“You can relate NFTs to clothing in new and interesting ways,” digital artist Mike Winkelmann, better known as Beeple, told TechCrunch recently, reflecting on the potential uses of non-fungible tokens – or “NFTs” – within the sweeping landscape of digital art (and commerce). Thanks to the March 11 auction at Christie’s that saw his “First 500 Days” compilation sell for nearly $70 million, Charleston, South Carolina-based Winkelmann is now one of the posterchildren of the recent boom in NFTs, which have been experiencing remarkable gains in demand and value over the past several weeks, in particular.

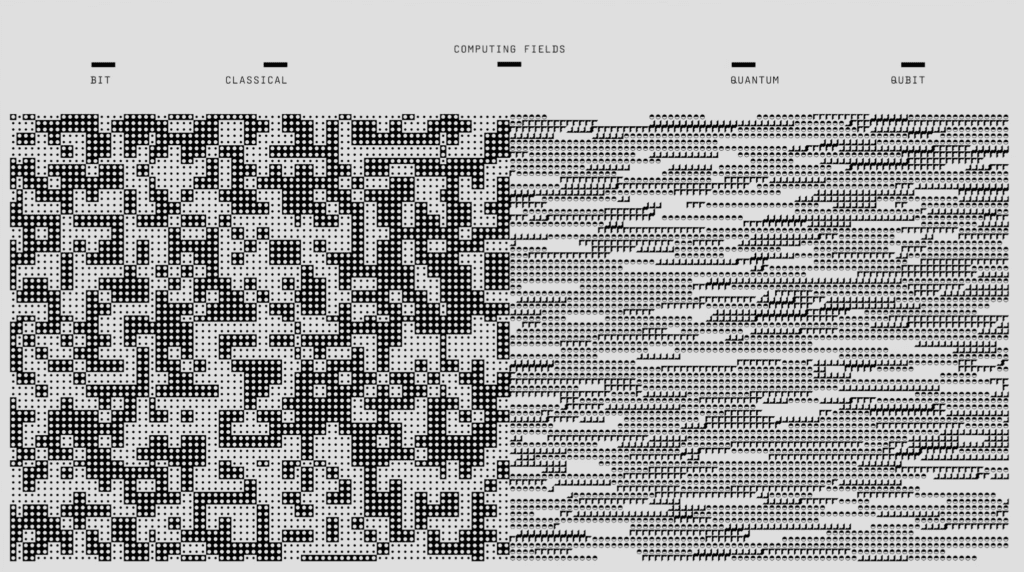

NFTs are unique crypto tokens that consist of software code that essentially acts as a digital certification of ownership rights that can be attached to often-digital assets. In addition to documenting ownership and changes in ownership by way of an Ethereum blockchain-run ledger, NFTs, “like any software application, can be programmed to include a variety of other applications and functionality, including linking the NFT to another digital asset,” according to Latham & Watkins attorneys Calum Docherty and Christian McDermott.

Digital Assets and Physical Ones, too

In addition to tying an individual NFT to a specific digital asset, such as a Beeple artwork or a digital dress like the one that The Fabricant created in 2019, TechCrunch’s Leigh Cuen recently reported that fashion designers like Schirin Negahbani are going a step further and “creating NFTs that represent actual clothing.” Meanwhile, toymaker Funko is enabling the buyers of its NFTs to redeem them for “exclusive, corresponding physical Funko figures.”

While “the tokenization of physical items is not yet as developed as their digital counterparts,” blockchain platform Ethereum states in a “use case” report that NFTs “can be used to represent ownership of any unique asset in the digital or physical realm,” and asserts that “there are plenty of projects exploring the tokenization of real estate, one-of-a-kind fashion items, and more.” And the application of NFTs to the physical world is certainly compelling. By way of the code that underlies NFTs, brands can chart – and share with consumers – the lifespan of a product, which could prove enticing if brands couple real-world or digital world add-ons by way of the smart contracts underlying NFT-connected products. It is relatively easy to envision brands linking in-store perks to online-acquired NFTs in order to drive a return to brick-and-mortar stores, for instance.

At the same time, such provenance-tracking NFT technology could prove to be a critical tool in the larger authentication process. (NFTs can authenticate ownership of a token itself, as well as the unique history of how that token was developed and associated with a creative work, but they cannot, alone, prove authenticity of the associated work).

NFTs and the Resale Market

The ability to tie NFTs to physical objects in order to track a product’s lifecycle is also enticing from a secondary market perspective. Early NFT-adopter Arianee, for one, is aiming to aid in a more seamless resale market by way of its “NFT digital passports for luxury goods,” which go so far as to digitize service history and repairs, a critical consideration for the likes of luxury timepieces and issues of authenticity (as we know from Rolex), as well as for handbags, judging by arguments made in the Chanel v. What Goes Around Comes Around case.

Arianee believes that this type of tech can play an important role in the burgeoning luxury resale market and “unlock a new paradigm of digital value on top of each item” in the process.

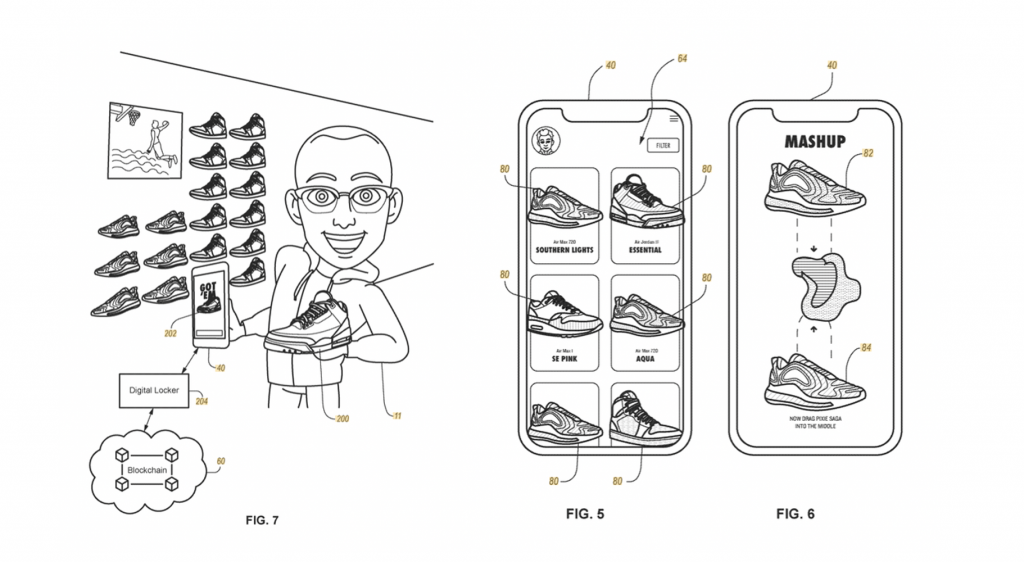

In terms of the secondary market, the potential uses of NFTs could play out in a number of ways, a number of which Nike alluded to in the utility patent that it received in December 2019 for a “system and method for providing cryptographically secured digital assets.” One of one the most striking: the role of resale royalties.

The Beaverton, Oregon-based sportswear giant’s patent works something like this: Each time a pair of physical shoes is created by Nike, the company also generates a corresponding cryptographic digital asset – i.e., a “CryptoKick” NFT – which consists of a Unique Product Identifier and a digital version of the shoe. When a consumer purchases “a real-world pair of shoes from a registered seller,” he/she can unlock and access the CryptoKick. The Nike NFTs allow consumers to “securely trade or sell the tangible pair of shoes” and/or digital versions. But more than that, the Nike patent states that the information embedded in the CryptoKick tokens allows for the “breeding of a digital shoe with another digital shoe to create ‘shoe offspring,’” and depending on Nike’s specific manufacturability rules, that offspring may to be “custom made as a new, tangible pair of shoes.”

This process is governed, however, by the “real-world manufacturing restrictions” that are included in the Nike NFTs’ smart contracts. One such restriction could come into play if/when virtual sneakers are “breeded,” and ensure that any successive generations are “tied back to the original, real-world [Nike] shoe (e.g., wholly or partially; by percentage of genotypic contribution, etc.) via encryption key to the originally associated virtual product.” As a result, Nike could mandate that it automatically receive a percentage of the price that any “breeded” shoes are sold for – either digitally or in tangible form.

“Unlike the physical markets where brands and designers lose out from secondary market sales,” both in terms of cash and maybe even more importantly, control, Nasdaq recently reported that “NFTs mean that royalties can be programmed to apply for the entire lifetime” of a digital asset. So, depending on the provisions of an NFT’s smart contract, “each time a digital fashion piece changes hands, the creators always get to take their share of the royalties, enforced automatically through programming on the blockchain.”

As Dror Poleg explained in an article about NFTs and the future of work, “The Ethereum network enables developers to set up smart contracts, [which] are essentially bits of code that can specify a series of actions that happen as a result of specific triggers.” For example, “A smart contract can specify that every time the flying cat gif is resold, the artist that designed it will get 10 percent of the sales price.” Even if the flying cat gif NFT “is now owned by someone who bought it from someone who bought it from the original creators,” Poleg claims that “the smart contract will ensure that the original creator gets compensated each time his work appreciates in value and is being resold.”

With this in mind and given the increasing attempts to associate NFTs to physical objects, there is a chance that brands will look to add specific resale royalty provisions to the terms of any acquired NFTs, thereby, extending such resale royalty principles (and the corresponding smart contract code) to certain physical goods from the outset by way of corresponding NFTs – whether those goods be limited run Nike sneakers, which are increasingly demanding record prices at footwear-centric auctions, investment-grade handbags, or particularly valuable jewelry designs.

Resale Restrictions

Another potential use of the “real-world restrictions” that can be embedded in the code of NFTs and associated with physical goods, as cited in Nike’s patent? Terms that seek to specify what types of sales are permitted in a secondary market scenario. Such terms could – at least in theory – mirror the relatively new language that Hermès includes on its sales receipts in order to prohibit buyers from reselling their purchases in certain capacities. As Pursebop revealed in December, the Paris-based luxury goods brand began adding language to its receipts in or around July 2020 that states that as a term of sale, “The customer represents and warrants that they are purchasing Hermès product in our boutiques for their personal use. Therefore, you agree you will not, directly or indirectly, resell Hermès products purchased in our boutiques for commercial purposes.”

The receipt provision is likely a response to burgeoning resale businesses that operate exclusively to procure hard-to-get handbags and accessories, and then offer them up to consumers – often at a premium. Given the hoops that it notoriously requires consumers to jump through to get some of its most coveted bags, Hermès is a primary target of such resale operations. Moving past paper receipts, such a restriction could be included in an NFT’s smart code and tied to an Hermès Kelly bag, along with other ownership details about the bag, and even repair history information given that Hermès’ emphasis on its “maintenance and repair” services.

However, unlike in the automatic royalty scenario, the implementation of such a resale limitation condition beyond blocking the transfer of a token linked to a handbag (as distinct from the actual bag, itself) would require an additional step – or multiple steps – on the part of the seller-company. And while such a “restriction would presumably have legal effect so long as the buyer and seller [agree] to the governing terms,” according to Davis Wright Tremaine attorneys Lance Koonce and Sean M. Sullivan, “the NFT smart contract, itself, cannot enforce that provision.” This means that the seller – Hermès, for instance – “would have to resort to traditional methods of enforcement (e.g., demand letters, litigation)” should it find that buyers are breaching the terms that preclude them from reselling products in a certain capacity, such as part of a larger commercial resale business.

Again, it is still early days when it comes to the use and development of NFTs and certainly, the application of NFTs to physical goods, but given the enduring interest from brands across industries in finding digitized and immutable tracing, ownership, and ideally, authenticity-affirming technologies (LVMH, for instance, have been working on a blockchain-centric authenticity service for a few years), and given the unrelenting rise of the resale market, which impacts original manufacturers in more ways than one, brands will likely continue to explore how they can make such tech work for them.