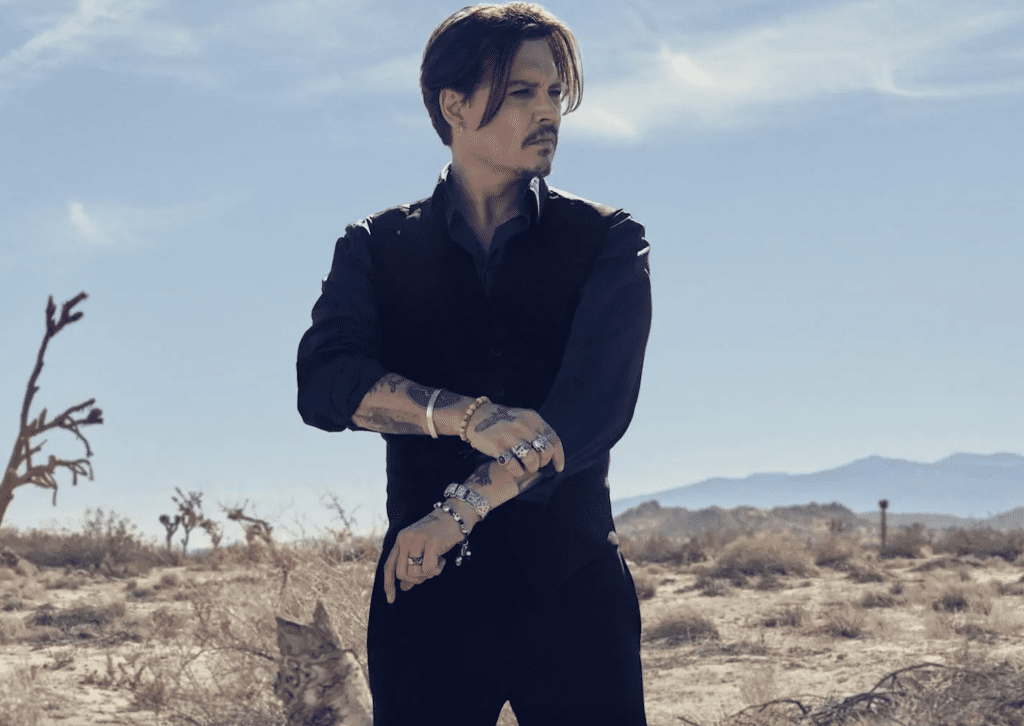

Dior found itself in a significantly problematic position in the summer of 2016. Johnny Depp was the face of Sauvage, its newest men’s fragrance at the time. The world-famous actor was starring on television screens in a commercial for the cologne, gracing billboards across the globe, and appearing in glossy magazine ads and on consumers’ Instagram timelines, alike, as part of Dior’s large-scale push to market its fragrance. All the while, Depp was making headlines for different reasons, as well, after his then-wife, Amber Heard, came forward with domestic abuse allegations against him, thereby, putting him at the center of a headline-making matter that stood to directly impact the carefully-crafted and maintained image of the fashion brand whose fragrance he was endorsing.

The scenario positioned LVMH-owned Dior – one of the most valuable and esteemed fashion houses in the world – in an inherently unflattering light, as consumers called foul and threatened to boycott the brand as a result of its choice of spokesman. The situation was striking in part because the issues at play stand to impact almost any brand with endorsers. In fact, just this week, brands have rushed to cut ties with Chinese-Canadian singer Kris Wu, who has appeared in ads for the likes of Louis Vuitton and Dior, after he was accused of sexual assault.

The issue of endorser misconduct goes far beyond any single fashion brand, and beyond the fashion industry, itself. As Jackson Walker attorneys Emilio Nicolas and Valery Piedra put it recently, “There is a seemingly trending tale in Hollywood: A film production has cast the lead role. The press release has been made. The news is trending on social media. Investments are starting to pour in. But then controversy strikes as news comes out that the lead has committed socially objectionable behavior. Things start spiraling quickly. Hashtags to boycott the film start to trend. Distributors will not agree to carry the film. Investors begin pulling funds. Now, if you are the producer, you might ask yourself, ‘How can I disassociate the film from its now controversial lead?’”

Given the rise of the #MeToo and Times Up movements, paired with the potential impact of cancel culture, brands big and small are being forced to grapple with backlash from consumers in instances in which they are tied to controversial figures.

Against this background, it is unsurprising that many companies have gone back to the drawing board – at least from a legal perspective – when it comes to enlisting Hollywood stars, professional athletes, big-name fashion designers, and heavily-followed influencers. After all, companies take on quite a significant amount of risk when contracting with famous figures to endorse or in some cases, create their products. In these situations, famous individuals and their behavior, whether that behavior comes in a professional capacity or in their paparazzi-plagued or social media-documented personal lives, often serves as a reflection of the brands these individuals are formally tied to, thereby, pulling companies into situations even when they are otherwise uninvolved.

In certain instances of endorser misconduct, it may be as simple as pulling online advertisements or no longer allocating future ad spend to the individual at issue. But often, it is more complicated than that, especially when a brand is already involved with an influencer or other famous figure. In order to protect themselves and their carefully crafted identities, brands are doubling-down on the terms that appear in their contracts with ambassadors, endorsers, designers and/or other figures, and using morals clauses with more frequency than maybe ever before.

A Legal Conundrum

Morals clauses refer to contractual provisions that serve to prohibit or otherwise dictate certain behavior of an individual or party to a contract, and are typically worded in a way that enables a brand to immediately terminate a contract, without any penalty, should the other party behave in a manner that would tarnish its reputation. Beyond permitting a company to back out of an existing deal, these contract provisions also tend to allow the brand at issue to seek any number of potential remedies for its star’s violation, including but not limited to: the termination of the agreement; suspension the agreement for a period of time; imposition of a financial penalty for the behavior at issue without terminating the contract; or the payment of damages by the famous figure for breaching the agreement.

“Endorsers naturally want the clauses to be as narrow and specific as possible. For example, a clause might only kick in if an endorser is convicted of, or pleads guilty to, a felony,” according to Kelley Drye’s Gonzalo Mon. “This type of clause will not necessarily help if a celebrity is only accused of sexual misconduct,” he says, noting that companies want more flexibility. For example, they may push for a clause that allows termination if the endorser’s actions would subject the company to ridicule, contempt, controversy, embarrassment, or scandal.

With the foregoing in mind, “The effectiveness of your clause depends not only on its scope, but also on how it works in conjunction with other provisions in your agreement,” Mon says. “Consider, for example, how things work if your payments are stacked towards the front of the term. You may be able to terminate for a breach later in the term, but you may not be able to recoup the money you’ve already invested.” He further notes that “there is not a one-size-fits-all approach here, [and] a lot depends on the person with whom you are negotiating, the amount of money involved, and the nature and length of the campaign.”

Companies are also encouraged to look beyond the terms of the agreement, itself, and consider the expanding pool of individuals that such clauses apply to. While morality clauses are most commonly discussed when a company is signing a famous face to their brand, whether it be an actor, athlete, influencer, or even a creative director, Nicolas and Piedra note that these legal tools may also be applicable in “business situations where the act of one party can reflect negatively on the other,” and thus, may extend beyond traditional endorser figures.

As such, their inclusion “can be invaluable should a party become embroiled in a scandal that indirectly harms a company or a project’s success by association,” they state, encouraging companies to “give some thought to the inclusion of a morality clause the next time you find yourself negotiating a contract with talent” or any other public-facing individual, who might serve to represent the brand, including top level managers and C-level figures.

*This article was initially published in January 2018 and has been updated.