From Crocs giving away hundreds of thousands of its plastic clogs to medical professionals and buzzy beauty startup Glossier offering up its brand-new land lotion product to doctors, nurses, and other healthcare staffers to BHLDN, Anthropologie’s bridal brand, giving away wedding dresses to essential workers who are also brides-to-be, the onset of the COVID-19 health pandemic has prompted no shortage of companies to look to giveaways and large-scale donation initiatives to meet the needs of those on the frontlines, and to build some goodwill around their brands in the process.

Hardly a novel tactic, consumer goods brands often use giveaways as a marketing tool to garner buzz among the consuming public. When they execute these opportunities appropriately, businesses can see sizable spikes in revenue and consumer loyalty as a result. At the same time, when a giveaway campaign is poorly structured, and ultimately goes wrong, brands can suffer from at-times-irreversible reputational harm.

Look no further than Reese Witherspoon and her fashion brand Draper James, which recently provided an example of what a giveaway gone wrong looks like.

“In mid-March, just around the time that American schools and offices started closing because of the coronavirus pandemic, not that long before numerous designers had suddenly become heroes for volunteering their services to hand-sew masks so that surgical-grade ones could go to those who needed them most, the staff at Draper James started talking about doing something for teachers,” the New York Times’ Vanessa Friedman wrote last month in the wake of what would prove to be a public relations nightmare.

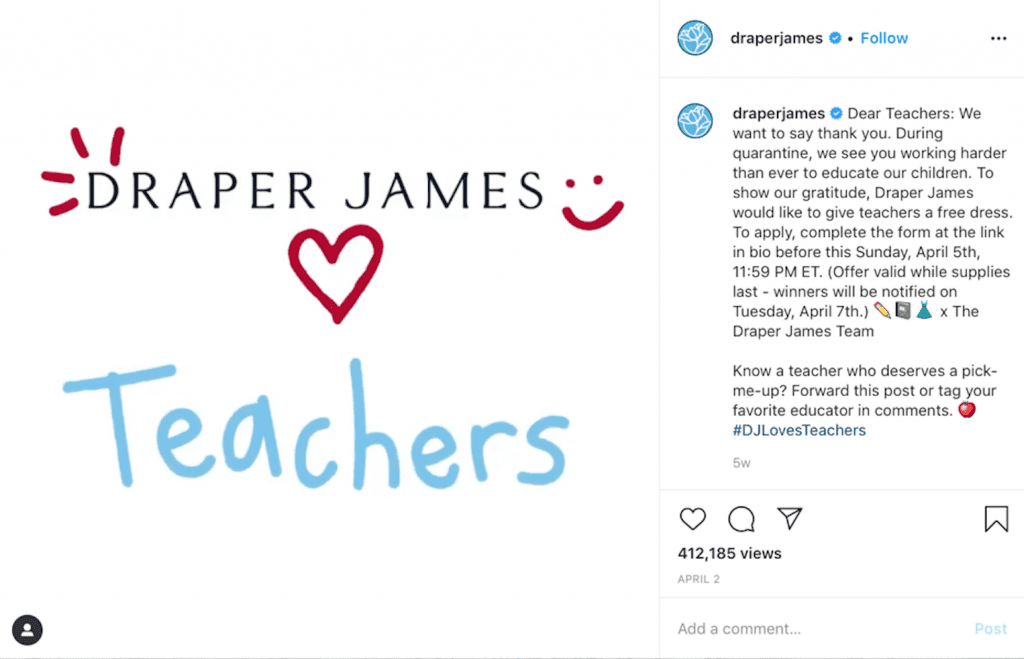

Draper James’ staff landed on a giveaway. The 7-year old fashion and lifestyle brand would provide teachers across the U.S. with dresses from its collection. So, the team took to Instagram on April 2 to announce the new initiative, writing: “Dear Teachers: We want to say thank you. During quarantine, we see you working harder than ever to educate our children. To show our gratitude, Draper James would like to give teachers a free dress.”

The Instagram post went on to explain the details, namely, in order to be eligible, teachers would need to complete a form to “apply,” and provide Draper James with information, including their names and email addresses, in order to have a chance to “win.” It also alerted them to the fact that the offer was only “valid while supplies last.” As hordes of outraged teachers would soon learn (Draper James received more than one million entries, prompting its website to crash shortly after the giveaway was announced), the supply of dresses was not in the hundreds of thousands. It was much less than that.

“Draper James, a company that is only five years old and has fewer than 30 employees, had only 250 dresses, in six different styles, to give away,” Friedman reported, noting, at the same time, that “while it is true that the company is small, Ms. Witherspoon herself is big, maybe even one of the most powerful people in Hollywood.”

The once-exciting giveaway swiftly turned into a social media disaster, with Instagram users angry about the “misleading” giveaway and the brand’s “poor communication.” Others expressed concern about what they saw as a “deliberate stunt designed to capture [entrants’] email addresses.”

In an attempt to undo some of the PR damage, Draper James revealed that it would make a donation to an education-specific organization, and would provide every person that entered to win a dress with a Draper James discount code.

As for whether consumers will hold the brand to the poorly-executed giveaway – which has since been referred to as “Celebrity #Covidwashing,” a new term that likens COVID-19-specific marketing to greenwashing, or marketing that dupes consumers by providing false or misleading information about how sustainable or environmentally-sound a company and/or its products are – is yet to be seen. One thing that is immediately clear, though, is that brands need to be hyper-vigilant when it comes to their initiatives in order to avoid public outrage.

Specifically, David Klein, a managing partner at Klein Moynihan Turco, who specializes in internet marketing and sweepstakes, says that brands “need to use clear language to explain when a promotion is, in fact, a [limited] sweepstakes versus a giveaway with prizes provided to allwho sign up.”

That distinction is only important when a brand is aiming to avoid allegations of #Covidwashing, but is significant from a legal perspective, as sweepstakes and giveaways are legally distinct things, and must be treated accordingly, as “sweepstakes and contests require brands to comply with state and federal laws in order to avoid fines, reputational harm and, potentially, criminal sanctions,” according to Klein.

As for what was going on in the Draper James scenario, by most accounts it was a “sweepstakes” – the legal term of art that is used synonymously with “giveaway” – because it was a promotion where something was given away for free; the brand was giving away free dresses.

But the situation might actually be a bit more complicated when such sweepstakes ask for something in return from those entering for a chance to win the free thing(s), such as one of the 250 dresses. Requiring that the potential entrants provide something of value in exchange for a chance to enter (and maybe win) changes the scenario pretty significantly: it makes the sweepstakesa lottery, and it is illegal for private entities (i.e., non-state government entities) to hold lotteries.

So, what exactly is a lottery? It is a promotion that consists of three main elements: chance (i.e., the winner(s) is chosen at random and no skill is required); a prize; and consideration (i.e., something of value provided by the entrant). The last element is the tricky one because consideration is broader than merely paying for a chance to enter. It extends to purchasing a product, for example, or investing substantial time into completing an entry application.

The question in this hypothetical Draper James case and many others just like it is whether providing the company with personal information – here, teachers had to provide Draper James with their name, email address, and a photo of their school ID, among other things – in exchange for a chance to win constitutes consideration.

“The question of whether requiring consumers to provide personal information or to agree to receive commercial email or other content as a condition of entry constitutes consideration has been a topic of conversation in legal circles for years,” according to Marc Roth, a partner at Cobalt Law LLP, who specializes in advertising and marketing compliance. “Yet, we are yet to see a viable challenge in this area for several reasons,” one of which is the fact that in the U.S., “personal contact information is viewed as having little to no economic value, and as a result, would likely fail to constitute consideration in a lottery analysis.”

As for how we know that consumer information is generally not considered to be a marketable asset, Roth says that the treatment of such information in connection with data breach lawsuits, in which affected consumers seek damages for the unauthorized access to or release of their personal information, is telling.

“Although almost every U.S. state has a data breach law, none of them provide a private right of action with statutory damages for affected consumers.” Even if consumers look beyond data breach-specific laws, such as to tort causes of action, Roth says that “courts have universally rejected claims where the only harm claimed is the data holder’s failure to protect the breached information. In these cases, courts have not found consumer contact information alone to have monetary value worthy of granting equitable relief to consumers.”

The outcome of this analysis “may be different,” per Roth, “when the breach involves sensitive data, such as health or financial information,” and if such a case were initiated outside of the U.S., such as in the European Union, “where the right to one’s privacy in their personal information is a fundamental human right, and violations of privacy laws carry statute-mandated financial penalties.”

Since the data at play in the Draper James dress scenario is limited to contact information, and was presumably open only to consumers in the U.S., since the brand only ships domestically, neither of those considerations apply.

Even if Draper James has not seemingly run afoul of the law by way of its dress giveaway, the brand – and others looking to boost morale and marketing by way of similar endeavors – should pay close attention to how their most well-meaning promotions are likely to be interpreted by the average consumer in order to avoid sweeping backlash as in the case at hand.

“On its face, Draper James looks to have had good intentions,” Klein states. Yet, because “consumers rarely read promotional details” and since the brand said it was ‘giving away’ dresses, instead of ‘offering consumers the chance to win,’ Draper James received considerable consumer backlash that could have been avoided.”