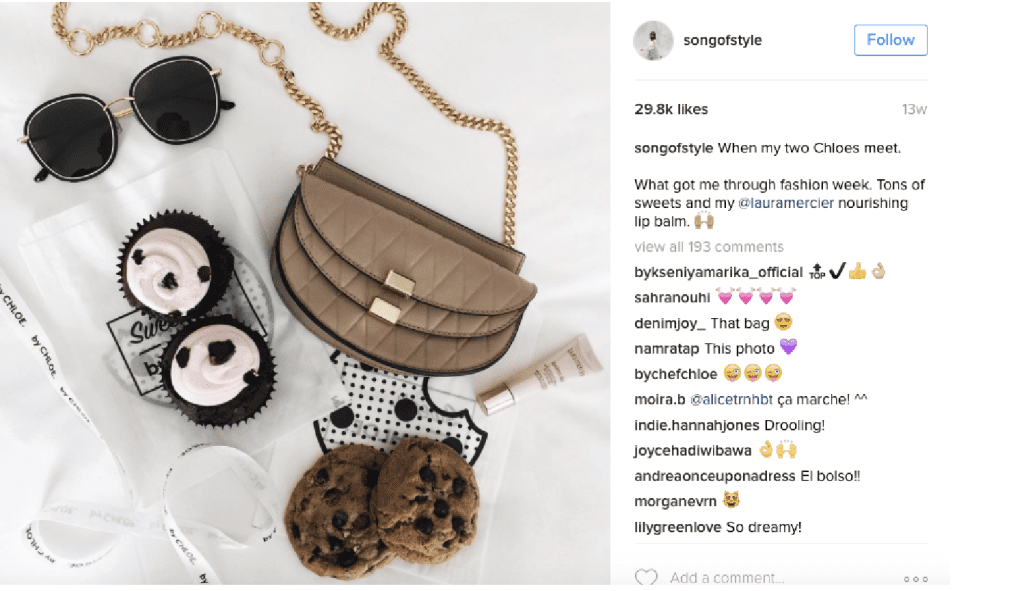

The news broke in May 2016 that Aimee Song landed a groundbreaking deal with beauty brand, Laura Mercier. The Los Angeles-based blogger, who is best known for her personal style site-turned-full blown brand, Song of Style, “just signed up to be Laura Mercier’s newest brand ambassador and its first digital influencer, inking a deal that’s believed to be one of the largest to date between a beauty brand and a blogger,” WWD noted. While both Song and Paris-based Mercier declined to comment on the financial figures associated with the partnership, it is reportedly worth upwards of $500,000. Of the deal, Song did offer: “It’s the biggest deal ever — and it’s not just [the money]. It’s the deepest relationship I’ve ever had with a brand.”

According to WWD, “The yearlong partnership has [Song] creating content for her blog at songofstyle.com, posting Instagram images and making appearances at fashion and beauty events on behalf of the brand. She’ll also create video content for lauramercier.com and incorporate it onto her own social channels to elicit maximum engagement from her 3.4 million Instagram followers.”

The problem: Less than a month after announcing the partnership by way of a post on her Instagram account and one on her blog – one that is heavily predicated upon Song’s social media prowess (and as WWD noted, specifically includes compensation for posting content on her Instagram account) – Song appears to already be running afoul of the Federal Trade Commission (“FTC”) Act, a federal law that governs the publication of commercial messages and prohibits the utilization of unfair or deceptive acts and practices in the market.

Posting endorsements – that have come about as a result of a connection between the endorser and the underlying brand – without proper disclosure are violations of the FTC Act. The same is true for the posting of sponsored content (regardless of the medium). And Song and Mercier are just two parties at the center of a massive scheme between the fashion industry’s most successful personal style bloggers and major fashion and cosmetics brands with the purpose of deceiving consumers for profit.

THE FEDERAL TRADE COMMISSION

The FTC is an independent government agency tasked with promoting consumer protection, and eliminating and preventing anticompetitive business practices. Established in 1914, the FTC garners its investigative and enforcement authority largely as a result of the FTC Act, under which it is empowered, among other things, to “prevent unfair methods of competition, and unfair or deceptive acts or practices in or affecting commerce.”

In line with its “unique dual mission to protect consumers and promote competition,” the FTC issues guidelines to aid the public in ensuring that advertisements are not misleading and thus, do not violate Section 5 of the FTC Act, which provides that “unfair or deceptive acts or practices in or affecting commerce are declared unlawful.”

The principles and policy considerations upon which the FTC Act and the corresponding FTC guidelines are predicated are simple. Consumers have the right to have access to “information they need to make informed [purchasing] choices,” and sellers “deserve the opportunity to compete in a marketplace free of deception and unfair practices.” Moreover, basic truth-in-advertising principles hold that it is deceptive to mislead consumers about the commercial nature of content, and advertisements/promotions are deceptive if they appear as though they are something other than ads.

With this in mind, the FTC Act states that an act or practice is deceptive if there is a material misrepresentation or omission of information that is likely to mislead consumers acting reasonably in the circumstances. Note: a misrepresentation is “material” if it is likely to affect consumers’ buying choices.

Hardly a novel concept, the FTC has long required advertisers and promoting parties – alike – to disclose material connections that consumers would not expect so that consumers can make purchasing decisions accordingly. So, when a celebrity or influencer is compensated (with money or free clothes or other perks) to endorse or promote a product outside of a traditional advertising medium (and thus, is not exclusively touting the product as a result of a genuine desire to do so), the parties must disclose this to consumers. The same holds true if the parties maintain a relationship of some sort, such as a brand ambassadorship. If the parties fail to disclose, the content will be deemed to be misleading and deceptive, and thus, in violation of the FTC Act.

As for why the inclusion of proper disclosures is crucial, Andrew B. Lustigman, who serves as chairman of the Advertising, marketing & promotions law practice at Olshan Frome Wolosky LLP, says: “They are important because people assume comments/postings on social media are authentic and unmotivated by any pecuniary benefit.” Regardless of disclosures, “the posted statements must still be authentic, but perhaps they will be weighed differently by consumers when they know compensation of some sort was involved.”

BLOGGERS & INFLUENCERS ARE SUBJECT TO THE FTC

The medium in which the promotion or endorsement is made does not matter, and so, the FTC’s standards apply to bloggers in the same manner as they apply to more traditional entities, such as magazine publishers and television broadcasters. Therefore, if a blogger is acting on behalf of an advertiser, “what she or he is saying is usually going to be commercial speech – and commercial speech violates the FTC Act if it’s deceptive,” per the FTC. This same concept also applies to social media, as well as native advertising. The FTC describes native advertising content as content that bears a similarity to the news, feature articles, product reviews, entertainment, and other material that surrounds it online, and this may include social media postings in the FTC’s opinion.

While the introduction of social media advertising and native content is relatively novel, the FTC has done an outstanding job of adapting with its development and widespread use, and has provided guidance as to how to abide by the FTC Act in such a medium. In particular, in March 2013, the FTC updated its “DotCom Disclosures” guidelines, thereby, laying out the ways in which advertisers and promoters/brand ambassadors/influencers can comply with the FTC Act. In December 2015, it similarly issued native advertising guidelines. Both sets of guidelines emphasize that consumer protection laws apply to both traditional media, such as television and print publications, in the very same way that they apply to social media and native content.

In particular, the FTC has held that in order to avoid violating the FTC Act by way of misleading or deceptive social media or native posts, promoting parties should use “#Ad”, “Ad:”, or “Sponsored” disclosures to indicate that a post or link within a post includes compensated content. As such, if a post – whether it be in a magazine, on a blog, or on social media – is the result of some form of compensation or partnership and is likely to appear to consumers as anything other than an ad, it requires a “clear and conspicuous disclosure” alerting consumers to the fact that it is an advertisement.

A common question, particularly amongst fashion industry insiders, is as follows: Isn’t it obvious that bloggers with millions of Instagram followers are being paid to promote products? The answer – straight from the FTC – is a resounding, NO! In the FTC’s own words: “Some bloggers who mention products in their posts have no connection to the marketers of those products – they don’t receive anything for their reviews or get a commission. They simply recommend those products to their readers because they believe in them. Moreover, the financial arrangements between some bloggers and advertisers may be apparent to industry insiders, but not to everyone else who reads a particular blog. Under the law, an act or practice is deceptive if it misleads ‘a significant minority’ of consumers. Even if some readers are aware of these deals, many readers aren’t. That’s why disclosure is important.”

WHO IS OUT OF LINE?

A significant number of major brands are consistently disregarding the FTC’s guidelines, and thus, the FTC Act, which, remember, is a federal law. As indicated recently by AdWeek, publishers, such as Cosmopolitan, are to blame, as well. “If the Federal Trade Commission decided to audit publishers’ native ads today, around 70 percent of websites wouldn’t be compliant with the FTC’s latest guidelines […] While most publishers are labeling branded content, they often violate FTC guidelines because the labels are too subtle or aren’t positioned in the correct place,” according to the April 2016 article.

The same can be said of bloggers, who are playing fast and loose with the FTC’s rules. Aimee Song certainly is. A brief review of her Instagram account reveals at least two Mercier-specific posts that are problematic, as they contain Laura Mercier products without one of the FTC’s recommended disclosures. Instead of including the approved disclosures, Song opts to use “#MercierPartner.” Disclosure in such a roundabout manner is significant, as it is prevalent amongst bloggers and brands, alike, and for a very specific reason.

An array of recent studies has shown that millennials do not respond most heavily when they know something is an ad. As a whole, they tend to prefer more authentic forms of marketing, hence, the rise of personal style blogs – which were long deemed to be more reliable and unhindered by the pressures of advertisers than traditional media outlets – in the first place.

In theory, millennial consumers are much more likely to engage with a brand or blogger/influencer and purchase something promoted by said blogger/influencer if they think the endorsement is authentic, and not because the individual was paid to endorse it. As such, it is a very common tactic for bloggers to either disclose in a way that is not obvious or fail to disclose material connections altogether for this exact purpose – both of which amount to willful violations of the FTC Act.

For industry insiders, who are well versed on Song’s deal with Mercier, #MercierPartner may be a potentially obvious attempt to disclose her connection with the brand. However, that is not sufficient to shield Song from potential FTC liability because the FTC does not gauge disclosure clarity by fashion industry expert standards. Instead, the FTC has held, “An act or practice is deceptive if it misleads ‘a significant minority’ of consumers.” Chances are, Song’s #Partner disclosure will still leave a significant minority of consumers unsure as to whether these Instagram posts are the result of a financial relationship between herself and Mercier, and as a result, such disclosures would likely fail to meet the FTC’s requirements.

Note: While Song did, in fact, dedicate a post on Instagram and on her website to the fact that she signed a deal with Mercier, the FTC would almost certainly find that this would not let her or Mercier off the hook for subsequent failures to disclose. Why? Well, because there is a very significant chance that “a significant minority” did not read that initial post or see that first Insta photo, and therefore, would not be privy to such partnership information. Also know, the FTC is a big proponent of repeating disclosures with every single post to ensure the utmost in clarity for consumers.

It is unfair to single out Song and Mercier, as the practice of failing to uphold the tenants of the FTC Act is extremely rampant among the fashion industry’s most successful bloggers and the brands with which they partner.

Take the Suarez sisters, Dylana and Natalie, for instance. The sisters, who are mid-tier bloggers (read: not nearly as famous at Song but not unknown names, either) were among the 50 bloggers, who were tapped (and subsequently called out by the FTC) for taking part in the problematic Lord & Taylor Design Lab campaign and not labeling the sponsored posts correctly. It seems that such failure to disclose is still part of their practice, as they recently partnered with TEVA and did not indicate that relationship on any of their combined twelve Instagram posts featuring the famed sandal brands’ shoes. That is one just example.

Also in terms of smaller-scale bloggers, Christina Caradona of Trop Rouge has also engaged in a number of similar campaigns, such as ones with Sperry, Marc Jacobs x Uber, and Target, without including the appropriate disclosures.

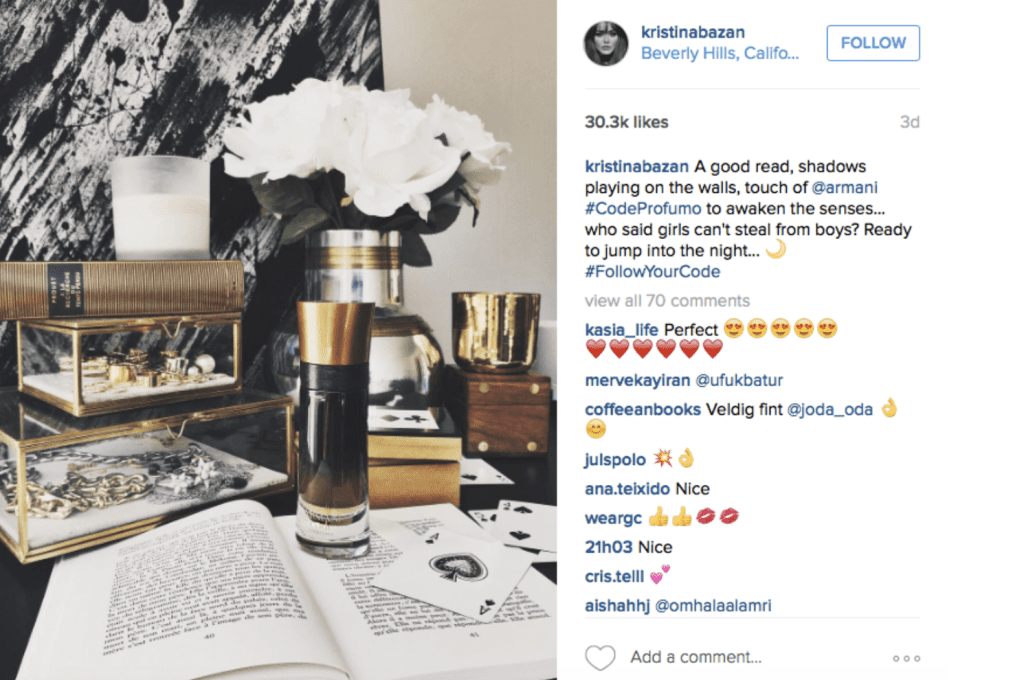

Now consider Song’s fellow LA-based mega-blogger, Kristina Bazan, who boasts a following of 2.3 million on Instagram. According to WWD, Bazan “reportedly signed an exclusive one-year contract with L’Oréal in October that’s worth at least $1 million. The 22-year-old blogger’s ambassadorship reaches beyond the digital space.” This is an extremely damning bit of information if we review Bazan’s Instagram, which consists of an array of potential violations, some (but not all) of which are directly tied to L’Oreal, and none of which are accompanied by disclosures.

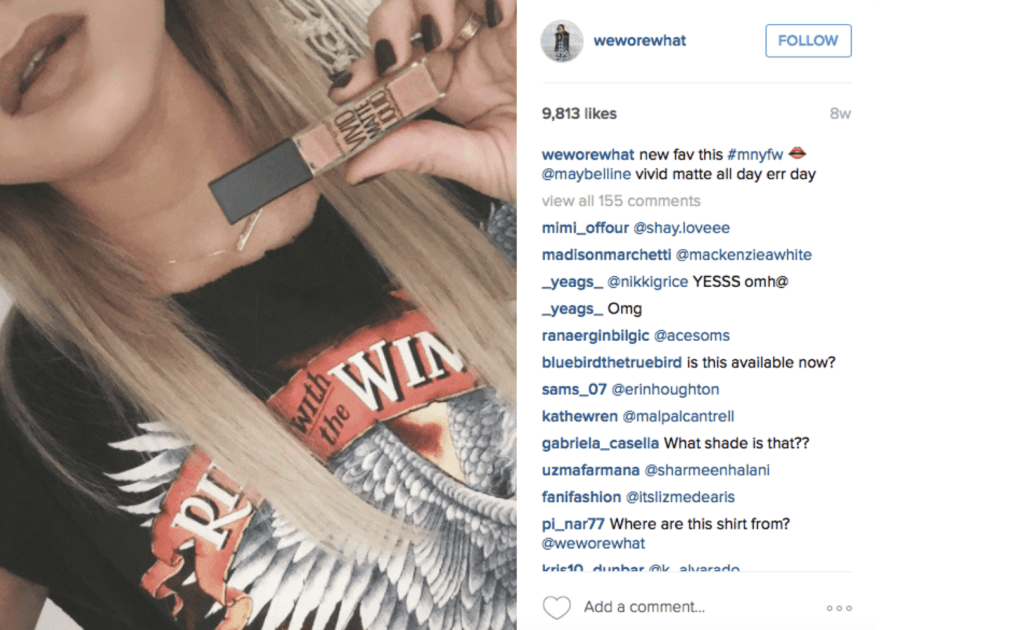

WWD has also revealed that “Danielle Bernstein of We Wore What had a contract with Maybelline during New York Fashion Week in February and Julie Sarinana [of popular blog, Sincerely Jules] worked with La Mer in a similar capacity earlier this year.” With this in mind, both Bernstein and Sarinana – with their respective 1.4 million and 3.4 million Instagram followers, are in violation of the FTC Act, as are Maybelline and La Mer. Bernstein posted a number of Maybelline-specific posts on her blog and Instagram during NYFW without disclosures.

Note: According to an article from the Telegraph this past May, Bernstein makes roughly $15,000 per Instagram post. Referring to an interview between Harper’s Bazaar and Bernstein, the Telegraph’s Bibby Sowray writes: “Since the interview [Bernstein] has hit 1 million followers, meaning she can now charge ‘a good amount more.’ She’s coy about exactly what means number-wise but we can assume it’s north of the latter figure.”

Similarly, Sarinana failed to disclose the aforementioned partnerships, as well, and as a result, her undisclosed Instagram posts that include La Mer products are likely problematic. Moreover, her blog post, entitled, “Oh, La Mer!,” which is categorized as a “Collaboration” is also questionable, as it does not include a disclosure in the article itself, and chances are, “Collaboration” would not meet the clarity requirement imposed by the FTC.

There is also Chriselle Lim of the Chriselle Factor to consider. She “worked with Dior surrounding the launch of Dior Prestige La Crème in November of 2015 and has also produced sponsored content around the brand’s Dior Addict lip colors. Like Song and Ferragni, Lim has worked with SK-II since last year, and in 2014 worked with Estée Lauder to create a series of videos,” per WWD. All of the aforementioned relationships, as well as her relationship with Ferragamo, went undisclosed by Lim on her Instagram account, as well as on her website. “#Chrisellefordior” will certainly not suffice, and chances are “#LaMerIcon” in connection with her work for skincare company, La Mer, will not cut it either.

Do not forget Leandra Medine, the blogger behind The Man Repeller. In the past month alone, she has featured posts on her site and her social media accounts in connection with deals with H&M, Mulberry, Seezona, and Levi’s. None of the aforementioned posts came with proper FTC disclosures. She has, however, included #MRPartner in some of the social media captions, which as we mentioned, is likely insufficient according to the FTC’s guidelines.

And last but certainly not least: What about Chiara Ferragni, the uber-successful blogger-turned-businesswoman behind the Blonde Salad? According to WWD’s article, Ferragni “has beauty partnerships that span YSL beauty, SK-II, Eyeko, Ormana, Chanel, Dior, Kenzo and Pantene. The latter, inked at the end of last year, is the biggest deal of the group and rumored to be in the mid-six figures.”

Maybe the most problematic figures in connection with the FTC guidelines, Ferragni has failed to disclose almost ALL of the aforementioned business connections – both on her Instagram (which boasts 6 million followers) and website. That is right. Not a single one of the Instagram posts has been labeled as an “ad” or as “sponsored,” and neither have the corresponding blog posts. For instance, consider the ten-plus undisclosed Instagram posts touting Ormana products and the various inclusions of Ormana products on her blog. The same goes for the SK-II, YSL Beauty, Eyeko, Chanel, Dior, Kenzo and Pantene placements.

We can add a number of other big-name brands and bloggers to this list – all of which are represented by established talent management agencies. In fact, just about every major personal style blogger currently has at least a headful of undisclosed posts on their Instagram feeds (save for maybe BryanBoy, who deserves commendation for routinely disclosing his sponsored posts and distinguishing gift-related posts).

The unabashed frequency with which the FTC Act and its guidelines are plainly overlooked and/or disregarded by professional bloggers and the companies with which they are associated is quite shocking, and the likelihood that consumers are being deprived of valuable information as a result is extremely high. This is particularly true given the origins of personal style blogs – as distinct from more traditional media sources – and the fact that they were long considered more independent and/or objective sources of information compared to their traditional counterparts. This has obviously changed quite a bit as advertisers identified the vast amount of advertising opportunities – both outright and native – that come in the form of personal style blogs.

To add to the already significant amount of confusion, consider that many personal style blogs do, in fact, still consist of non-sponsored posts, at least to some extent, which are thereby combined with sponsored posts. In the absence of proper disclaimers, consumers do not stand a chance in properly distinguishing between sponsored and non-sponsored posts, and neither do advertisers, who opt to follow the law and monitor such advertising. Frankly, such negligence – either willful or otherwise – is certainly resulting in the widespread deception of consumers and contributing to a marketplace that is founded upon unfair competition in violation of federal law.

LIABILITY FOR FTC VIOLATIONS

As for who will be held liable if the FTC were to take action, chances are it would be the advertisers. So, the Laura Merciers, the L’Oreals, the Le Mers, the Tevas would be held liable and not the bloggers, as the advertising brands are tasked with ensuring that their hired help is abiding by the law. While the FTC does, in fact, have the authority to take action against bloggers, it has thus far chosen to focus its energies entirely on the advertisers, which it deems to be more responsible for such potentially illegal behavior. This was recently demonstrated in connection with the Lord & Taylor Design Lab proceeding. Despite the fact that Lord & Taylor enlisted and compensated 50 top bloggers to post images on their individual Instagram accounts – all without disclosures – the FTC limited its action to that against Lord & Taylor.

A Lord & Taylor campaign post edited to include #ad (image: @natalieoffduty Instagram)

That proceeding was settled in March, and as a result, Lord & Taylor is barred from presenting advertising that it pays for as coming from an independent source, such as a magazine or the individual bloggers, for a period of 20 years (which may be even longer if Lord & Taylor does not monitor compliance and violates the order going forward). It also imposes comprehensive disclosure, monitoring and reporting obligations. Specifically, Lord & Taylor must provide each of its endorsers with a clear statement of his or her disclosure responsibilities and obtain from each endorser a signed statement acknowledging receipt. Lord & Taylor must establish and maintain a system to monitor and review its endorsers’ disclosures to ensure compliance with the FTC Endorsement Guides, and terminate any endorsers who fail to disclose their relationship with the retailer. The consent order also requires that Lord & Taylor maintain reports sufficient to show the results of its monitoring, which is a burdensome task when dealing with hundreds of influencers and possibly thousands of social media posts.

While the FTC has chosen to place all liability on the advertisers in the proceedings to date – the vast majority of which center on matters involving pharmaceutical products and financial dealings – there is a very real chance that given the evolution of deals in the fashion industry, such as Ms. Song’s, this may change. As indicated by the monetary sums at stake and the truly enormous followings that these influencers have, the stakes are very high; these are not small-time bloggers. No, these are individuals who make their livelihoods from blogging.

If the aforementioned instances of potential violations by Song, Bazan, Ferragni, Lim, the Suarez sister, and company are any indication, change is upon us. To date, the FTC has not been faced with such massive schemes by brands in connection with such truly substantial bloggers. The monetary compensation at issue – note all of the bloggers took in tens, if not hundreds, of thousands of dollars for their deals, according to reports – will likely call for greater action by the FTC.

Maybe more importantly, however, is the size of the social media followings at issue; these women maintain followings of millions of individuals on social media and beyond, and as a result, they wield significant power to influence, and thus, deceive consumers when they fail to disclose their relationships with brands. This is exactly the type of communication the FTC is tasked with addressing. Therefore, it would hardly come as a shock if the FTC were to take action against these professional bloggers in order to make an example for the industry at large.

Given the high stakes at hand, all signs point to indications of what is to come, namely, that the FTC will likely change its tune and begin treating bloggers as parties in such actions. Legal experts in the field certainly seem to think so. According to Lustigman, it is likely only a matter of time. “I would expect that the FTC will go after individuals. For example, in more traditional media, the FTC has gone after endorsers. So, I would expect so here,” he says.

With this in mind, be sure to disclose your posts, bloggers. Use the hashtag “Ad” or “Sponsored” in social media posts, and be sure to utilize easily identifiable (read: not hidden) disclosures in blog posts. As for the brands, you need to carefully monitor your influencers and ensure that they disclose sponsorships properly. If you’re found in violation of federal law, the FTC could disgorge you of all related profits.

* This is Part I of what will amount to a longer-running series examining the state of FTC disclosure failures by the fashion industry at large and presenting guidance on how to avoid similar pitfalls. Part II, a How-To Guide for Proper Disclosures, will be published shortly.