Copyright concerns and claims have been the focal point of much of the discussion around (and the cases filed over) generative AI – from whether artificial intelligence-generated artworks can be registered by the Copyright Office in the U.S. (we know that answer is no) to how we should treat the use of copyright-protected works in connection with the training of large language models. Issues on the latter front are playing out in real time in a growing number of lawsuits. Copyright-specific cases and concerns aside for a moment, it is worth noting that the role of right of publicity in the context of AI is becoming a bigger part of the conversation.

This week, Adobe’s EVP, General Counsel, and “Chief Trust Officer” Dana Rao published a blog post, in which he advocates for “an anti-impersonation right [to] protect artists from economic harm from the misuse of AI tools.” Rao calls this the “FAIR Act,” noting that while the White House has established voluntary AI commitments that have been signed onto by the likes of Google, Microsoft, Meta, Amazon, OpenAI, Adobe, etc., those commitments lack protections for creators’ styles. According to Rao, “In the generative AI world, it could only take a few words and the click of a button to produce something in a certain style. Someone could intentionally impersonate the style of an artist, and then use that AI-generated art to compete directly against the original artist in the marketplace, causing serious economic consequences.”

Continuing on, Rao states that Adobe’s proposed FAIR Act “specifically focus[es] on intentional impersonation for commercial gain.” (Emphasis courtesy of Rao). For example, he asserts, “If you explore someone’s style, build upon it in a unique way and find a commercial outlet for your own work in your name – that’s a different use case altogether and one we think should be able to continue in order to foster creativity and the progression of art.” On the other hand, “If you typed an artist’s name into a prompt and passed off the output for your own financial benefit, you’re hardly learning from or evolving their style.”

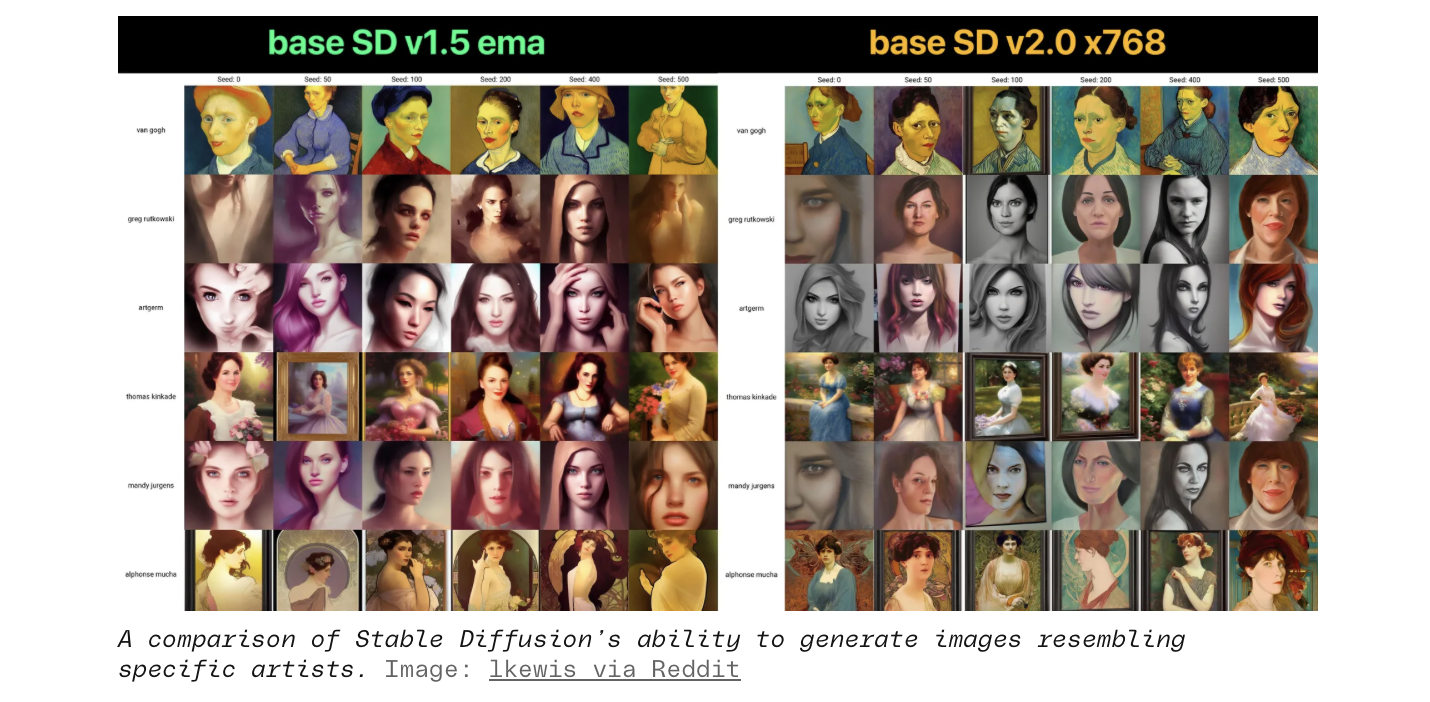

The latter is what the FAIR Act aims to address and it is essentially what the plaintiffs in a number of generative AI-focused cases are pushing back against. In Andersen v. Stability AI, for one, the artist plaintiffs claim that Stability AI is violating their common law rights of publicity by enabling users of text-to-image generator Stable Diffusion to create works “in the style” of a particular artist. The plaintiffs allege that Stability AI and co. has “used [their] names and advertised the AI’s ability to copy or generate work in the artistic style that [they] popularized in order to sell [the AI] products and services.”

Note: In Nov. 2022, when it released Stable Diffusion Version 2, Stability AI reportedly made it more difficult for users to mimic specific artists’ styles. That has not stopped plaintiffs like Andersen and co. from filing suit this year.

While plaintiffs are not without recourse for such alleged right of publicity violations thanks to state statutes, there is an emerging push for a federal cause of action, which is what Rao is getting at. “We believe one important way to [protect artists’ likenesses/styles] is for Congress to establish a new federal anti-impersonation right (FAIR) to protect artists from people misusing AI to intentionally impersonate their style for commercial gain,” he stated in the post.

> Not the first time he has pushed for a federal right of publicity statute, Rao raised the issue in his testimony before the Senate’s Intellectual Property Subcommittee this summer, stating that “a federal right of publicity could be created to help address concerns about AI being used without permission to copy likenesses for commercial benefit.” During that same hearing, which was part of a larger series that focuses on AI and IP, Rao was joined by artist/illustrator Karla Ortiz (who is one of the named plaintiffs in the Andersen v. Stability AI case), Universal Music Group’s General Counsel Jeffrey Harleston, and Emory Law professor Matthew Sag, who also spoke to the potential benefits of a federal right of publicity statute.

Sag, for instance, stated that there are “limits to what Congress can do to address” the issues posed by generative AI, asserting that he believes that “a national right of publicity law is needed to replace the current hodgepodge of state laws, and that we are overdue for a national data privacy law.” Going beyond the ability of AI generators to replicate an artist’s style, he noted that “if generative AI re-created someone’s distinctive appearance or voice, that person should have recourse under right of publicity,” and as such, he said that Congress should enact a national right of publicity law “to ensure nationwide and uniform protection of individuals’ inherently personal characteristics.”

> The Copyright Office also appears to be considering where right of publicity fits into the AI equation, raising the topic in a notice of inquiry last month. In one question that it posed to commenters, the Copyright Office appears to address calls for a federal cause of action, asking: “What legal rights, if any, currently apply to AI-generated material that features the name or likeness, including vocal likeness, of a particular person?”

> As for cases that specifically make right of publicity claims in connection with generative AI, there has been some movement in Young v. Cortext, with Judge Wesley Hsu of the U.S. District Court for the Central District of California recently denying NeoCortext’s motions to dismiss and strike, holding that Plaintiff Kyland Young has adequately pled that the AI-powered AI “face swap” app developer “‘knowingly’ used his identity when it compiled his images with his name in the Reface app and made the images available for users to manipulate,” and in doing so, met his burden to show “a probability of prevailing” on his right of publicity claim. On Sept. 8, NeoCortext lodged a notice of appeal to the Ninth Circuit following the court’s denial of its motion to strike.

> And from a practical POV, startups seem to be looking to address the potential right of publicity void – and the bigger conversation around the potential use of deepfakes in Hollywood, for example – if Metaphysic is any indication. This week, the London-based AI software company announced the launch of Metaphysic PRO, which it says can “help individuals and IP holders secure their face, voice and performance data used to train generative AI algorithms, while also providing solutions for the critically important issues of consent, compensation, and copyright.” Metaphysic’s proprietary platform “empowers individuals to securely create, store and protect their personal biometric data and manage how it is used by third parties and generative AI to build photorealistic performances, digital identities, and AI avatars.”

As of now, Metaphysic says that “notable users” of the Metaphysic PRO service, which “allows any performer to build a portfolio of their most valuable digital assets and AI training datasets over time,” include Anne Hathaway, Octavia Spencer, Tom Hanks, Rita Wilson, Paris Hilton, and Maria Sharapova.

At the same time, the WSJ reported in June that Hollywood talent agency CAA (soon to be acquired by Kering head François-Henri Pinault) had partnered up with Metaphysic, Soul Machines and other AI companies to “fully understand what’s happening and give our clients the best advice on how they can use [AI] to advance their careers and the various methods they can undertake to protect themselves,” citing CAA’s chief legal officer Hilary Krane. Aside from big-name actors and other celebs, WSJ stated this summer that from a fashion standpoint models “have also begun exploring ways to more actively manage their digital identities.” For instance, supermodel Eva Herzigova in April unveiled a virtual version of herself that can walk the runway in online fashion shows. “Ownership of the virtual version also rests with her and her agency, rather than with a brand or a photography studio.”