With big names like Gucci, Prada, Valentino, and Versace operating within its ranks, Italy’s fashion and textile industry is the second largest manufacturing sector in the country (after metallurgic). Employing some 600,000 people and representing at least 20 percent of national exports, the industry generates 95 billion euros ($98 billion) in annual revenues, according to Reuters, making it not only one of the largest segments of the Italian market (and that of the European Union), but also one that has benefitted from steady growth in recent years, growth that has since been hampered by the onset of COVID-19, which is precisely why the industry is being given specific attention in new economic legislation.

Following its initial enactment in May, Law Decree No. 34, or the “Rilancio Decree” – an Italian law that introduced a number of economic measures in response to the COVID-19 crisis – was revamped this month to include a number of amendments in furtherance of its larger goal to provide corporate and tax measures to support Italian companies in light of the sweeping manufacturing disruptions and greater market volatility cased by the COVID pandemic. Among the new additions to the law, which first went into effect on May 19, 2020 and pledged an additional €55 billion in stimulus measures to help “relaunch” the Italian economy, is a specific provision that aims to provide tax credits for entities in the “textile, fashion and accessories sectors” in connection with their “final stock inventories.”

According to Baker McKenzie’s Mariassunta Pica, Bianca Bagnoli, and Marzio Bucciol, the July 19, 2020 amendments include one that states that for the 2020 fiscal year, “Taxpayers carrying out business activities in the textile, fashion and accessories sectors may benefit from a new tax credit equal to 30 percent of the value of their unsold inventory at the year-end that exceeds the average of the inventories booked in the three previous fiscal years.”

The law requires that in order for a company to be eligible for such a tax credit, which will offset tax and social security liabilities pertaining to the fiscal year, “the inventories must be evaluated by using the same methodology and criteria both in the [2020] tax period and in the three previous tax periods.”

The new amendment – which comes on the heels of efforts by various major Italian apparel industry trade organizations and lobbying groups to push the country’s government to enable fashion and luxury brands to resume work on the basis of the “lasting damage” that could be caused to the county’s economy and the viability of its apparel sector as a result of a potential “economic epidemic” – appears to be a clear nod to the COVID-induced disruption to the state of the global apparel market. Between widespread interruptions to global supply chains, including those for various types of raw materials (from textiles to product packaging), and the ever-growing number of fashion industry order cancellations, Italian brands and manufacturers, alike, have been impacted significantly.

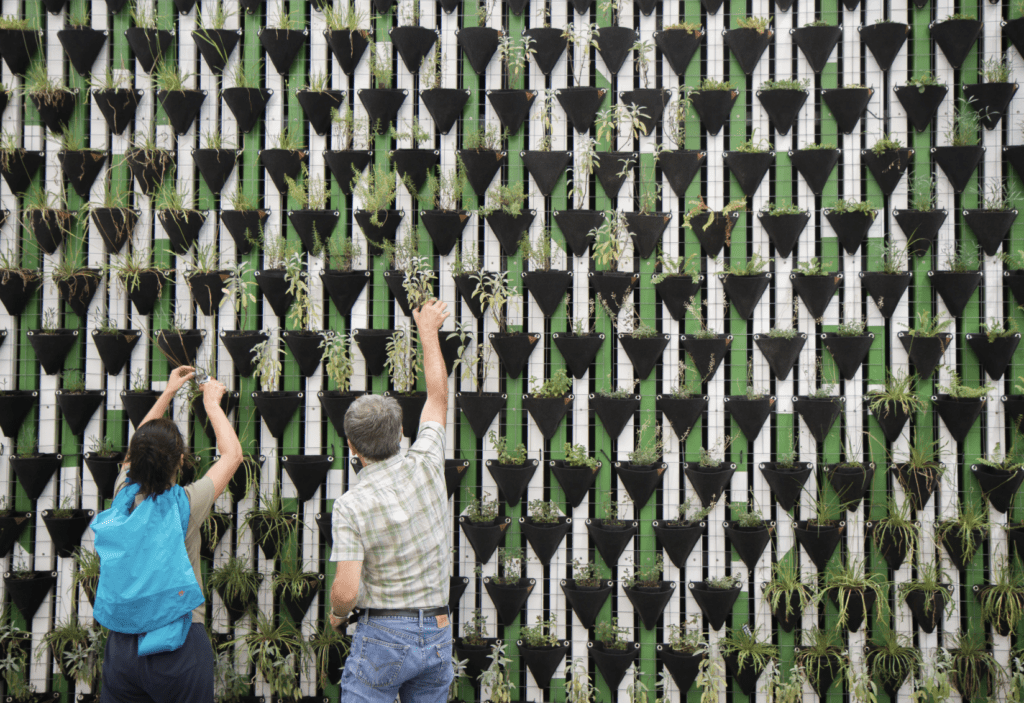

“The supply chain is a disaster,” David Shiffman, co-head of consumer and retail banking at investment bank PJ Solomon, told Bloomberg, and Italian entities are not immune. In addition to the risk that items go out of style, “there’s a limit to how much you can pack away for next year, because you’re packing away your cash,” he notes, referring to the practice that some brands are turning to in order to salvage some of the full-price sell-through potential for their unsold wares.

There is also a limit on how much any brand can rely on discounting in order to sell off unsold inventory. Jean-Marc Duplex the CEO of Gucci’s parent company Kering stated in a call with investors in April that Kering would enact “some discount activities” to improve sell- through for its inventory, in addition to extending the shelf-life for its house’s Spring/Summer 2020 garments and accessories. But in the luxury segment, discounting is not a magic bullet, as it must be balance with the aura of exclusivity, which is often achieved by brand-induced scarcity.

Ultimately, in addition to leaving companies with cancelled contracts and/or mountains of unsold wares as store-closure mandates and stay-at-home orders have affected consumers and business across the globe, COVID has stunted the quarterly and annual growth projections of companies like Italian mainstays like Prada, whose CEO Patrizio Bertelli revealed in March that COVID had already “interrupted our growth trajectory,” noting that the group “expects a negative impact on this year’s results,” a far-reaching reality for brands big and small, and a driving force behind the newly-enacted Italian law.