Netflix made headlines in January when it formally turned Gwyneth Paltrow’s wildly polarizing Goop brand into a six-part docu-series called The Goop Lab. In each episode, the famed actress-turned-entrepreneur explores an area of the wellness industry, from psychedelics to sexual healing in true Goop fashion. In the weeks since its debut, the series has been slammed as “the most unsettling kind of sponcon” by the New Yorker, little more than “30-minute infomercials [for Goop]” by the WSJ, and responsible for pushing “junk wellness,” according to Vox. As for the scientific and medical community, experts have criticisms of their own, including concerns about Netflix “legitimizing pseudoscience and misinformation.”

The backlash against the barely 2-month old program is “unsurprising,” according to Stephanie Alice Baker and Chris Rojek, sociology professors at the City University of London, given that Paltrow’s brand – which started in 2008 as a newsletter – “has become synonymous with controversial products and treatments, such as jade eggs, Psychic Vampire Repellent and vaginal steaming.” Any looming concerns are accentuated, they say, by the fact that Goop is reportedly valued at over $250 million – with funding coming from big names in the venture capital community – and represents part of the burgeoning wellness industry, one that is worth a whopping $4.5 trillion as of 2017, according to the Global Wellness Institute. Sales in this segment are only expected to grow further.

More interesting than – or maybe: absolutely integral to – the rise of Paltrow’s flourishing brand and others just like it is “the difficulty in regulating [some of] its controversial content,” Baker and Rojek say, something that is representative of “larger difficulties in regulating online health and wellness influencers.”

Influencer marketing is a big business of its own; Business Insider projects that it could reach $15 billion in value by 2022. In this growing economy, influencers – i.e., individuals with the ability to influence the purchasing decisions of consumers largely via social media – have built big businesses by documenting their lives on social media and connecting with large audiences, “with some of the most successful health and wellness influencers achieving fame by curating an online persona on social media rather than by establishing professional expertise,” Baker and Rojek note.

Thanks to her own authenticity-centric approach to everyday health and wellness issues (and her cult following of die-hard Goopers), Paltrow has, over the course of her 12 years at Goop, become something of the ultimate wellness influencer.

According to Baker and Rojek, Paltrow’s alluring position in the wellness world “stems [in large part] from her apparent vulnerability, which she parlays into establishing credibility, [as well as] trust and intimacy with Goop’s audience.” The academic point to her Netflix series, for instance, saying that “Paltrow reflects on the trauma induced by the emergency caesarean she had following the birth of her daughter, how terrible she feels during a ‘cleanse’ and on her experiences ‘metabolizing’ pain. These communicative techniques set Paltrow apart from the jargon and professional distance required of medical professionals.”

And it works. Goop’s sales are “growing,” Paltrow told the New York Times last year.

In light of the enduring success of the Goop venture, which comes with equally enduring criticism that only seems to help propel Paltrow brand even more, one of the glaring questions is how do so many of the allegedly outrageous health and wellness claims that are made go without more pushback?

Of course there has been pushback: in 2018, for example, Goop paid $145,000 in connection with a settlement in a lawsuit filed against the company for making unsubstantiated claims about the benefits of its products. Thereafter, the company also found itself on the wrong side of an investigation initiated by a British non-profit, which pointed to 113 examples of advertising by Goop that allegedly run afoul of the law. Meanwhile, a U.S. ad watchdog has since made similar allegations.

But for a company that is so aggressively accused of pushing little more than “pseudo-science,” it seems like there should be more uproar on the legal front, no?

For Baker and Rojek, the answer is relatively simple: at the crux of the influencer-influenced relationship, which is a large part of the Goop-Goopee dynamic, is opinions. Look no further than the Goop Lab, which comes with explicit language asserting that it is “designed to entertain and inform” and not to offer medical advice. And no small amount of the alternative wellness content doled out by Goop is opinion-oriented and centers on the individuals’ own experiences.

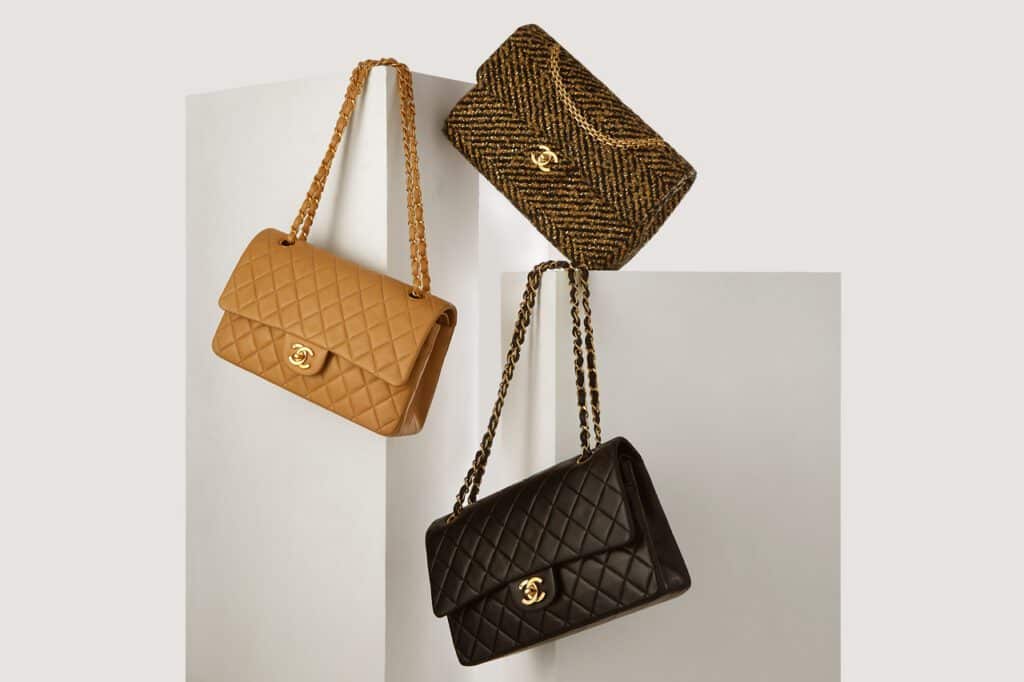

“Influencers claim to provide their own opinions,” the academics assert – on everything from handbags and hotels to face creams and food (depending on the influencer, of course) – “rather than facts.” After all, at the heart of the influencer hustle is these individuals’ ability to “monetize their personal lives and [their] opinions and thereby, profit from [commercial partnerships they can] link to their own daily lives and experiences.” It naturally follows that significant parts of these “self-documented journeys” are difficult to verify, and this lack-of-verification is – to a large extent – at the core of what drives the proliferation of non-traditional wellness gurus.

Add to that the fact that at least part of the appeal of the wellness movement can be understood by “the placebo effect,” in which a beneficial effect is produced simply as a result of an individual’s belief in the treatment or product, according Baker and Rojek. Goop almost certainly benefits from this, along with other similarly-situated companies, by “blurring the line between scientific research and folk knowledge” for most of its products. Instead of promising concrete, verifiable results, the company offers products designed to make consumers “feel good in the modern age world.”

Given that “feeling good in the modern age world” and similar claims are hardly quantifiable metrics, the products bearing this wishy-washy warranty of sorts are in the clear of having to substantiate results. It is only when objective claims are introduced into the equation that scientific proof for those claims becomes a factor.

Baker and Rojek provide a “case in point” by way of Goop’s body vibe wearable stickers, which it claims will “rebalance the energy frequency in our bodies.” While there was no issue with the stickers’ allege ability to “rebalance energy,” Goop came under fire for claiming that the stickers were “made with the same conductive carbon material NASA uses to line space suits so they can monitor an astronaut’s vitals during wear.” Turns out, a former NASA scientist spoke out, clarifying that it “does not [use] any conductive carbon material lining [its] spacesuits.”

Former chief scientist at NASA’s human research division Mark Shelhamer revealed that NASA spacesuits do not use any sort of carbon lining, and even if they did, it would be to add support and strength to the suit rather than to monitor vital signs, as Goop claims.

When it became obvious that Goop could not accurately make the claim that the stickers could be likened to NASA technology, the company altered its product language. What was kept as part of the marketing lingo: “the idea that people might feel better after wearing the stickers.” That language was able to stay because it could not readily be tested and substantiated (or unsubstantiated). That, Baker and Rojek say, is much “harder to verify.”

Ultimately, the academics assert that Goop and its Netflix series succeeds by “blurring the line between science and fantasy.” That enables it to make many marketing and promotional claims that sound appealing and without running afoul of the bounds of the law.