In every order that a consumer makes on Glossier’s e-commerce site or in its small network of brick-and-mortar outposts, the products – whether it be the Generation G blotted lipstick, the cult-favored Boy Brow eyebrow product, or the brand’s Balm Dotcom and Cloud Paint multi-purpose skin salves, etc. – come packaged in a ziplock pouch. Millennial pink, of course, the pouches are unique in that they are composed almost entirely of bubble wrap.

In furtherance of Glossier’s quest to become “the Estee Lauder of the future,” as founder Emily Weiss put it, the New York-based direct-to-consumer brand has raised nearly $200 million in venture funding, “making it one of the most well-funded privately held beauty businesses,” per TechCrunch, and has been busy building out an arsenal of products and trademark rights, alike, filing applications for registration for its signature pink hue as applied to bubble wrap bags, among other things, such as its brand moniker and various product names, as well as the shape of its “Play” fragrance bottle and its millennial pink-lined shipping boxes.

On the heels of filing a trademark application for its pink bubble wrap-lined ziplock pouches – which it uses in connection with its marketing and sale of “cosmetics; makeup; [and] skincare products” – in the spring of 2019, the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (“USPTO”) pushed back.

In an initial (and non-final) refusal to register the Glossier pink pouch trademark (or better yet, pink pouch trade dress) in July, an examining attorney for the trademark body held that the pink pouch is ineligible for registration because it “appears to be a functional design for such packaging” (and functionality is an absolute bar to registration), and because the mark “consists of a nondistinctive configuration of packaging for the goods that is not registrable … without sufficient proof of acquired distinctiveness.”

In terms of the latter, the USPTO essentially claimed that the ziplock pouch is – on its face – incapable of identifying the source of the products at play (at least in part because bubble wrap lining a common feature of “goods that are going to be in transit or are going to be shipped,” and Glossier’s use of “the color pink … on such pouches is not unique”). The USPTO’s claim that the pouch does not serve to identify a single source is significant since the purpose of a trademark law is to identify and distinguish the goods of one company from those of others, which means that in order to function as a trademark, a name, logo, color, product package design, etc. must be able to identify the source of the goods/services that it is used in connection with, i.e., a single source.

As such, in order to benefit from a registration, Glossier must show – by way of a handful of factors, such as unsolicited media attention, advertising expenditures, sales success, etc. – that consumers have come to link the pink pouch with the Glossier brand. And that is precisely what Glossier set out to do in its response to the USPTO’s preliminary refusal.

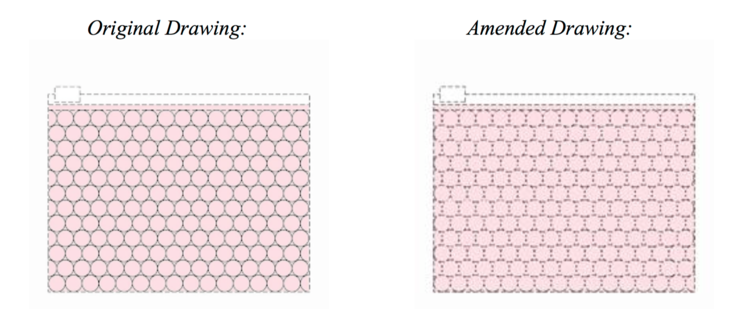

By way of a new 252-page filing this month, Glossier initially clarifies exactly what the mark at issue is: “the mark consists of the claimed color pink as applied to a very particular type and configuration of product packaging,” asserting that “the air bubbles and the packaging itself are not claimed as features of the mark.” By disclaiming any rights in the packaging, itself, and only claiming rights in the specific color pink when used on such packaging, Glossier claims that it removes any issues involving functionality.

As for the bulk of Glossier’s filing, that centers on the brand’s assertion that its use of the color pink on its packaging has acquired distinctiveness, namely “based on five years’ use of the mark, as well as extensive evidence that when the relevant consumers see the color pink on a bubble-lined, zip-top pouch, they immediately recognize it as Glossier’s Pink Pouch.”

To prove that, Glossier provides third-party media articles about its brand that make mention of its use of the pink pouch, as well as examples of consumer social media posts featuring the pink pouch, which Glossier says “demonstrate that many consumers already associate the Pink Pouch with [it], [while also] serving to educate even more consumers and reinforce the association between the Pink Pouch and Glossier.”

The brand goes on to assert that the pink pouch “has been used continuously since at least as early as 2014 [by Glossier], and in 2018, the revenue generated by sales of goods [that included use of] the mark amounted to more than $100 million.”

While the company states that it “has consistently promoted the Pink Pouch by featuring it on the Glossier website, in numerous marketing emails, in social media posts, and even on New York City subway ads,” it does not mention how much it has spent on advertising, which is typically a relevant consideration in connection with an acquired distinctiveness inquiry. It does, however, reveal that “in 2018, more than 1,000,000 new customers purchased goods sold [using] the mark.”

Still yet, an additional factor that is considered when determining acquired distinctiveness is the “evidence of parodies and copies,” which Glossier states “may also be considered in assessing whether the mark has successfully achieved public recognition as a source indicator.” In the case at hand, Glossier points to “a pink handbag with a texture mimicking bubble wrap” that Jimmy Choo released in 2016, which the beauty brand claims was “suspected [by] many in the industry” as meaning “to copy Glossier’s Pink Pouch.”

With such an “abundance of evidence” in mind, Glossier asserts that “the color pink, as applied to bags featuring lining of translucent circular air bubbles and a zipper closure, has acquired source- indicating significance in the minds of the relevant consumers.” In other words, “when consumers see the Pink Pouch, they immediately recognize it as emanating from Glossier,” and thus, the mark should be registered.

It is now up to the USPTO to determine whether Glossier has overcome its preliminary points of refusal and thus, give the go-ahead to the application to move forward with the pre-registration process or whether it will issue another non-final rejection.

Glossier’s quest to earn a trademark registration for its use of the color pink on specific product packaging comes as a growing number of brands are placing increased emphasis on slightly less traditional trademarks (i.e., those other than just brand names and logos). Maybe most noteworthy is red-hot streetwear brand Off-White, which has been making use of less conventional elements, such as quotation marks and zip ties, on its products in order to indicate the source of those products. All the while, it is aiming to amass trademark rights in those marks, and policing others’ unauthorized uses of them.

This comes as part of a larger trend in trademarks. As trademark research and protection consultancy CompuMark noted in a recent report, such expansive approaches to trademarks, including the addition of industrial design and image marks to their filing strategies, might be a result of the fact that “finding a unique mark is a challenge” in the crowded, modern market. This is a noteworthy concern for brands, especially in light of research showing that the supply of available trademarks is “severely depleted, particularly in certain sectors of the economy,” such as fashion and retail, more generally.

With that in mind, brands are not only adopting interesting names and logos – whether they are dropping letters from existing words, simply adopting monikers that consist of just a few letters, adding numbers to their names, or in some cases, relying exclusively on numbers – in order to differentiate themselves from competitors (and acquire trademark rights and the increasingly hard-to-come-by domain names and social media handles for their brands). They are also looking to additional elements, whether it be like product packaging or designs like zip ties, for help setting themselves apart in the minds (and wallets) of consumers, as well.

Moreover, in an inherently digital age, one in which Instagram often serves as the main platform for product discovery and the home of large-scale advertising efforts for many brands, this focus on additional, highly visual trademark elements makes a lot of sense.