After building one of the “America’s most iconic jewelry brands,” David Yurman is looking to crack down on what it says is a pattern of “blatant and willful” copying by younger rival, Mejuri. According to the complaint that it filed in a New York federal court on Friday, Yurman alleges that direct-to-consumer jewelry brand – and “serial copyist” – Mejuri “has chosen to copy” a number of Yurman’s well-known offerings in an effort to “exploit” the Yurman brand and “the goodwill it has built,” and confusing consumers in the process, thereby, serving to infringe Yurman’s well-established trade dress rights and damage its reputation as a purveyor of “exceptional quality” products.

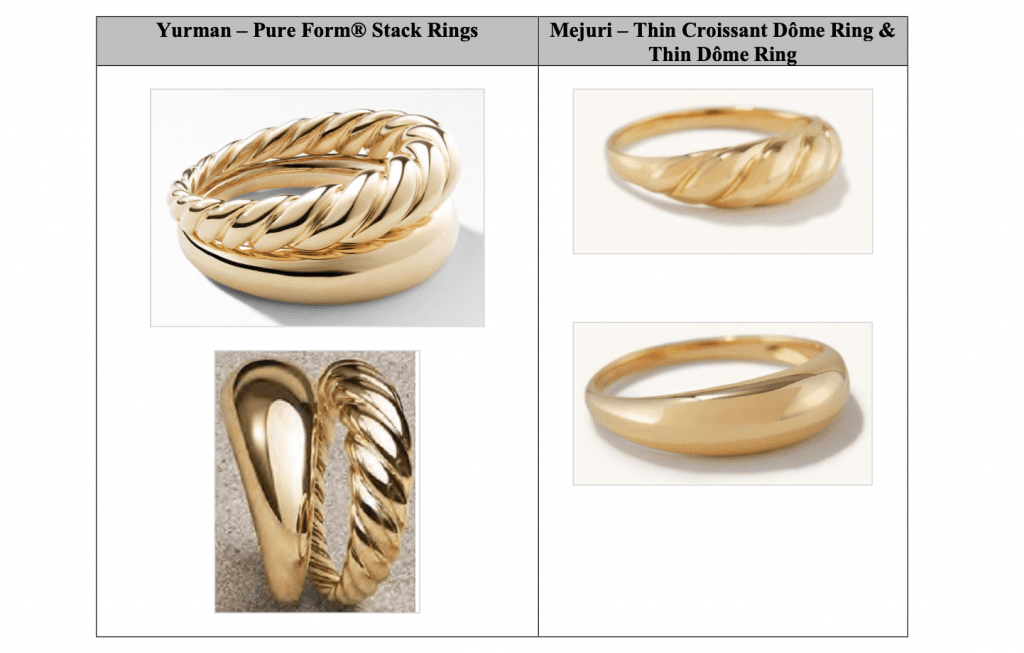

In the newly-filed complaint, New York-headquartered David Yurman sets the stage by asserting over the course of more than 40 years, its effort to “design, advertise, and sell products drawing from its signature [twisted helix cable] motif have earned intellectual property rights, including trade dress protection.” Specifically, Yurman points to its Pure Form® and Sculpted Cable collections as among the products with “a unique and distinctive shape and design such that it is recognized by jewelry consumers” and that “consist of a combination of numerous nonfunctional elements” that consumers have come to associate with its brand.

The Pure Form® Cable Bracelet trade dress, for instance, consists of a “sculpted cable motif in a twisted helix configuration; deep, wide diagonal ridges wrapping around the bracelet; rounded and smooth ridges; one portion slightly thickened or enlarged in diameter, with tapering on both sides of that portion; and bold, voluminous design that is a stationary, singular piece.”

Thanks to years of consistently offering its Pure Form® and Sculpted Cable jewelry (including the Pure Form® Cable Bracelet, Pure Form® Stack Rings, and Cable Classics Earrings), spending millions of dollars to advertise such products, enjoying “unsolicited local and national media coverage,” and generating tens of millions of dollars in sales from these products (sales of the Sculpted Cable collection, for example, have totaled over $200 million, per Yurman), the respective jewelry designs have achieved “a high degree of consumer recognition and secondary meaning … and as such, [are] distinctive and serve to identify Yurman as the source of jewelry embodying said trade dress” in the minds of consumers.

Against this background, David Yurman claims that Toronto-based Mejuri has taken to “freeriding” on the appeal of its Pure Form® and Sculpted Cable jewelry by offering up products that “directly copy” those products and causing confusion among consumers. Given the “striking” similarity between the two companies’ products, such as Yurman’s Pure Form® Cable Bracelet and either the Croissant Dôme Bracelet or Croissant Dôme Cuff Bracelet, Yurman claims that consumers that see the “copycat” Mejuri products “either at the point of purchase or thereafter, have been and will continue to be actually confused into thinking that the Mejuri product is related to Yurman.” Such confusion is furthered by the fact that Mejuri’s allegedly infringing goods “lack any differences that are memorable enough to dispel confusion on serial viewing,” Yurman declares.

As such, David Yurman argues that “ordinary consumers are likely to be confused as to the source, sponsorship, affiliation, or approval relating to the Mejuri products vis-à-vis [its own products].”

(Quick note: While elements of Yurman’s designs are not earth-shatteringly novel, that is not necessarily the death knell of its case. Unlike the novelty/originality pre-requisites to design patent and copyright protection, trade dress law does not have an equivalent requirement, and instead, rights are awarded based largely on whether or not consumers associate the combination of non-functional elements at issue with a single source; such secondary meaning is established by way of a number of factors, namely evidence of advertising expenditures, consumer studies linking the mark to a source, unsolicited media coverage of the product, sales success, attempts to plagiarize the mark, and length and exclusivity of the mark’s use.)

In addition to the similarity of the products, themselves, David Yurman contends that 8-year-old Mejuri has gone further to confuse consumers by “even work[ing] with the same models [as Yurman has] and mimicking Yurman’s images in advertising the copied jewelry.” And still yet, Mejuri has allegedly hijacked the messaging of the Yurman brand, which “has been at the forefront of female empowerment” from its founding in 1980 in connection with its attempt to pioneer a movement in which “women would purchase jewelry for themselves instead of traditionally receiving it as a gift.”

“Mejuri also claims to be built on female empowerment,” per David Yurman, which claims that Mejuri markets itself as making “fine jewelry for every day, for our damn selves” and thus, filling a void in “a jewelry industry that was built for men gifting women and not women celebrating themselves.”

Despite its practice of allegedly replicating the look of Yuman’s offerings (and those of others, including the “designs from brands like Boucheron and LAGOS”) and Yurman’s ad campaigns, as well as “the messaging of its founding and company ethos,” Yurman states that Mejuri does not copy it from a quality perspective. “Unfortunately for Mejuri’s customers, Mejuri is unable or unwilling to match Yurman’s product quality, selling products that quickly tarnish and are of lesser overall quality” even though it has “received ample resources that could be used to make quality products with original design work” via “substantial fundraising activity, including recently raising over $20 million from sophisticated venture capital firms including NEA, Felix Capital, and Imaginary Ventures.”

And in one more jab before setting out its causes of action, Yurman asserts that Mejuri similarly falls short on its purported ESG credentials. “Mejuri’s business practices contradict its claim to customers,” namely, its marketing of itself a “socially-responsible” company, and its claims that “[s]ince day one, it’s been our mission to engage with the jewelry industry in a way that compliments [sic] our values and those of our customers.”

With the foregoing in mind and the given the “damage to the goodwill and reputation of [its] business” that it has experienced as a result of Mejuri’s alleged infringement scheme, Yurman says that it is seeking to “put a stop to Mejuri’s illegal practices and obtain compensation for Mejuri’s violations.” Yurman sets out claims of unregistered trade dress infringement and state law dilution. In terms of its dilution claims, Yurman asserts that Mejuri’s activities were designed to “blur” and “dilute Yurman’s extremely well-known trade dress, and to create confusion and mistake and to deceive consumers into the false belief that Mejuri’s products are associated with, affiliated with, sponsored by, endorsed by, or otherwise connected to Yurman and its products.”

In addition to injunctive relief to preliminarily and permanently bar Mejuri from further infringing its trade dress rights, David Yurman is seeking damages and an order from the court requiring Mejuri “to melt down and recycle any remaining inventory of the infringing products and take down and destroy any and all advertising and promotional materials, displays, marketing materials, web pages, and all other data or things relating to the infringing products.”

In a statement on Friday, a Mejuri spokesperson told TFL, “The claims made by David Yurman are categorically false, and are fundamentally at odds with what we stand for and who we are as a brand. At Mejuri, we strive for a culture that lifts up creators, prioritizes transparency and empowers people and our community to proudly invest in themselves. We look forward to demonstrating that today’s accusations are entirely without merit, and believe that there is enough space in our industry for artists and jewelry designers to co-exist and thrive together without baseless attacks on one another.”

The case is David Yurman Enterprises LLC, et al., v. Mejuri, Inc., et al., 1:21-cv-10821 (SDNY).