Condé Nast is slamming the right of publicity lawsuit that nearly 50 models filed against it and Moda Operandi last fall for allegedly using photos of them walking in the Spring/Summer 2020 runway shows in order to sell runway garments and accessories without their authorization. On the heels of the high fashion retailer and the magazine publisher pushing back against the models’ claims in respective motions to dismiss, and a New York federal court stripping down the case, Condé Nast is trying to get the rest of the case – including the plaintiffs’ right of publicity and unjust enrichment claims – tossed out.

In the answer that it filed on November 13, Condé Nast argues – by way of seventeen affirmative defenses – that the model plaintiffs’ remaining causes of action against it should be dismissed. Among other things, Condé Nast argues that the models’ claims are barred by the First Amendment, preempted by federal copyright law, and are otherwise not viable because it did not use their images or likenesses “for advertising purposes, or for the purpose of trade, or for any other commercial purpose.” Instead, the New York-headquartered media company claims that it used the runway photos “in connection with matters of public interest, public concern, and/or [matters that are] newsworthy,” which amount to uses that are permitted by the law.

Beyond the affirmative defenses, Condé Nast sets out a single counterclaim, alleging that on September 4, 2020, the model plaintiffs commenced this lawsuit, despite their “lack of any substantial basis in law or fact,” and in furtherance of an attempt to “inhibit [its] exercise of the constitutional right of free speech in connection with an issue of public interest, namely fashion reporting.”

The primary issue, according to the Vogue publisher, is the editorial nature of its runway coverage. By way of its Runway vertical, Condé Nast says that it provides “comprehensive fashion runway editorial coverage,” including an “archive repository [of imagery and reviews] for the fashion industry and interested readers.” Such editorial – versus commercial – use of runway imagery stands in the way of the models’ ability to make plausible right of publicity claims, per Condé, as “it is well-established that … recovery under New York’s right of publicity statute is strictly prohibited unless a person’s likeness is used for trade or advertising purposes.”

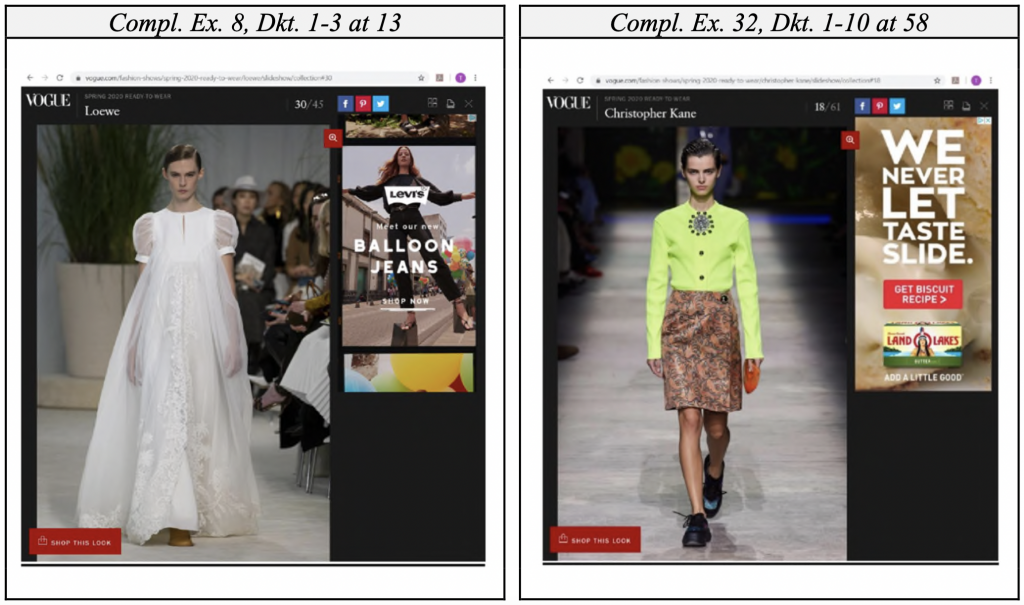

Citing the court’s September memo and order, in which it dismissed all of the models’ false endorsement claims against CondéNast, more than a dozen of the models’ false endorsement claims against Moda Operandi, and most of the models’ right of publicity claims against both defendants, Condé Nast states that Judge Colleen McMahon already found that the runway coverage “is a work of fashion journalism,” which is not changed by the fact that “like every fashion magazine, [it] happens to contain advertisements.”

(Condé notes that the models do not take issue with the placement of banner ads that appear “in proximity to their likenesses” in the runway section of its site, such as those from “Otezla, Burberry, Hourglass cosmetics, and Hermès,” and instead, focus solely on “the inclusion of very small hyperlinked boxes with the words, ‘SHOP THIS LOOK,’ that if clicked, led visitors to Moda’s website.”)

By bringing this case against it “for the purpose of inhibiting and interfering with [its] exercise of free speech rights regarding an issue of public concern,” namely, the seasonal runway shows, and thereby, “forcing [it] to defend itself against litigation arising from the exercise of First Amendment-protected activity,” Condé Nast argues that the models are actually in the wrong.

“This is a classic SLAPP suit,” according to Condé Nast, which claims that the models “commenced and continued their meritless right of publicity claims against [it] with full knowledge that their claims lack any substantial basis in law or fact.” Even after Condé Nast counsel “repeatedly made clear to counsel for the [models] that their right of publicity claims have no basis,” the publisher contends that they, nonetheless, “persisted in filing and continuing this action, causing [it] to expend significant costs and fees to defend its First Amendment-protected rights.”

“This kind of attack on the exercise of free speech” is precisely the type that is prohibited by anti-SLAPP statutes, which apply to lawsuits that “target ‘[a]ny communication in a place open to the public or a public forum in connection with an issue of public interest’ or ‘any other lawful conduct in furtherance of the exercise of the constitutional right of free speech in connection with an issue of public interest’ with the term ‘public interest’ defined ‘broadly’ to ‘mean any subject other than a purely private matter.’”

The case at hand falls neatly within that framework, per Condé Nast, as “Vogue is a public forum” and fashion news is a matter of public interest. Specifically, it asserts that the right of publicity claims that the models set out in their complaint are without legal basis because “New York courts recognize that there is a well-established ‘newsworthiness’ exception to liability under the right of publicity statute, and that exception has been held to apply to fashion reporting like the Runway Editorial at issue here.”

By commencing a lawsuit that is aimed at “inhibit[ing] the exercise of free speech and harass[ing] a publisher by forcing [it] to spend money to defend against [such a] baseless suit,” Condé Nast argues that the models have violated New York’s anti-SLAPP statute, and unless they are “held accountable for their tortious activity, the purpose of the Anti-SLAPP Law will be frustrated and it will be open season on New York publishers forced to defend against lawsuits that inhibit their exercise of Constitutionally-protected free speech rights.” As such, in addition to tossing out the plaintiffs’ claims, Condé Nast is seeking damages, including its attorneys’ fees, as well as compensatory and punitive damages.

The case is Champion et al., v. Moda Operandi, Advance Publications d/b/a/ Conde Nast, 1:20-cv-07255 (SDNY).