The push to prolong the lifespan of the garments and accessories that have already been released into the market is readily gaining steam. Back in 2019, Arc’teryx made headlines when it launched Rock Solid, an initiative that sees the upscale outerwear brand buy back pre-owned products from its customers, refurbish them, and sell them on a special section of its website. Other brands, such as Eileen Fisher, Levi’s, North Face, and Patagonia, have also adopted sustainability-centric ventures, such as circularity ventures, in order to keep pre-owned products bearing their name in the market for longer and to tap into the growing resale segment of the marketplace in the process.

In a couple of other examples of the enduring embrace of circularity by brands and other industry players, London-based luxury fashion retailer Farfetch announced in early 2021 that it had partnered with product aftercare company The Restory to offer consumers the opportunity to have accessories from their closets repaired and restored. Called Farfetch Fix, the venture “offers bespoke repairs – masterfully worked on by specialist artisans – to return your designer shoes, handbags, and small leather goods to their former glory.” By way of Farfetch’s e-commerce site, consumers can “book a collection,” at which point the product will be taken to The Restory’s atelier, where repair services will be proposed, and a quote will be shared with the consumer. Ultimately, the product will be shipped back to its owner in its newly-restored state.

More recently, Nike revealed that as part of a new “Refurbished” initiative, it will take “like new (maybe worn for a day or two before being returned), gently worn (a little longer) and cosmetically flawed (think: something like a small snag that happened in manufacturing)” sneakers that consumers return, “tidy them up,” and sell them at a number of its stores across the U.S., alongside brand-new wares.

To date, it appears that most of the growing number of circularity-centric efforts are primarily coming in one of two ways: 1) brands are buying back, revamping, and reselling their branded goods (oftentimes with the help of buyback-and-resell companies like Trove), or 2) third parties – such as Farfetch or The RealReal by way of its in-house “suite of repair services” – are refurbishing designer goods without the underlying brands’ involvement.

While the goal of these efforts – no matter how they are carried out – is largely the same and is aimed at prolonging a product’s shelf life, the distinction between brand-authorized repair and resale scenarios, and those that are completed exclusively by third parties is not insignificant. In fact, a number of lawsuits demonstrate that the practice of modifying – or potentially even just refurbishing products – and then selling them without the original brand owner’s approval and/or without sufficiently communicating such changes to consumers can give rise to legal complications. This raises questions about the rise in unapproved repair and refurbishment efforts.

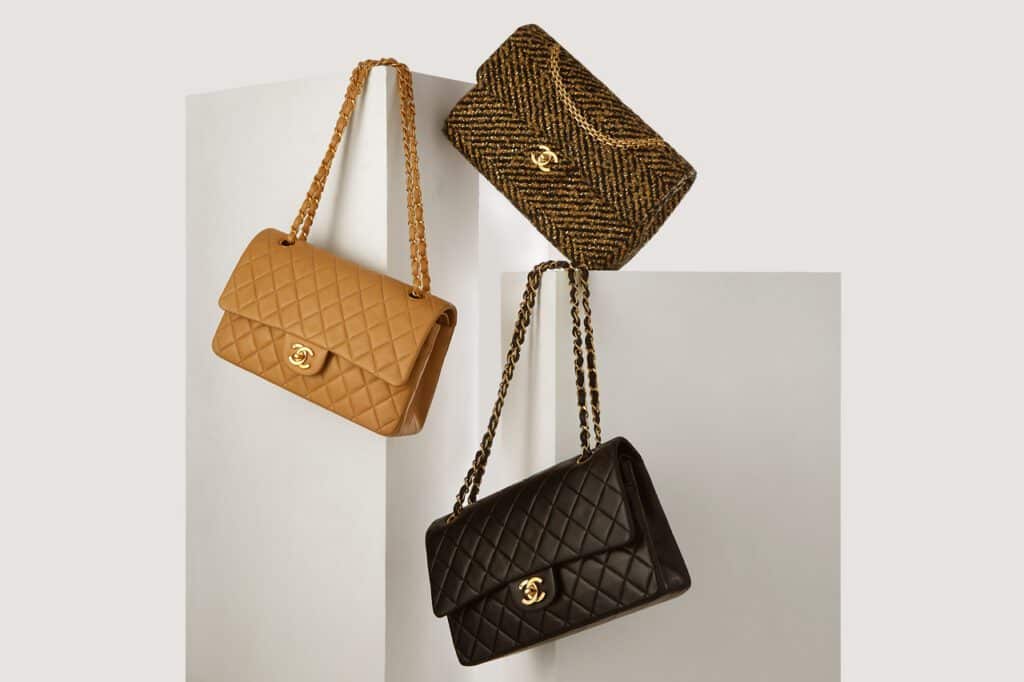

To date, refurbishment has ruffled feathers in instances where trademark-bearing products are modified and then subsequently sold without the original manufacturer’s authorization and/or without proper disclosure to alert consumers of such modifications. Chanel, for instance, has argued in the ongoing case that it filed against What Goes Around Comes Around (“WGACA”) that the luxury resale company enlisted a third-party company to repair and/or refurbish Chanel products before offering them for (re)sale. Because WGACA allegedly failed to alert consumers about the altered state of the bags, it may have misled consumers about the nature of the Chanel products. (WGACA has since argued that the “limited ‘sprucing up’ that [was carried out by Rago Brothers Shoe & Leather Repair] … never resulted in a Chanel product [being] ‘so repaired, reconditioned, or altered to have lost its identity as a genuine Chanel item.”)

(In addition to taking issue with WGACA’s refurbishment in the case, counsel for Chanel has filed trademarks applications for registration with the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office on an intent to use basis, including one for its name and another for its double “C” logo, for use in connection with the “cleaning and repair of fashion and fashion accessories.”)

Nike made something of a similar argument in the since-settled case that it filed against MSCHF over the Brooklyn-based art collective’s “customized” Satan Shoes.

The claims made in these cases (and others) stand to potentially complicate the push to prolong the lifecycle of products, particularly if those modified products end up finding their way into the $30 billion-plus luxury resale market.

First Sale?

“Entrepreneurial activity in the market for used and repaired goods should be encouraged,” Annette Kur, an affiliated research fellow in Intellectual Property and Competition Law at the Max Planck Institute for Innovation and Competition, asserted in an Oxford article. Yet, she notes that at the same time, “Problems may arise” – and in fact, have arisen – “where trademark-bearing products are offered for sale after repair or refurbishment by third parties.” And while the First Sale Doctrine clearly allows for the resale of a trademark-bearing product once the manufacturer releases that product into the market, Kur notes that this trademark tenet “does not apply when the condition of the product was changed after that initial sale,” which is precisely what is at play in at least some repair and refurbishment scenarios.

As for whether refurbished luxury goods fall within the bounds of the First Sale Doctrine, courts will generally look at whether any of the modifications are “material.” In other words, if the process of refurbishing or repairing the product materially changes that product, then the First Sale Doctrine likely does not apply. With that in mind, certain services – such as simply cleaning a leather bag, re-heeling a stiletto, or repairing damaged stitches on garments or accessories – likely do not raise issues from a First Sale perspective, meaning that a party is free to make such adjustments and resell the product without needing authorization from the trademark holder.

The balance may shift in the other direction when it comes to permanently altering the original strap on a bag, for instance, or replacing a zipper with a new one – and selling these goods en masse. And courts would certainly find a modification to amount to a “material” change in the case of MSCHF, for instance, which injected red ink and a drop of human blood into the otherwise clear heels of a pair of Nike Air Max 97s, and in the case that Rolex filed against watch-seller BeckerTime. (These instances might be the type that fall within the camp of goods that Chanel referenced in a letter to the court in the WGACA case, citing Judge Nathan’s decision in the Hamilton watch case, in which he held that it is “possible to imagine a case ‘where the reconditioning or repair would be so extensive or so basic that it would be a misnomer to call the article by its original name, even if the words ‘used’ or ‘repair’ were added.”)

The Role of Resale

As a result of the “material difference” exception to the First Sale Doctrine and given the rapid rise and ever-expanding reach of the resale market, which makes pre-owned luxury goods more affordable and more easily assessable than ever before, at least some brands have been prompted to call foul from a trademark perspective when goods bearing their trademarks are refurbished and then sold without their authorization, thereby, preventing them from controlling the quality of those products.

While it is unlikely that one-off modifications by consumers are likely to give rise to rampant legal issues, in terms of how unauthorized third-party modifications may play out in the future, it is easy to see potential issues down the road if/when those initially-authentic but materially altered products – whether it be a Louis Vuitton bag refurbished courtesy of Farfetch or altered Swoosh-bearing MSCHF sneakers – enter into the marketplace in a resale capacity, and thereby, cause confusion among consumers about the underlying nature of the product, particularly when any modifications are not immediately known by the reseller and therefore, not mentioned in a product listing. (This is what is going on, at least in part, in the Chanel v. WGACA case).

Ultimately, issues of modification will likely continue to come up as “the lifespan of fashion products is being stretched as pre-owned, refurbished, repaired and rental business models continue to evolve,” McKinsey stated in a 2019 fashion industry report, and especially as consumers “demonstrate an appetite to shift away from traditional ownership to newer ways in which to access product.” As such, the enduring adoption of resale models and the push for circularity by brands will require a careful “balancing of the interests of trademark proprietors, actual or potential competitors in secondary markets, consumers, and society,” Kur argues, and from a legal perspective, these issues are clearly coming under the microscope in the process.

*This article was originally published in April 2021, and was updated in January 2022 to note the outcome of the Rolex v. BeckerTime case.