Chanel made headlines late last week when it revealed that it would raise its prices for the second time this year, citing “the consequence of recent significant exchange rate fluctuations between the euro and certain local currencies.” The French fashion house, which is known for its quilted flap bags and chain-handled “Boy” bags, is the latest in a handful of “high-end brands seek[ing] to protect margins from the fallout of the coronavirus pandemic,” per Reuters. A well-timed report from Bernstein finds that Chanel’s recent price push coincides with a larger trend over the past 40 years, which has seen the pricing of luxury bags – from the likes of Chanel’s flap bags to Hermès’ most well-known offerings – is increasing at 2x the level of the broader consumer price index.

What do such strong prices, which go beyond those associated with certain Chanel and Hermès bags, and include Rolex’s Daytona, Gucci horsebit loafers, and Louis Vuitton’s Neverfull, among other goods, mean for the industry and for investors eyeing the brands at play? The answer is not quite a straightforward as “merrily salut[ing] any luxury price hikes as great news.” According to Bernstein’s “Untapped Price Increase Reservoir” report, the rush to increase prices – which is a seemingly popular tactic at the moment among the likes of Chanel, Gucci, Louis Vuitton, Dior, and Prada, all of which have raised prices this year – is no simple matter.

While price increases might prove an immediately attractive signal for investors, experts fear that if prices continue to swell at this rate, luxury brands risk needing to implement “painful corrections,” and simultaneously eroding brand value in the process. Bernstein analyst Luca Solca points to Cartier as an example, noting that the Richemont-owned company is still paying for steep price-hikes in years past and has been forced to cut prices as quickly as they once raised them in some cases. (Cartier has gone from “surfing on gifting one day [to] cutting prices the next,” per Bernstein, which says that the brand “had one of the weakest price dynamics in recent years”). Nonetheless, some of the highest-earning brands today – Gucci, Louis Vuitton and Moncler, among them – are undeterred, parlaying their strong organic growth into increase their prices quickly.

In terms of the potential for price increases going forward, brands like Hermès, Dior and even Cartier (despite the aforementioned issues) lead the pack in terms of an “unrealized pricing upside,” which Bernstein measures by combining high consumer demand, vibrant organic growth, and limited price increases in the recent past. On the other hand, Bulgari, Prada and Longines show limited potential based on these same metrics.

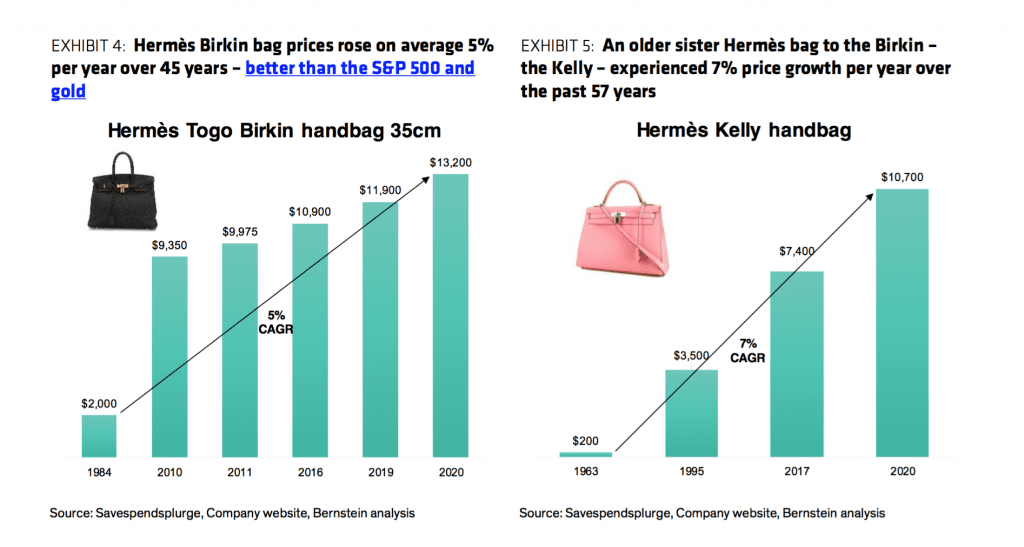

Meanwhile, elements such as bag resale value – which is “one way to tell the weak from the strong,” per Bernstein – and Google search strength, along with a positive five-year trend in organic growth, drive pricing power. Higher pricing power and lower realized price increases generates the desirable “untapped price increase reservoir” that investors seek. Hermès, for example, stands out here. The Birkin and Kelly-maker has exercised significant restraint and increased prices very conservatively, Bernstein asserts, especially given that it could have pushed forward with more aggressive raises. In the process, it has grown its reservoir and drawn the interest of consumers and investors, alike.

Looking specifically at China, the COVID-19 landscape has painted a pretty – if pragmatic – picture for both luxury fashion houses and the Chinese government on the price front. For years, the Chinese government has been pressuring luxury brands to reduce the price gap between China and Europe in an effort to corral Chinese spending on these goods on the Mainland. In 2019, 70 percent of Chinese spending on luxury items – a cool €70 billion of the total €100 billion spent on luxury goods by Chinese consumers – was done in the U.S. and Europe. So far this year, virtually 100 percent of Chinese luxury buys have been on the Mainland. The Chinese government, acting decisively to take advantage of this trend before post-COVID travel returns, has amended its duty free directives.

In terms of the price gap between Chinese and the U.S./European markets, that has somewhat reduced over the last four years, although the strongest performers of late – such as Louis Vuitton and Dior – maintain the largest price gap between China and France.

Research shows that luxury brands have split into two groups: those that continue to increase prices in China faster than Europe – namely, Louis Vuitton, Hermès, Burberry, and Saint Laurent – and those that have increased prices in Europe faster to bridge this divide – i.e., Gucci, Tiffany, Dior, Bulgari, and Prada. The Bernstein report indicates that the price gap is wider for soft luxury brands, as opposed to the narrower margins for hard luxury brands specializing in products like watches and fine jewelry.

Unsurprisingly given the appreciation of the U.S. dollar compared to the euro, the price gap between the U.S. and France has also decreased over the last five years. Luxury brands have reduced this price gap – via various price tag harmonization efforts – to average out at about 12 percent. Chloé, Celine and Chanel lead the industry, having reduced this price gap the most in the last four years. With such price corrections in mind, Chanel’s leather goods products are roughly 11 percent cheaper in the U.S. than in France, whereas Bernstein states that according to its price checks, “Burberry and Hermès products are virtually the same price in the two markets.”

The only departure from the 12 percent rule is Tiffany & Co., which sells at a 25 percent discount in the U.S. compared to their European prices for the same products.

For brands with a diminished price increase reservoir, hope is not lost. All one needs is to look to Prada, now regaining momentum after suffering from “over-ambitious” price increases five years ago. The Italian brand’s return to nylon bags – trendy again in their noughties nostalgia – at a lower entry price point has been a timely and effective method to drive sales. The lesson here: price inflation and brand desirability must dovetail for that price to take wing, and stay up.