Remember Cult Gaia’s Ark bag, the bamboo handbag that flooded Instagram feeds in recent years, putting the budding Los Angeles-based womenswear brand on the map, and that gave rise to no shortage of legal issues – from a lawsuit involving Steve Madden to a quest by the brand to claim exclusive trademark rights in the look of the bag, itself. Well, that trademark back-and-forth is still underway before the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (“USPTO”), more than three years after Jasmin Larian, LLC – aka Cult Gaia – first filed its application for “the configuration of a three-dimensional handbag.”

Following several protracted rounds before the USPTO, in which examining attorneys for the trademark body have pushed back against the registration of the Ark bag for a number of reasons, including because the “it” bag is functional in nature and fails to operate as a trademark, Cult Gaia received yet another “no” from the USPTO this month.

In a newly-issued Final Office Action dated October 16, USPTO examining attorney Matthew Ruskin states that the “functional product design refusal” previously asserted by the USPTO has been withdraw in light of Cult Gaia’s response to the relevant Office Action, including the brand’s arguments about the elements of the bag could be positioned differently. However, hardly an across-the-board win for Cult Gaia, Ruskin asserts that the larger “refusal of registration is hereby made final because the applied-for product design is generic.” In other words, it is so common in the industry or “consists of a shape … that conforms to a well-established industry custom” that it “does not function as a trademark to indicate the source of applicant’s goods and to identify and distinguish them from others.”

Beyond that, Ruskin says that a separate refusal is “maintained and continued because the applied-for mark consists of a nondistinctive product design or nondistinctive features of a product design that is not registrable on the [USPTO’s] Principal Register without sufficient proof of acquired distinctiveness.”

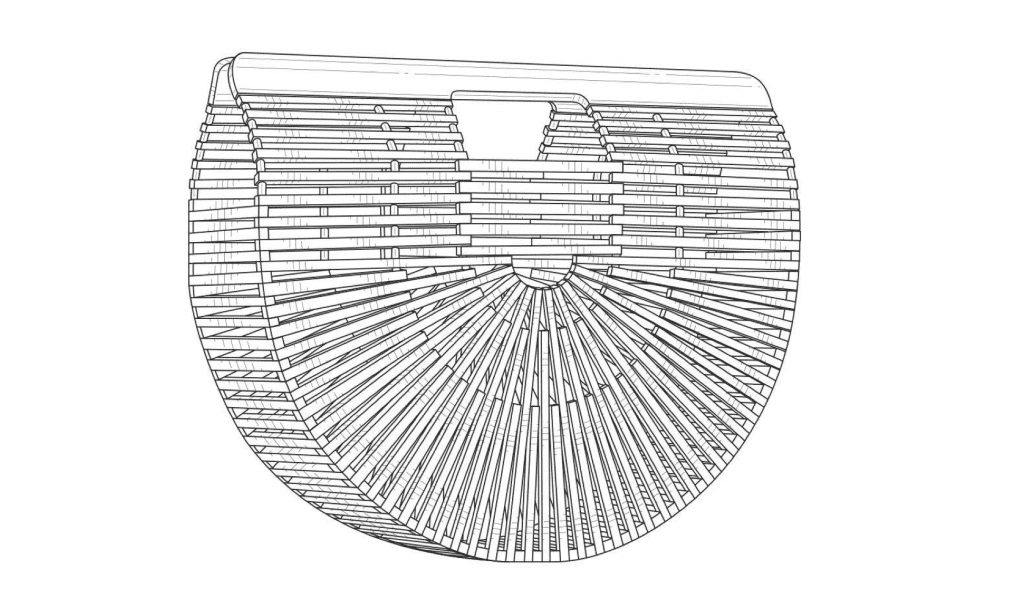

(According to Cult Gaia’s application for registration, that product design, and thus, the trade dress at issue, consists of “a distinct combination of: (1) a structured and flat front and back panels made of thin, uniformly-sized strips of rigid material; (2) arranged in an interlocking manner to form three concentric half circles creating a distinctive see-through sunburst design; (3) topped by horizontal strips and a handle made of the same material with a curved tapering cutaway; (4) a curved side panel made of interlocking pieces of the same material and in the same width as the pieces that make up the front and back panels; and (5) spacers in the form of circular beads that connect the handle pieces.”)

Speaking to the refusal on the basis that the design of the bag is generic, Ruskin asserts that the evidence presented in the matter at hand – including examples of lookalike “vintage” bags being sold on Etsy and an excerpt from “vogue.co.uk [that shows] that a virtually identical bag was featured in a fashion line in 2009, with press coverage of the related fashion show distributed to” consumers in the U.S. – “demonstrates that [Cult Gaia] seeks registration for a particular variety of ‘birdcage’ or ‘Japanese bamboo’ bag that is sold by a number of different retailers, that existed long before [Cult Gaia’s] date of first use” in January 2013.

The primary issue with such widespread use of the bag design by parties other than Cult Gaia is “not whether prior users of the design may assert trademark rights under the Lanham Act,” Ruskin notes, but instead, whether “consumers recognize [that the design] emanates from many different sources” and not just a single source. That is problematic, as in order to function as a trademark (and be eligible for registration as a trademark), the mark – whether it be a name, logo, product configuration, etc. – must be capable of identifying a single source and thereby, distinguishing the source of the goods of one party from those of others.

(Steve Madden made this argument in the declaratory judgment lawsuit it filed against Cult Gaia in March 2018 after receiving a cease and desist letter from the brand. According to Madden, Cult Gaia lacks trade dress rights in the bag design because it is “ubiquitous in the handbag market” (and thus, not indicative of a single source) and/or is merely functional and does not warrant protection under the Lanham Act. That case has since settled out of court).

In addition to shooting down arguments from Cult Gaia about “whether relevant consumers are aware that the design emanates from more than one source,” and about the admissibility/value of the evidence submitted in connection with such consumer awareness, Ruskin claims that Cult Gaia has failed to address “the probative value of [its] own website and informational material, which clearly identify the design as a ‘reproduction.’” That is significant, per Ruskin, as “an applicant’s own website and marketing material is probative and can be ‘the most damaging evidence’ in showing how the relevant public perceives a term.”

With this in mind, the examining attorney states that “the evidence in this case” specifically demonstrates that “the particular design of handbag for which applicant seeks registration was in use in commerce both decades before and immediately before applicant’s date of first use, that the style is recognized among buyers and sellers of vintage goods, and that the public—when confronted with applicant’s goods—understands that the particular design may come from a wide variety of sources.”

Moreover, Cult Gaia’s “own website, marketing material, materials included in the packaging of the goods, and statements to the press indicate that the bags are merely reproductions of a classic style,” which taken together means that “the relevant consumers of applicant’s goods will not view the design configuration as source-indicating, rendering the trade dress generic for the goods.” Therefore, Ruskin states that “the refusal to register under sections 1, 2, and 45 [of the Lanham Act] is hereby continued and made final.”

Turning his attention to the refusal on the basis that the Ark bag “consists of a nondistinctive product design or nondistinctive features of a product design that is not registrable on the Principal Register without sufficient proof of acquired distinctiveness,” Ruskin asserts that Cult Gaia has failed to prove that the design of the bag has acquired distinctiveness. (He cites Walmart v. Samara Bros., of course, in stating that “a product design can never be inherently distinctive as a matter of law; consumers are aware that such designs are intended to render the goods more useful or appealing rather than identify their source, [and] thus, consumer predisposition to equate a product design with its source does not exist).

In order “to show that a mark has acquired distinctiveness, an applicant must demonstrate that the relevant public understands the primary significance of the mark as identifying the source of a product or service rather than the product or service itself,” which is no small feat, and one that Cult Gaia did not accomplish here, according to Ruskin.

“In light of the above evidence,” which demonstrates that “the relevant consumers of the bag readily understand that [Cult Gaia’s] bag employs a common design with no features capable of distinguishing it from earlier productions,” Ruskin argues that Cult Gaia’s “sales figures, advertising expenditures, Instagram mentions, and press clippings do not demonstrate that [its] goods have become so distinct that the design alone points specifically to [its brand].” As such, he states that “the goods have not acquired distinctiveness and the final refusal under Sections 1, 2, and 45 is hereby maintained and continued.”

Not necessarily a done deal, Ruskin states that Cult Gaia has failed to adequately respond to outstanding questions previously raised in an Office Action, including “how many unique users visited pages on [its] website where” the Ark bag was listed as a “reproduction” or was referred to “as a ‘classic’ or Japanese design, or using similar language?” And how many bags did Cult Gaia sell and/or ship to retailers that contained such descriptions, among other questions. In order to avoid further grounds for refusal, Cult Gaia “must respond to the [additional] questions and/or requests for documentation to satisfy this request for information.”

With no end in sight as of now, it seems as though the duration of the fight for a registration for the Ark bag will, in fact, last longer than its reign as an “it” bag.