Deep Dives

Armani made headlines earlier this month when an Italian court revealed that it is tied up in a labor matter after at least one of its suppliers used subcontractors that flouted national labor laws. In a court order released on April 5, the Court of Milan stated that one of Armani’s suppliers, Manifatture Lombarde, “used subcontractors in the Milan area that employed undocumented migrants for the production of Armani bags, leather goods, and other accessories,” subjecting these individuals to “particularly disadvantageous working conditions,” including requirements that they work a greater number of hours than the company officially declared and the payment of wages of between €2 and €3 ($3.25) per hour. (Reuters reported that not one but two of Armani’s suppliers, Manifatture Lombarde and Alviero Martini, are on the hook for subcontracting out the manufacturing of Armani accessories to third party companies without Armani’s knowledge or authorization.)

“In a ruling dated April 3, the court appointed a consultant for one year to work alongside managers [at Giorgio Armani Operations] to improve relations with suppliers,” the AFP reported. The court’s order – which comes amid a years-long effort by the Milan public prosecutors’ office to investigate the outsourcing of production by large groups in fashion and other industries to subcontractors that allegedly exploit workers – sheds light on rising regulatory attention to the workings of apparel brands’ supply chains. (Such attention is likely to increase further in coming years in light of ESG-centric calls for increased transparency about companies’ value chains.)

While fast fashion companies have traditionally been at the center of manufacturing-related disputes, the Armani case demonstrates that both the mass-market and high-fashion levels, alike, face difficulties when it comes to keeping tabs on their complex and often murky supply chains.

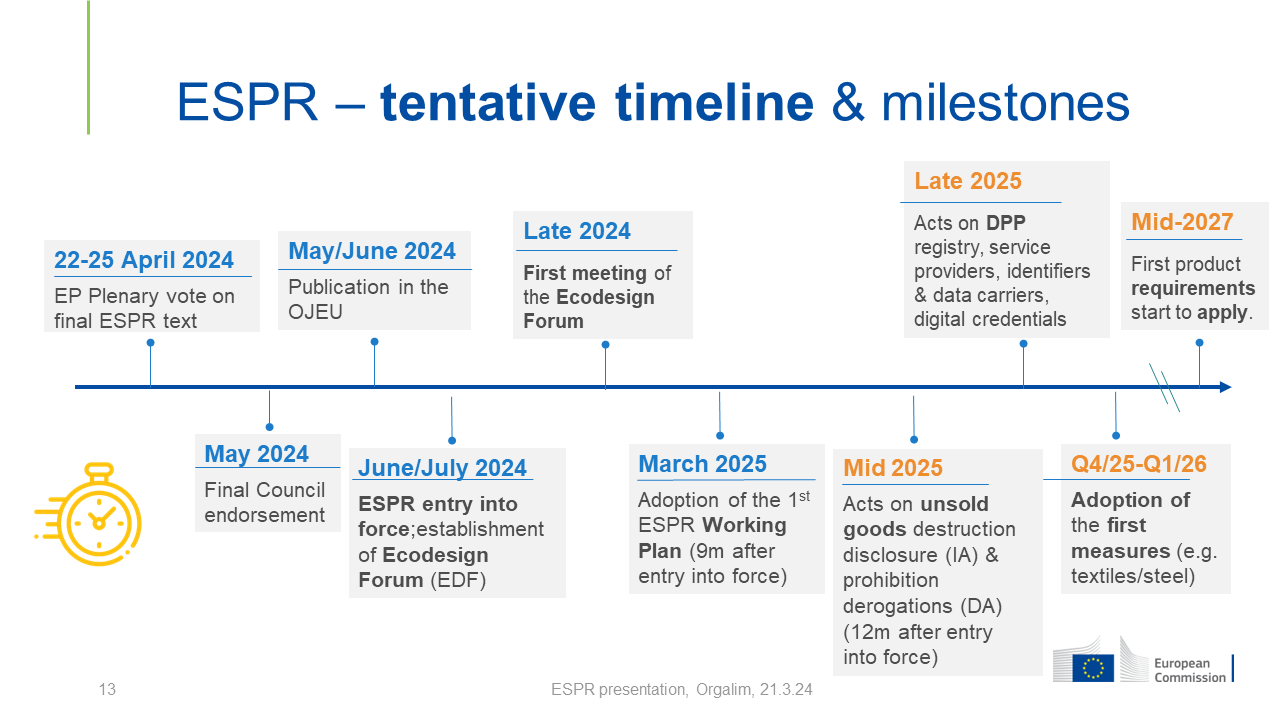

One element worth addressing here is the impending role of legislation in the European Union that aims to bring transparency to the products offered up in the apparel and textile segment. As part of a reworking of the existing Ecodesign Directive 2009/125/EC, the EU has proposed (and preliminarily passes) the Ecodesign for Sustainable Products Regulation (“ESPR”). The ESPR – a provisional agreement of which was adopted in December 2023 and adopted in April 2024 – “follows the same approach as the current Ecodesign Directive, which has been driving efficiency gains for energy-related products in the EU for over a decade,” according to the European Commission.

ESPR in a nutshell: The ESPR proposal “will apply to the broadest possible range of products and will use the successful ‘Ecodesign approach’ to set product-level requirements that not only promote energy efficiency but also circularity and overall reduction of environmental and climate impacts.” Aimed at ensuring the design of “more environmentally sustainable and circular products,” the ESPR will subject companies that put apparel products into the EU market to requirements regarding a product’s durability, reusability, upgradability and reparability, and the presence of substances that inhibit circularity.

> Products covered by ESPR: The legislation will enable rules to be set for any physical good placed on the market, or put into service, including intermediate products. Only a few sectors will be exempt, including food, feed, living organisms, certain motor vehicles, and medical products.

> Implementation of the ESPR’s rules: The ESPR sets a framework that will enable product-level rules to be set out in a second stage, through delegated acts, product by product or for groups of products if appropriate. The European Commission has stated that it intends to prioritize the introduction of requirements for certain product groups that it deems highly impactful. These include textiles, iron, steel, aluminum, furniture, tires, paints, and chemicals, as well as certain energy-related products and electronics.

> Digital products passports: The ESPR introduces a requirement that companies make use of digital product passports to provide information on the sustainability credentials of products via QR code to consumers, regulators, and other businesses in the supply chain. (More about this below.)

> Unsold goods: The ESPR also specifically bans the destruction of unsold apparel, related accessories, and footwear beginning two years after the legislation’s entry into force (six years for medium-sized enterprises). In the future, the Commission says it “may add additional categories to the list of unsold products for which a destruction ban should be introduced.”

The state of the ESPR: EU Parliament voted on and adopted the legislation during a plenary session on April 23, 2024 with 455 votes in favor, 99 against, and 54 abstentions. The European Council now must formally approve the ESPR before it can be signed into law.

One particularly notable side effect of the proposed ESPR is the mandatory introduction of digital products passports (“DPPs”), which will, at least in theory, bring about heightened transparency when it comes to companies’ products and their supply chains.

In addition to providing consumers with greater access to information about the content, repairability, and recyclability of specific apparel products, the European Commission says that the DPP scheme “should also help public authorities to better perform checks and controls,” presumably bringing benefits in terms of supply chain oversight and tracking.

Since the ESPR and the corresponding requirements around the adoption of DPPs is expected to impact most companies in the coming years, apparel industry entities should start paying attention now, if they are not already doing so. However, companies currently face high uncertainty as many critical elements of the impending DPP requirement remain open, including the scope and process for implementation. For instance, while the European Commission plans to roll out the implementation of the DPP mandate by product group, a framework on how it will prioritize the different product groups beyond its initial list of “priority” products has not been released.

The lack of certainty makes it difficult for companies to determine exactly how and when the ESPR – and DPP-specific rules, in particular – will apply to them. Nonetheless, for companies are looking to get ahead of the impending implementation of ESPR, the World Business Council for Sustainable Development says that companies “can benefit from taking early action now as they can influence regulation, improve compliance and resilience, unlock investment synergies, and increase transparency.”

Among the key actions that the World Business Council for Sustainable Development recommends for relevant entities looking to get a jump on ESPR preparation are …

(1) Start assessing the company’s current data availability, identify gaps, and gather missing data using the proposed ESPR, Battery Regulation, international and European standards, and circular economy standards as a framework;

(2) Enable your organization across departments to adapt to the coming DPP implementation (this includes enabling transparency while maintaining confidentiality; for example, companies must determine how they can share enough information to improve circularity of products while ensuring the enduring protection of IPRs and commercially sensitive information); and

(3) Plan for changes in the company’s tech setup to allow for implementation of the DPP mandate (this includes choosing a DPP data storage option).

TLDR: Life cycle assessment software provider Ecochain notes that while the ESPR will pose Ecodesign criteria for as many products as possible, in the next few years, it will be implemented for “only a limited range of energy-intense products.” As such, the first step for companies should be to identify whether – and which – of their products fall within the realm of “priority” products. These include: iron, steel, aluminum, textiles (notably garments and footwear), furniture, tires, detergents, paints, lubricants and chemicals.