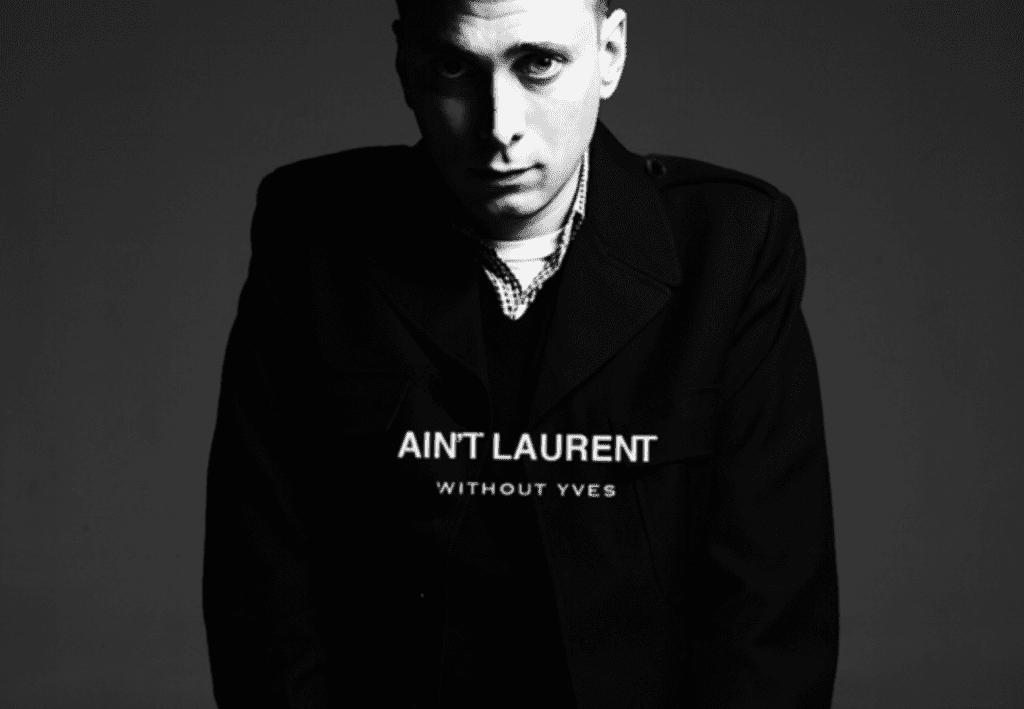

With the resurgence of so-called “parodies” – whether it be Vetememes raincoats or the more recent Henry Holland designer tees and Wood Wood x Champion windbreaker jackets – and recent attention to the matter from the European Union (“EU”), here is a look at the ongoing “parody” phenomenon that seems to come and go every few years in fashion, with the strongest wave in recent years coinciding with the popularity of Brian Lichtenberg’s “Homies” tees and the “Ain’t Laurent Without Yves” wares.

Many designers, retailers, journalists, bloggers, etc. have taken to grouping together all of the recent (and semi-recent) garments and accessories that make use of another brand’s name and/or logo, absent some (often minor) changes, and labeling them as “parodies.”

As we have told you in the past, such automatic characterization of these designs as parodies is very likely doing the designers a big favor – and the original trademark holders an equally large disservice. Instead of labeling these creations as illegal (think: trademark infringement or trademark dilution), they are being labeled as parodies, and thus, we are assuming they are protected under the doctrine of Fair Use. So, here is a quick review of some of the relevant statutes and case law in the U.S. and the European Union

U.S. LAW GOVERNING PARODIES

Starting with the basics: The Lanham Act. It is the primary law that governs the protection of trademarks in the U.S., and it establishes the right of trademark owners to attain a federal registration of their marks. Registration grants the trademark owner various rights, including the right to prevent others from using and registering marks that are confusingly similar to existing marks. The use of another’s mark (or one that is confusingly similar to it) amounts to trademark infringement, the test for which is essentially whether the secondary mark “is likely to cause confusion, or to cause mistake, or to deceive” consumers in connection with the original trademark owner.

The underlying theory for trademark law is consumer protection of sorts. Trademarks serve as an indicator of the source of the goods and services at issue, which necessarily entails a certain goodwill associated with each individual brand. By using a mark that is identical or similar to another brand’s trademark, you are likely to cause confusion, which is exactly what trademark law wants to avoid.

This is where parodies come in. The Lanham Act contains a statutory fair use provision, under which the use of another’s trademark may be considered non-infringing. These are: (1) nominative fair use; (2) comparative advertising as fair use; and (3) parody as fair use.

As such, parody is a defense to trademark infringement. The defense is that there is no likelihood of confusion because the parody will not be taken seriously. While it must initially bring to mind the original, it must be clever enough to be clear that it is not the original nor connected with the original, but is a parody, a humorous take-off on the original.

According to the case law, an effective parody should eliminate the “likelihood of confusion” implicit in a trademark infringement claim, as the parody should contain enough variations from the original trademark to clearly indicate that it is not related to the source of the original mark. In ruling against the creators of attempted trademark parodies, courts seem to generally rule in one of three ways: 1) that the use at issue does not amount to parody at all; 2) that a parody has been achieved but that parody is not strong enough to overcome the likelihood of confusion with the original mark; or 3) that a parody has been achieved but that parody is, nonetheless, diluting the underlying trademark.

The first ruling pattern concerns those that held that the alleged “parody” is not actually a parody at all. Courts generally define a parody as a work that imitates or mimics another work for comic effect or commentary. These courts have held that a work is not a parody if it simply exploits the popularity of the underlying trademark as a means of attracting more customers, or if there was an apparent likelihood of confusion between the two works.

Second: the alleged “parody” amounts to a parody, but that parody is not strong enough to dispel the likelihood of confusion among consumers. For instance, in 1977, the court held that “Gucchi Goo” diaper bags were too similar to Gucci handbags for the parody usage to be protected.

Lastly, the instance in which the court finds that the alleged parody is, in fact, a parody and there is no likelihood of confusion, but that the parody dilutes the original trademark owner’s mark. Dilution is covered by the Trademark Anti-Dilution Act of 1996, which grants injunctive relief to trademark owners to prevent their marks from dilution (aka – “the lessening of the capacity of a famous mark to identify and distinguish goods or services, regardless of the presence or absence of (1) competition … or (2) likelihood of confusion”).

And, of course, there are the times that courts rule in favor of the creator of the parody. In each of these cases, the court found that the defendants created strong parodies, and thus, decreased the likelihood of confusion to a sufficient degree that the court did not consider such instances trademark infringement. One example: Louis Vuitton and Haute Diggity Dog.

In 2007, the Fourth Circuit found Haute Diggity Dog’s use of CHEWY VUITON was a parody. The CHEWY VUITON toy was found to be similar in its name, monogram, design and coloring, which clearly indicated to the Court that the toy was an imitation. The Court also noted that all of the design and name elements were different. (e.g., Chewy/Louis, Vuiton/Vuitton). Each of the design elements Haute Diggity Dog selected to create the parody was close, but not identical to the design elements of the Louis Vuitton handbags. The Court found that Haute Diggity Dog did not infringe upon Louis Vuitton’s trademark.

More recently, the design house lost its case against a Los Angeles-based company, My Other Bag, which was offering “parody” canvas bags bearing its trademarks – with the Southern District of New York court holding that My Other Bag’s bags are, in fact, parodying Louis Vuitton, thereby shielding it from trademark infringement claims.

It is worth noting that in some cases, we have seen courts rule in favor of the parody uses, despite an existence of a likelihood of confusion. Courts have done so on First Amendment grounds, thereby signaling the importance of both parody and satire, for social commentary and commercial purposes. In fact, recent courts have been quite a bit more understanding of parodies of especially famous trademarks, in comparison to rulings in the past – the many parody cases that Louis Vuitton has lost in the past several years are prime examples.

However, each case is different and depends on the facts at issue, and so, whether the many, many “parodies” we see on the market at the moment are actually parodies is a difficult question. Thus, it is not safe to just assume they are, as the blogosphere tends to do.

EU LAW GOVERNING PARODIES

Since 2001, the EU has had parody legislation in effect in connection with copyright law. The Directive 2001/29/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 22 May 2001 – in Art. 5, §3, k – provides that member states may allow exceptions or limitations to the exclusive rights of a copyright holder “for the purpose of caricature, parody or pastiche.”

As recently noted by DLA Piper LLP’s Sara Balice and Elena Varese, in Johan Deckmyn and Vrijheidsfonds VZW v Helena Vandersteen and Others, a 2014 copyright case, “the Court of Justice of the European Union observed that there is no definition in the EU Law of the meaning and scope of a parody. Thus, such meaning should be determined based on everyday language. In light of this, the essential characteristics of a parody were found in ‘first, to evoke an existing work while being noticeably different from it, and, secondly, to constitute an expression of humour or mockery.’”

They continue: “the CJEU stated that, when determining the applicability of the parody-exception, it is for the member states’ courts to strike a ‘fair balance’ between the right holders’ interests and the rights of those who seek to make use of copyrighted works, by taking into account all the circumstances of the case, including for instance, the fact that the parody conveys a discriminatory message, which has the effect of associating the protected work with such a message.”

In terms of trademark law, while the EU has been slower to adopt parody-specific trademark legislation, Regulation (EU) No. 2015/2424 of the European Parliament and of the Council of December 16, 2015, now provides in its Recital 21 that “use of a trademark by third parties for the purpose of artistic expression should be considered as being fair as long as it is at the same time in accordance with honest practices in industrial and commercial matters. Furthermore, this Regulation should be applied in a way that ensures full respect for fundamental rights and freedoms and in particular the freedom of expression.”

We have yet to see a case where this legislation has played a central role, making it difficult to determine how a court would treat it. With this in mind, it is safe to assume that brands should tread carefully when utilizing another’s mark in a way you think is parodic.