authenticity claims made by TRR are particularly problematic, according to Chanel, as while the reseller “purports to offer genuine and “100% authentic” products, including CHANEL-branded products, an investigation conducted by Chanel has revealed that [TRR] has advertised as genuine and authentic at least seven counterfeit Chanel handbags.”)

Nike stance when it comes to authentication and in particular, how others are able to market themselves on this front, is not necessarily unique. A noteworthy number of luxury brands have taken strong positions; in its suit against TRR, for example, Chanel has argued that “the only way for consumers to absolutely ensure that they are, in fact, receiving genuine CHANEL products is to purchase such goods from Chanel or from an authorized retailer of Chanel.” Meanwhile, Audemars Piguet states on its website that the authenticity of an AP watch “can only be confirmed after examining it in our workshops.”

Other luxury brands are quite a bit less explicit, with Rolex stating that, “New and genuine Rolex watches are exclusively sold by Official Rolex Retailers, who warrant the authenticity of your Rolex.” With the “necessary skill, training, know-how and special equipment on site, [Official Rolex Retailers] guarantee the authenticity of each and every part of your Rolex, and can ensure its reliability over time,” the Swiss watchmaker further states. The same goes for Hermès, whose website reads: “The only way to guarantee the authenticity of an Hermès product is by making your purchase through our official website Hermes.com, at an Hermès store, or through an authorized distributor.”

The Macro View

The Macro ViewFrom a bigger picture perspective, the evolving language being used by the likes of TRR and StockX seems to be a nod to the still potentially rocky relationship between resale entities and brands, particularly as the secondary market continues to rise in value and as some brands test the waters with their own pre-owned efforts. Looking beyond the changes in terminology, these instances raise some interesting questions, including whether such strict stances by brands on the authentication front is what we want to happen from a policy perspective, especially in light of the sustainability/circularity benefits that come with a thriving secondary market.

Among these questions: Despite what some brands may suggest (and given the rise of AI-powered authentication services, such as those offered up by Entropy, which are used by luxury brands, themselves in some cases), are brands really the only ones that can authenticate products? Should brands be the only ones allowed to market themselves as capable of offering up 100% authentic goods? Also, what does it mean from a competition perspective for companies to take stands against others’ ability (or better yet, inability) to authenticate their wares?

It is worth noting that TRR alleged in response to Chanel’s lawsuit that the luxury giant has engaged in a variety of anticompetitive activities in violation of state and federal laws, including by misrepresenting that only Chanel can authenticate Chanel products, and filing suits against new resale market entrants “as a means to push [them] out of the market” because it views them as a threat to its ability to maintain a monopoly in the market for “top tier investment grade bags.” StockX has similarly argued in response to Nike’s suit that the case is an example of Nike engaging in “anticompetitive behavior [that] will stifle the secondary market, hurt consumers,” and that is “an affront to the entire resale market.”

And at the same time, how important is it to consumers that resale entities be able to claim that their offerings are “100% authentic” as opposed to “verified”? The shift in language for StockX did not exactly garner goodwill for the company, with social media users calling out the reseller for “scamming” consumers and stating that they will patronize other resale sites going forward. It is unclear whether such pushback was born from the altered language, itself, or consumer misunderstanding of what the actual impact of the language change really is (which is arguably not much). It is also not immediately obvious if these outraged consumers will actually swear off StockX.

Ultimately, these questions and the larger issues that they point to, including from a competition point of view, are not inconsequential, and in fact, they will likely continue to come up – and grow in importance – as the value of the resale market continues to climb.