Deep Dives

Lawsuits over sustainability-focused claims continue to plague companies, as they look to cater to consumers by way of “green” products and corresponding marketing messaging. At least seventeen greenwashing class-action cases were filed or decided between June 2021 and June 2023, according to data from law firm Mintz, which notes that the number of “greenwashing” class action cases filed by private plaintiffs has significantly increased in recent years and “a large proportion” of these cases have survived motions to dismiss. Among the most common types of environmental, social, and governance (“ESG”) cases that were filed in 2022 and the first quarter of 2023, per Bloomberg, were those that take issue with “general environmental” marketing claims and claims that relate to product disposal.

A number of cases waged against apparel and footwear companies – typically in states with plaintiff-friendly consumer protection laws, such as New York, California, and Missouri, and by way of unfair competition, false advertising, misrepresentation, fraud, breach of warranty, and unjust enrichment causes of action – come to mind in terms of those that center on “general environmental” marketing claims. Among them are …

– Lee v. Canada Goose (filed Nov. 2020 in SDNY): Canada Goose was sued for allegedly making false representations that the fur on its jackets is ethically and humanely sourced when its suppliers use “cruel methods,” and as a result, it was running afoul of the DC Consumer Protection Procedures Act (“CPPA”), which prohibits false advertising, and violating various state consumer protection statutes. Canada Goose claimed in a motion to dismiss that its claims are substantiated by third-party standards, and George Lee argued in opposition that Canada Goose’s claims are still misleading, as those standards “authorize inhumane trapping practices that reasonable consumers would perceive as neglectful and unduly harmful.”

In June 2021, the court granted Canada Goose’s motion to dismiss in part, but Lee’s CPPA claims over Canada Goose’s representations about its “ethical and sustainable” fur sourcing survived dismissal. The case ultimately settled in April 2022.

– Dwyer v. Allbirds (filed Jun. 2021 in SDNY): Allbirds was named in a proposed class action for allegedly failing to live up to claims about the carbon footprint/environmental impact of its wool shoes, which it calculated using Higg’s life-cycle assessment tool. Patricia Dwyer accused the company of violating New York General Business Law (“NY GBL”) sections 349 and 350, the Magnuson Moss Warranty Act (for breach of express warranty), negligent misrepresentation, fraud, and unjust enrichment.

Granting Allbirds motion to dismiss in April 2022, the court found that Dwyer’s criticism was of the life-cycle assessment tool’s methodology, not with Allbirds’ statements about its products since Dwyer did not allege that Allbirds’ carbon footprint-specific calculations were wrong, or that it had “falsely described the way it undertakes those calculations.” The court also determined that Allbirds’ depictions of “happy” sheep were puffery, and thus, did not amount to any actionable representations.

– Lin v. Canada Goose (filed Sept. 2021 in SDNY): Jia Wang Lin accused Canada Goose of violating state consumer fraud and deceptive trade practices acts (including NY GBL s. 349), the Magnuson-Moss Warranty Act, negligent misrepresentation, breach of warranty, and unjust enrichment.Lin took issue with Canada Goose’s claims that its “Fur Transparency Standard” is its “commitment to support the ethical, responsible, and sustainable sourcing and use of real fur” and “certifies that we … only purchase fur from licensed … trappers strictly regulated by state, provincial and federal standards.”

In November 2022, the court dismissed the complaint in its entirety, tossing out Lin’s GBL claims, for instance, because Canada Goose’s “statements describing Canadian Hutterite down as ‘among the highest quality Canadian down available’ amount to nonactionable puffery,” and thus, would not “materially mislead a reasonable consumer.”

– Commodore v. H&M (filed Jul. 2022 in SDNY): Chelsea Commodore accused H&M of deceptive acts or practices, false advertising in violation of NY GBL, and breach of express warranty for using Higg scorecards to justify charging premium prices for its “sustainably-made” clothing products that are “no more sustainable than items in [H&M’s] main collection.” H&M filed a motion to dismiss in February 2023, arguing that the “foundation of this entire case rests on” the Commodore’s “strategic omission of key wording in H&M’s advertising.” Specifically, H&M argues that “[b]y removing the word ‘more’ from [its] statement ‘at least 50% more sustainable materials,’” Commodore “alters its comparative statements and leverages a repackaged version as a basis to claim widespread deception.”

– Lizama v. H&M (filed Nov. 2022 in E.D. Mo.): Plaintiffs filed a proposed class action against H&M for allegedly making “false and misleading” representations about its Conscious collection, and thereby, engaging in false advertising, deceptive acts and practices, and unjust enrichment, and running afoul of Missouri’s Merchandising Practices Act (“MMPA”). In a motion to dismiss in December 2022, H&M argued that by making claims about how its Conscious collection wares are “more sustainable” than its regular clothing, it is merely using comparative language, which would not mislead consumers into believing that its offerings are inherently “sustainable.”

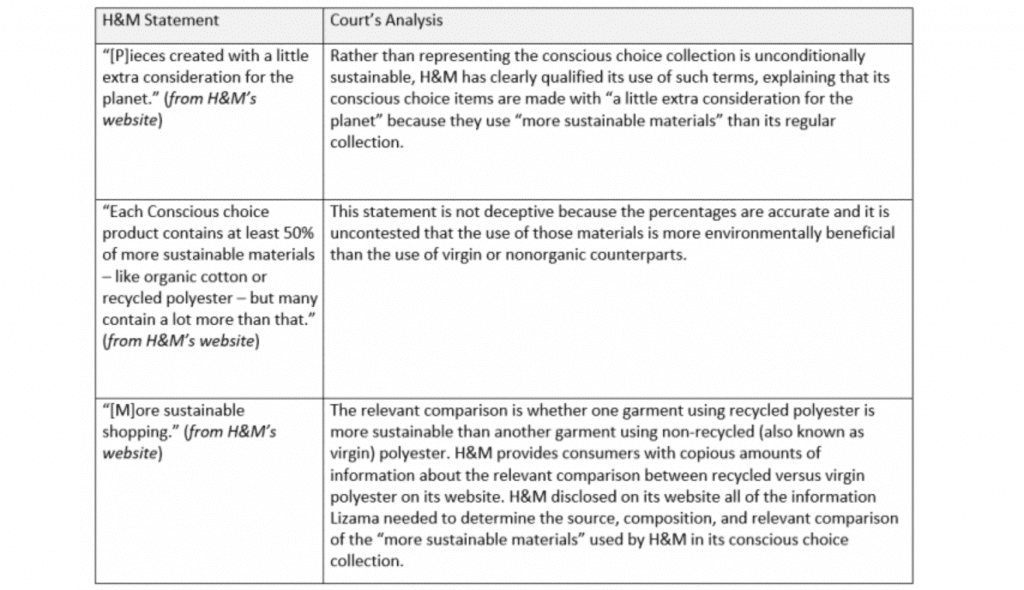

The court granted H&M’s motion to dismiss in May 2023 on the basis that the “only reasonable reading” of its ads is that the Conscious collection “uses materials that are more sustainable than its regular materials.” The court also noted that H&M “actually tells its consumers … that ‘fashion has a huge impact on the environment’ and that ‘the only trends worth following [are] recycling and repairing’ clothes.” Given the language on H&M’s website, the court said that “a reasonable consumer would not be misled into thinking that purchasing any new article of clothing (even from the Conscious line) was ‘environmentally friendly.’”

In short: The court ultimately found H&M’s statements were appropriately qualified and substantiated. Lewis Rice’s Emily Bardon and Lauren Rouse Carey put together the following snapshot of the court’s analysis of some of H&M’s allegedly problematic claims …

– Ellis v. Nike (filed May 2023 in E.D. Mo.): Maria Ellis filed suit against Nike in May, alleging that it is using marketing materials that are “replete with statements that [its] products are ‘sustainable,’ made with ‘sustainable materials,’ ‘eco-friendly,’ and environmentally friendly.” Contrary to Nike’s many “green” representations, Ellis alleges that the company’s products “plainly do notlead to ‘Sustainability,’ are not ‘made with recycled fibers’ which ‘reduce waste and our carbon footprint,’ do not support a ‘Move To Zero carbon and zero waste,’ and are not made with ‘sustainable’ and environmentally friendly materials.” Ellis primarily accuses Nike of violating the MMPA.

Nike has since filed a motion to dismiss, largely relying on the outcome in Lizama v. H&M, namely, the court’s finding that “disclosure of information regarding the representations at issue – through qualifying statements or additional context – can prevent a reasonable consumer from being misled.”

Reflecting specifically on ESG marketing cases, including some the matters above, Mintz notes that three key takeaways include: (1) Courts have generally denied motions to dismiss in cases where the defendant company made broad sustainability claims on product labels; (2) Courts have not considered third-party verification as definitive proof of sustainability claims; and (3) Courts have denied motions to dismiss in cases where the defendant company made demonstrably inaccurate statements that misrepresented a product’s recyclability, environmental impact, or sustainability. Still yet, the firm notes that “courts have generally dismissed challenges to representations based on publicly available methodology, corporate ‘aspirational statements,’” as seen in this case against Coca-Cola, for example, and “humorous statements or puffery.”

As for the second category of common cases, i.e., those that stem from companies’ claims about the disposability/recyclability of their products and/or product packaging, a currently-pending case waged against Coca-Cola Company and a number of other defendants (collectively, “Coca-Cola”) sheds light here. In that case, the plaintiffs – which include a trio of consumer plaintiffs and the Sierra Club – are taking issue with Coca-Cola’s claims that its bottles are “100% recyclable.” They argue that consumers are likely to understand the claim to mean that “the bottles will always be recycled or [are] ‘part of a circular plastics economy in which all bottles are recycled into new bottles to be used again.’”

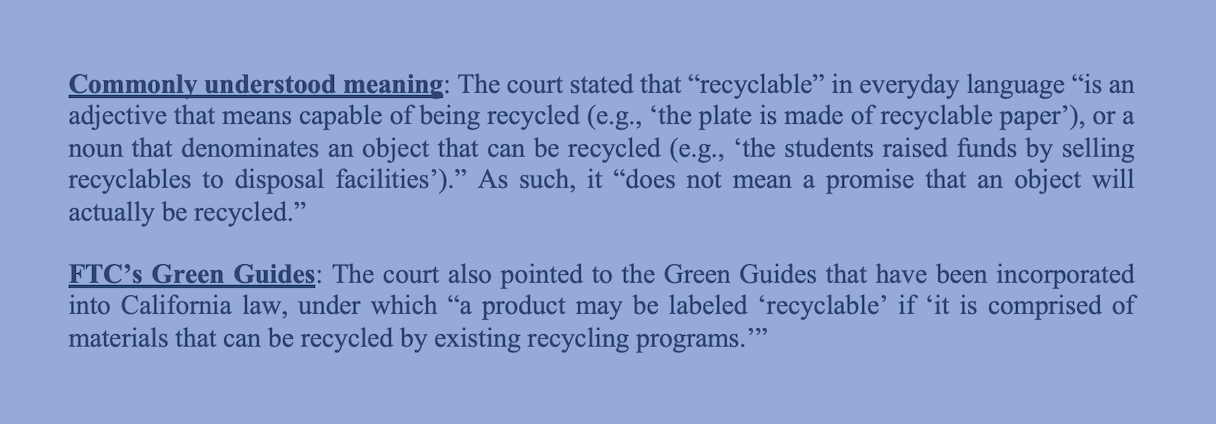

Some Background: The plaintiffs filed suit in a California federal court in June 2021, accusing Coca-Cola of false advertising; negligent misrepresentation; unfair, unlawful, and deceptive trade practices; violating the Consumers Legal Remedies Act; and interestingly, “greenwashing” under the Environmental Marketing Claims Act (Cal. Bus. & Prof. Code § 17580, et seq.). The district court granted Coca-Cola’s motion to dismiss in November 2022 (with leave to amend) on the basis that the plaintiffs had not plausibly alleged that Coca-Cola’s representations deviated from either the “commonly understood meaning of recyclable” or the definition in the Federal Trade Commission (“FTC”) Green Guides.

The plaintiffs filed an amended complaint – only to be shut down again last month. In his July 27 decision, N.D. Cal. Judge James Donato stated that the plaintiffs have standing to seek injunctive relief, as they plausibly alleged that they “would purchase the defendants’ bottled products in the future if the ‘100% recyclable’ representation were accurate and trustworthy because they believe that recyclable products are better for the environment.” However, the first amended complaint again did not “plausibly allege that the defendants’ recycling allegations are actionable,” according to the court. Specifically, the plaintiffs fell short in pleading facts to support their claim that recycling facilities that accept the bottle caps and labels are not available to a “substantial majority” (defined by the FTC as 60%) of the consumers or communities where the item is sold, which the plaintiffs “acknowledge is the pertinent question under the Green Guides.”

The plaintiffs have since filed a second amended complaint, arguing, among other things, that the defendants “do not fall within the Green Guides safe harbor. Instead of calling their products ‘Recyclable,’ they label them ‘100% Recyclable” (emphasis added). The addition of the ‘100%’ language suggests to consumers that the products exceed the ordinary standard of ‘Recyclability.’”

THE BIGGER PICTURE: The case at hand and others like it are particularly relevant in light of the number of sustainability marketing suits that are plaguing a growing number of fashion and retail companies, many of which are working to incorporate climate-centric messaging – including recycling-specific claims – into their offerings and related marketing campaigns. The issues on this front are compounded by the fact that there is an overarching lack of guidance from regulators (the FTC is in the process of updating its Green Guides) and there are mixed decisions from courts when it comes to the workings of sustainability claims (think: those that claim products/packaging are “green,” “recyclable,” “sustainable,” etc.) and relevant validation/substantiation.