Shein – the fast fashion retailer that surpassed Amazon as the most downloaded shopping app in the U.S. in May – is not only facing flak for allegedly infringing other companies’ trademarks, it is coming under fire for failing to make “public disclosures about working conditions along its supply chain that are required by law in the United Kingdom, and until recently, falsely stated on its website that conditions in the factories it uses were certified by international labor standards bodies,” according to Reuters, marking the latest issues with the stunning rise of the burgeoning Chinese fashion empire.

In a report on Friday, Reuters revealed that by failing to “provide a statement on a searchable link available on a prominent place on its home page, dated to a financial year and signed by a director, outlining the steps it is taking to prevent modern slavery in its supply chain,” Guangzhou, China-headquartered Shein is running afoul of the UK’s Modern Slavery Act 2015 (“MSA”), which requires that, among other things, qualifying companies prepare – and make publicly available – an annual statement of the steps taken to ensure slavery and human trafficking are absent from their operations and supply chains.

Specifically, the MSA requires qualifying companies to disclose their policies on slavery and human trafficking; details of the due diligence processes they undertake in relation to their business and supply chains; the effectiveness in ensuring that slavery and human trafficking is not occurring in their business or supply chains; and the training provided to staff. Alternatively, companies are required to declare if steps have not been taken.

Modern Slavery Reporting

While privately-held Shein does not publicly disclose its annual revenues, analysts have estimated that it generates sales of at least $5 billion per year, which would put the company in the crosshairs of the MSA, which applies to commercial organizations with an annual global turnover of at least £36 million ($50.05 million) that do business in the UK. The MSA also requires that foreign companies that do business in the UK, and foreign subsidiaries of UK companies that produce goods and services sold or used in the UK, comply with the law.

A spokesperson for Shein told Reuters that the company is in the process of finalizing statements required by UK law, stating, “We are developing comprehensive policies, which we will post on our website in the next couple of weeks.”

To date, the requirements of the MSA are not backed by “any meaningful sanctions,” per Eversheds Sutherland counsel Vadim Chaban, and instead, the UK government “takes the view that the companies that fail to take action will face commercial pressure to do so, as reputational damage and competitive disadvantage could be significant.” The government can, however, seek injunctive relief for any businesses that fail to meet their obligations under the MSA.

In light of increased attention to the risks of modern slavery among regulators, the lack of monetary penalties for companies that fail to comply with the MSA appears to be changing, as UK foreign secretary Dominic Raab confirmed early this year that the UK government, for one, intends to “introduce fines for businesses that do not comply with their transparency obligations.” According to a note from Pinsent Masons partner Sean Elson, “The UK government’s move to introduce new financial penalties for non-compliance with the requirements of the Modern Slavery Act is part of a package of measures it announced to address alleged human rights abuses in Xinjiang, China.” The impending changes are expected to go beyond reporting and impact “suppliers, where there is sufficient evidence of human rights violations in any of their supply chains.”

Outside of the UK, Reuters found that Shein also failed to abide by similar rules in Australia, which came into effect in 2018, and classify companies doing business in the country that have annual consolidated revenues of at least $100 million as “reporting entities,” and require them to file an annual statement with the Department of Home Affairs and Australian Border Force for publication that describes the risks of modern slavery in their own business and supply chains, and that clearly states what they are doing to help combat those risks. Much like with the UK’s MSA, the law in Australia also currently lacks financial penalties for noncompliance, although Mills Oakley attorneys Luke Geary and Georgia Davis state that “under a similar law, which is yet to commence, there may be fines of up to $1.1 million.”

The Australian modern slavery law does, however, enable the Minister of the Department of Home Affairs to request that “a reporting entity provide an explanation for its failure to comply, and/or require the entity to undertake specified remedial action, within a set time,” and if the entity fails to adequately company, “the Minister may publish the identity of the entity, as well as details of their failure to comply.”

Infringement Suits

The labor reports come as Shein has made a steady – and largely quiet – climb to the top of the fast fashion totem pole with its $11 dead-ringers for Cult Gaia’s hot-selling Serita dress, lookalike Marine Serre tops for $8, and its copycat versions of Gucci, Dior, and Bottega Veneta bags all for less than $30, all of which are aimed at millennial and Gen-Z consumers in the West.

The Financial Times reported in June that Dr Martens-owner Airwair had filed suit against Shein in a California federal court in late 2020, accusing Shein of manufacturing and marketing counterfeit footwear. At the same time, court dockets in the U.S. show that the burgeoning fast fashion brand and/or corporate entity Zoetop Business Co. have been named in a number of trademark and copyright infringement lawsuits in recent years by big names like Levi’s and Ugg-owner Deckers Outdoor Corp. and indie creatives like Katie Thierjung and Kjersti Faret, with most of those suits following the traditional course and quietly settling out of court.

Most recently, Shein was named in a trademark infringement and unfair competition lawsuit by Ralph Lauren, with the American fashion brand accusing Zoetop Business Co. of offering up apparel that includes trademarks that are “substantially indistinguishable and/or confusingly similar to one or more of Ralph Lauren’s marks,” namely, its famous polo player logo. According to Ralph Lauren’s March 2021 complaint, Zoetop’s infringement is “willful, deliberate, and intended to confuse the public and to injure Ralph Lauren” and in an “effort to exploit Ralph Lauren’s goodwill and the reputation of genuine Ralph Lauren products” for its own gain.

As for Shein’s notoriously low profile, which “is perhaps expected in times of geopolitical tensions and heightened regulatory scrutiny over China-related tech companies around the world,” as TechCrunch worded it this spring, that is slowly starting to fade thanks to a combination of infringement lawsuits, alleged labor reporting missteps, and of course, the sheer level fo demand for its wares among trend-happy consumers around the world.

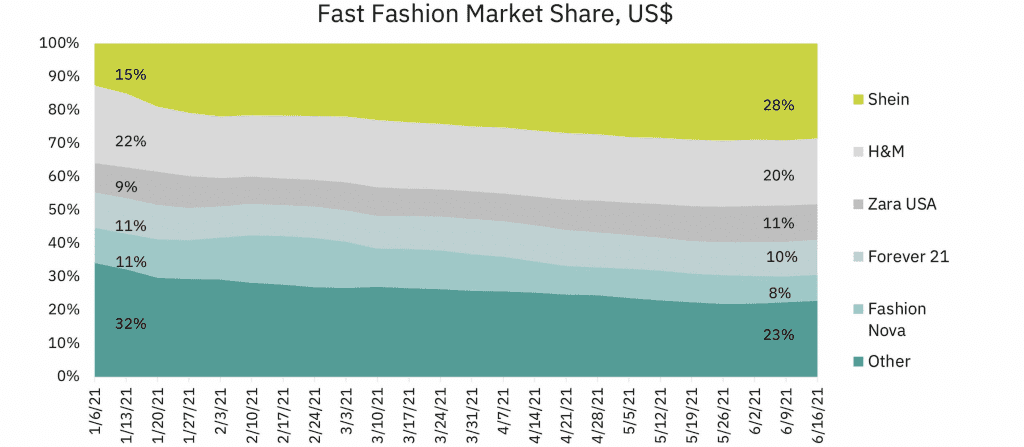

In terms of what that demand looks like, data consultancy Earnest Research puts it ahead of the likes of traditional fast fashion entities, such as H&M, Zara, Forever 21, ASOS, and Topshop, as well as even faster fashion names like Fashion Nova, Boohoo, Missguided, and PrettyLittleThing in terms of market share in the U.S., noting that the U.S. fast fashion market as a whole grew by 15 percent between January and mid-June 2021. According to New York-based Earnest’s data, Shein grew nearly 160 percent during that same period, which suggests that, among other things, “the brand’s mobile-first strategy has resonated with the post-Covid consumer.”