In what has proven to be a striking development over the past several months, the rise of the non-fungible token (“NFT”) has captivated the art world and have since entered the world of fashion, creating a market where digital versions of garments and accessories that are linked to unique blockchain-hosted tokens are increasingly coming front and center, and an influx of marketplaces aiming to cater to interested consumers. With the sheer success of NFTs in the art world, the adoption of these relatively novel digital assets by fashion industry entities seemed inevitable, and they have quickly infiltrated everything from streetwear and high fashion to footwear and the beauty space.

Amid this blockchain-enabled revolution, key moments stand out. For example, in March auction house Christie’s sold “The First 5000 Days,” an NFT collage by American digital artist Beeple for the cryptocurrency equivalent of $69 million. RTFKT (pronounced “artifact”) has also made a new for itself by way of its hot-selling digital sneakers and recently, a digital “Metajacket” jacket that sold for upwards of $125,000. Following the debut of these headline-making NFT-linked artworks in the market early this year, global luxury giants and fashion start-ups have similarly started looking to NFTs as a way to attract digitally-connected consumers and potentially generate revenue. There is revolutionary currency in NFTs and other forms of digital fashion (particularly for emerging designers and fledgling businesses), after all, as both types of digital assets allow newcomers to prosper outside traditional industry parameters.

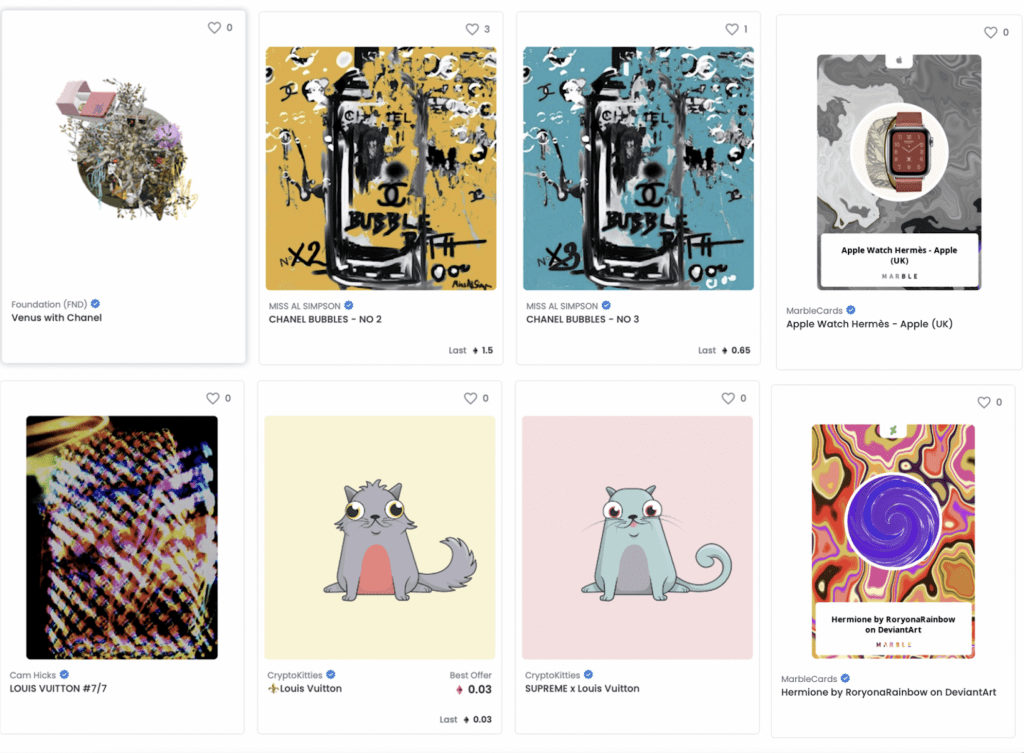

All the while, marketplaces are launching (quite successfully in cases like OpenSea, which nabbed a valuation of $1.5 billion in July, and facilitation two million transitions in August, totaling $3.4 billion in trading volume for the month) specifically to capitalize on this growing demand for buying and selling NFTs. But given that NFTs are still relatively new, regulation in this area is still evolving. Given the quickly-changing nature – and the readily-growing size – of the NFT market, it is paramount to understand all the legal considerations when launching an NFT marketplace, including documentation, intellectual property, and other legal concerns, as well as overarching legal implications of this new technology.

Essential Legal Documentation for NFTs

Company Formation – Launching an NFT marketplace? It is highly recommended that before doing so, the marketplace founders form a corporate entity first, as this offers the most robust liability protection for business owners and shields personal assets from business obligations. Additionally, a corporate entity provides greater ability – and credibility – when seeking financing from external sources and more flexibility to accommodate growth. To begin down this path, a company must be formed and registered correctly.

Terms of Service – A company’s terms of service act as the governing legal contract between the company and its users, and thus, serve as essential legal documents. When well-drafted, they will protect the company and limit its overall liability, implement an arbitration process, and set up an indemnification framework that will cover the company in the event of any disputes.

For NFT marketplaces, putting these protections in place is vital. In contrast to SaaS or another digital product, in which a company directly provides a service to its users, NFT marketplaces usually consist heavily of goods created by third-party users, and interactions and transactions between users. Therefore, there is a higher probability that misconduct by one user will negatively impact another. In that situation, the company or the marketplace is easy to blame for anything that goes wrong, making relevant terms of service particuarly critical.

Code Of Conduct – Given the predominance of user-generated content in NFT marketplaces, NFT marketplaces are generally encouraged to include extra layers of legal restrictions specifically in the form of community standards (otherwise known as a code of conduct) to govern interactions on the platform.

Privacy Policy – Finally, privacy policies are legally mandatory. A company is legally required to disclose its data collection and use practices, among other legally required disclosures. Depending on the applicable privacy law framework (e.g., GDPR, HIPAA, CCPA), additional disclosures may also be needed.

Intellectual Property Considerations

When creating an NFT marketplace, it is vital to allocate intellectual property rights between the artists/creators, collectors/purchasers, and other involved parties fairly and effectively. Without an effective allocation of intellectual property rights in place, operators risk undermining the legitimacy of their marketplace. (It is worth noting that acquiring an NFT does not automatically transfer ownership of the original work and corresponding intellectual property rights to the buyer unless otherwise specified by the creator; ownership of the copyright in an original work, including an NFT, for instance, vests in the creator of the original work.)

The specific allocation of intellectual property rights that takes place when a party acquires an NFT from its creator is typically determined in advance by the creator. Nonetheless, marketplace operators should keep in mind that overly aggressive transfers of creators’ rights may turn away artists and other creators from utilizing a marketplace. In contrast, not allocating sufficient intellectual property rights to collectors, the company, etc. will mean that the involved parties will not have the right to carry out their role or function in the marketplace.

Securities Law Considerations

Following the internationally coordinated crackdown on the initial coin offering (“ICO”) craze that culminated in the Telegram payment platform’s shutdown and return of $1.3 billion in ICO proceeds, issuers of NFTs and NFT marketplaces would be smart to avoid falling into the same potholes as their ICO predecessors. Wishful thinking will not prevail over securities regulators, particularly if retail investors lose all or a material part of their investment.

While each NFT should be analyzed for compliance based on its specific characteristics and the methods it monetizes, NFTs that underly collectibles (such as individual pieces of artwork) arguably should not be deemed to be securities. Instead, these NFTs are essentially finished products whose value is determined at a sale made directly to a buyer. Moreover, for NFTs representing a specific underlying asset or collectible, there is typically no expectation or need for a third party to extend organizational efforts that will enhance the value of the NFT, the sine qua non of an “investment contract” outlined by the U.S. Supreme Court (commonly referred to as the Howey test).

This logic has been previously supported by the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission. In 2019, the securities and stock market regulator published a digital securities “framework” document, where it stated that “[p]rice appreciation resulting solely from external market forces (such as general inflationary trends or the economy) impacting the supply and demand for an underlying asset generally is not considered ‘profit’ under the Howey test.” Therefore, the reasoning goes that the fact an NFT can rise and fall in value does not make it a security.

However, promoters of NFTs would be wise not to take this to the bank. Technological developments driving demand for NFTs could lead to a whole new world of derivative digital property rights that fail other Howey test prongs. The tokenization of insurance coverage and the after-market, for example, provides a notable example – artists selling rights to future proceeds on a secondary market in one form or another.

For any issuer of an NFT, an analysis must establish that a specific NFT is not security nor making a market in a security that would require registration or an exemption from registration under U.S. securities laws. Similarly, NFT marketplaces need to ensure that they are not required to register as a securities exchange or alternative trading system and broker-dealer.

Still yet, issuers of NFTs must take care not to market their NFTs for potential appreciation, profit, or dividends. The mere marketing of an NFT could transform it from a non-security into a security. Also, issuers should avoid (and NFT marketplaces should prohibit and prevent their users from): (1) Marketing an NFT as part of a fundraising effort to build a network or platform for future sales; (2) engaging promoters, sponsors, or third parties to drive the NFTs’ appreciation; and (3) enticing purchasers with the prospect of capital appreciation of the digital asset or profit linked to the efforts of the creator or other third party.

Taxation

Finally, there are additional legal implications to consider when it comes to NFT marketplaces, including taxes. In general, the IRS considers NFTs, like any other digital asset, to be “property,” and anyone engaged in their sale or purchase could be obligated to pay sales tax, losses, and capital gains taxes on them. Therefore, NFT marketplace should have mechanisms in place for collecting and remitting sales taxes and documenting sale prices, commissions, and other fees accurately.

From a tax standpoint, NFT marketplaces may also have to deal with different jurisdictions’ regimes, thereby, requiring heightened insight.

What Does the Future Hold for NFTs?

With the current proliferation of NFTs and NFT marketplaces, which shows no sign of letting up any time soon, NFTs are positioned to allow artists and creators to monetize their work and create new revenue streams that were previously unimagine. At one point, NFT fashion items, for instance, were dismissed as a fleeting fad, but in the time since, these blockchain-based assets have secured the stamp of approval from the world’s top luxury houses. Gucci, for one, sold its first NFT on June 3, 2021, offered as part of “Proof of Sovereignty,” a Christie’s-curated NFT sale that launched on May 25.

Other brands have also started experimenting with NFTs, using the tokens to unlock new digital products, distribution models, and monetization strategies. A couple of years ago, Nike patented the process behind its Crypto Kicks, which combined the use of NFTs with the ability to collect and customize sneakers.

All the while, many others view the current NFT craze as a bubble, with some investors buying NFTs as a speculative investment in hopes of flipping the tokens at a much higher price to make a quick profit. However, given the potential application of NFTs and underlying blockchain technology to a variety of real-world transactions, such as real estate, art and collectibles, retail, finance, and others, this tech trend is likely only at the very start of the possibilities for what NFTs can be used for in the future.

Catherine Zhu is a leading business, commercial, and privacy lawyer with Foley & Lardner LLP, where her practice focuses on complex commercial agreements, licensing, data sharing, revenue growth, business expansion, legal process optimization, and data privacy.

Louis Lehot is an emerging growth company, venture capital, and M&A lawyer at Foley & Lardner in Silicon Valley, where he provides entrepreneurs, innovative companies, and investors with practical and commercial legal strategies and solutions at all stages of growth, from the garage to global.