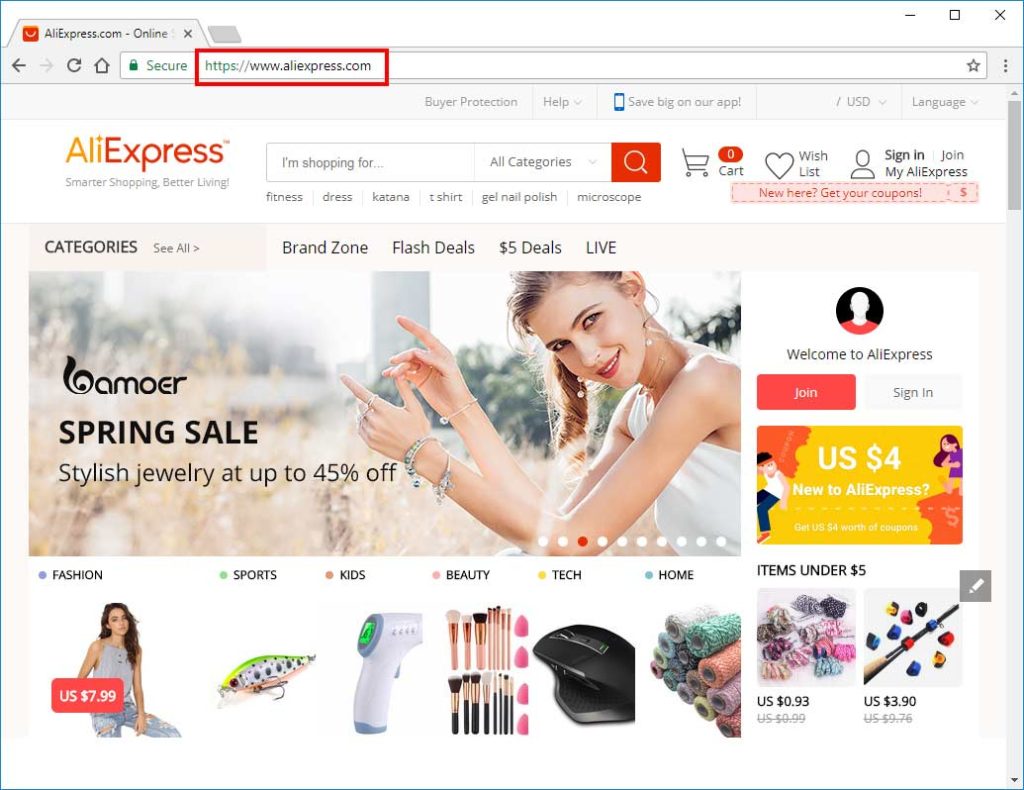

Amazon platforms were not among the names on the latest version of the U.S. Trade Representative (“USTR”)’s annual Review of Notorious Markets for Counterfeiting and Piracy. Released on Thursday, and based on nominations that it receives, as well as other input, such as from U.S. embassies, the Notorious Markets list highlights online and physical markets that “reportedly engage in or facilitate substantial trademark counterfeiting or copyright piracy,” and this year, identifies 42 online markets and 35 physical markets that are reported to engage in counterfeiting or piracy, including Alibaba-owned AliExpress and Tencent’s WeChat e-commerce ecosystem, two significant China-based online markets that “facilitate substantial trademark counterfeiting.”

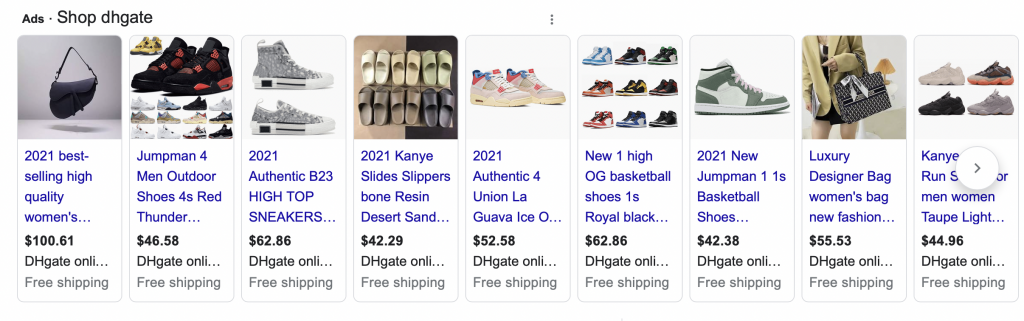

Among the other China-based entities on the 2021 “Notorious Markets” list, an official U.S. government intellectual property “black list,” are search-engine provider Baidu Wangpan, marketplace DHgate, social shopping site Pinduoduo, and Alibaba-owned Taobao, which appear on the list for another year in a row, along with nine physical markets located within China that the USTR asserts “are known for the manufacture, distribution, and sale of counterfeit goods.”

AliExpress, DHGate, PinDuoDuo & WeChat

Addressing the inclusion of AliExpress for the first time, the USTR stated in its report that despite falling under the Alibaba umbrella, which is “known for having some of the best anti- counterfeiting processes and systems in the e-commerce industry,” and boasting “much-improved communication with right holders, on their IP protection and enforcement issues,” rights holders have cited “a significant increase in counterfeit goods being offered for sale on AliExpress, including goods that are blatantly advertised as counterfeit and goods that are falsely advertised as genuine.” In addition to reports of “a vast increase in the number of sellers offering counterfeit goods” via AliExpress, the USTR asserts that “another key concern is that known sellers of counterfeit goods on AliExpress remain prevalent, purportedly due in part to the lenient seller penalty system and a removal process that does not deter sellers from continuing to offer counterfeit goods.”

Turning its attention to DHgate, the USTR states that the business-to-business cross-border e-commerce platform is reported to be “the most popular online market for purchasing bulk counterfeit goods that are then resold on other markets, including the online and physical markets listed in this year’s Notorious Markets list.” While DHgate pointed to “continued improvements to its seller vetting system,” the USTR, nonetheless, noted that “right holders again identified [its] inadequate seller vetting, ineffective proactive anti-counterfeit processes, and lack of transparency,” which the USTR puts forth as “likely reasons why the volume of counterfeit goods on the platform remains unacceptably high.”

As for PinDuoDuo, the USTR revealed that “despite significant improvements to its anti-counterfeiting tools, processes, and procedures in the past few years, the large volumes of counterfeit goods that stubbornly remain on the platform evinces the need to improve the effectiveness of the tools or close the gaps in their implementation.” Based on feedback from rights holders, the USTR states that Pinduoduo “appears to be moving in the wrong direction, with delays in takedowns, lack of transparency with takedown procedures, more burdensome and expensive processes, less effective seller vetting, and reduced cooperation with brands participating in the Brand Care program.”

And in a lengthy entry dedicated to WeChat, the USTR characterizes the Tencent-operated platform, which has 1.2 billion active users around the world in 2021, as “one of the largest platforms for counterfeit goods in China.” Of primary concern for the USTR when it comes to WeChat is the company’s e-commerce ecosystem, which “seamlessly functions within the overall WeChat platform and facilitates the distribution and sale of counterfeit products.” For example, the USTR states that sellers of counterfeit goods are allegedly “directing potential buyers to their counterfeit product offerings by advertising on WeChat [and] other communication portals.”

Amazon is Off

Maybe even more striking than the names that appear on this year’s list are ones that were not included. On the heels of a handful of the Amazon sites being included on the 2019 and 2020 versions of the Notorious Markets list, the Jeff Bezos-founded company has been wiped from this year’s list. (It is worth noting both that the USTR list is not an exhaustive measure of all markets that reportedly “deal in or facilitate commercial-scale copyright piracy or trademark counterfeiting,” just as it “does not reflect findings of legal violations or the U.S. government’s analysis of the general intellectual property protection and enforcement climate in the country concerned.”)

After reportedly skirting placement on the USTR’s Review of Notorious Markets in 2018, Amazon made headlines when a handful of its international e-commerce arms were officially cited in the 2019 list. In connection with its inclusion of Amazon’s Canadian, United Kingdom, German, French, and Indian platforms, the USTR asserted that “submissions by right holders expressed concerns regarding the challenges related to [Amazon] combating counterfeits with respect to e-commerce platforms around the world.”

No small matter, the inclusion of Amazon sites on the U.S. government’s list in 2019 and again in 2020 was characterized as a “watershed event,” due to the company’s American heritage, and it marking the first time that an American company was targeted on the annual list since it was first published by the USTR in 2006. In adding Amazon’s sites to the list in 2020, the USTR cited rights holders’ challenges with “high levels of counterfeit goods,” and concern that “Amazon does not sufficiently vet sellers on its platforms” and that its “counterfeit removal processes can be lengthy and burdensome, even for right holders that enroll in Amazon’s brand protection programs.”

Speaking out about the list at the time, Amazon called its inclusion a “purely political act” by the Trump Administration and “another example of the administration using the U.S. government to advance a personal vendetta against Amazon.”

Companies that are identified on the annual USTR list are not subject to financial penalties or regulatory oversight. Instead, the USTR’s list is used to encourage foreign entities and nations to crack down on piracy and counterfeiting. Nonetheless, being name-checked is generally considered to take a reputational toll in the individual company, particularly entities that are looking to position – or reposition – themselves to shed perceptions that their websites are riddled with fakes – a key to gaining bigger customer bases and traction among potential brand partners, while also taking market share from global competitors.

No mention has been made in this year’s list or by the USTR about how Amazon managed to avoid being named.