Deep Dives

Much has been made as of late about consumers’ concerns about the impact of their purchases on the environment and the individuals that comprise companies’ often far-reaching and overly-opaque supply chains. Yet, despite widespread reports about Gen Z and millennial demographics, in particular, prioritizing sustainability when it comes to their buying habits, and thereby, prompting many brands to adopt ESG-focus marketing efforts and everything from recycling initiatives to sustainability-centric capsule collections, analysts say that there is relatively little evidence to show that consumers’ interest in sustainability generally actually translates to a change in their consumption habits.

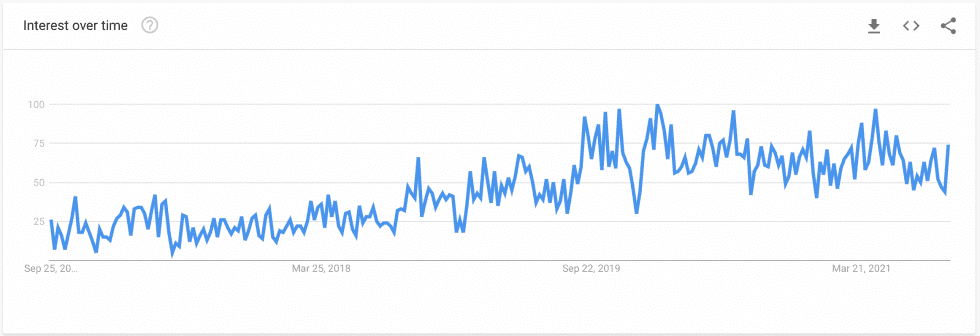

While consumers may be voicing concerns about sustainability and ESG (and doing their ressearch, based on Google search trends), they “do not necessarily act on those concerns,” Jelena Sokolova, senior equity analyst at Morningstar, recently told CNBC. Many consumers are “not necessarily buying more sustainable products,” she says, also noting that “we do not have the indications that people in the Western world are consuming less clothing that they were ten years ago.” Gains for fast fashion brands in terms of revenue in recent years and recent quarters, alike, seem to further establish the enduring pattern of consumers continuing to purchase apparel en mass.

Rising consumer searches for “sustainable fashion”

Zara owner Inditex, for instance, reported this month that Q2 revenue and profits reached “historic highs,” with its 6.99 billion euros ($820 billion) in sales for the 3-month period ending on July 31 easily beating pre-pandemic levels. The stunning rise of Chinese fast fashion behemoth Shein, whose key demographic is Western millennials, should also be telling. Add to this the fact that “consumers are generally not willing to pay more for sustainable products,” which is likely deterring a large portion of consumers, and which means that if companies want to clean up their supply chains or cut emissions, for instance, they “will probably have to take these costs to their bottom line, share them with suppliers, or off-set them with other efficiencies,” Sokolova asserts.

The fact that many consumers are not really acting on their sustainability concerns in any large-scale way (with the potential major exception here being the rise of the $40 billion resale market) does not mean that brands should not be making efforts on the ESG front because investors appear to be acting on such budding consumer concerns. As I noted in last week’s newsletter,investors are paying attention to the rising potential for actual pushback against the disposable fashion model. In an article this past week, the Wall Street Journal’s Carol Ryan noted that despite Inditex making a full recovery from COVID and the company being in “better shape” than pre-pandemic, its share price is still down.

Ryan posited that at least some of the value-shrink may be due to “investors see[ing] new risks for sellers of cheap clothing.”

At the same time, in an effort to cater to increased investor interest in companies’ ESG metrics, Fitch Ratings recently announced the launch of new ESG ratings system, while Mintz’s Jacob Hupart notes that both of the other major ratings agencies – Moody’s and S&P – have also launched products focusing on decoding ESG issues for investors.

Beyond investors placing value in – or subtracting it from – companies (and their share prices) based on ESG elements, publicly-traded companies should also be paying attention because the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (“SEC”), and Chairman Gary Gensler, are. The regulator, “under the Biden administration and with its new chairman, is expected to be more aggressive in pursuing enforcement actions against companies and their directors and officers than the previous administration,” Jenner & Block LLP partner Howard Suskin said recently.

Still yet, the risk of litigation for companies, as well as their directors and officers, continues to reveal itself by way of legal battles that center on alleged misrepresentations relating to companies’ ESG initiatives. To date, lawsuits in this realm have included consumer protection, breach of warranty, fraud, and unjust enrichment claims (as indicated by the lawsuit filed against Canada Goose and another waged against Allbirds, for example), and have taken the form of shareholder derivative actions alleging that companies and their officers have failed to live up to their publicized ESG aspirations. Suskin states that these lawsuits “can also take the form of shareholder class actions, if disclosure of a material risk of an ESG issue causes the company’s stock price to decline, giving shareholders the opening to argue that the disclosure should have been made sooner.”

The potential for shareholder litigation seems likely to only increase further, as companies, like Allbirds, for instance, make strides towards going public, and place notable significance on their eco-friendly operations as a way to differential themselves in the market, thereby, opening themselves up to such potential shareholder lawsuits. (To put Allbirds’ emphasis on sustainability into perspective, it mentioned “ESG” Almost 100 times in the nearly 60-page S-1 that it filed with the SEC last month; it mentions “carbon” 114 times, “sustainability” 112 times, “climate” 51 times, and “green” 45 times.)

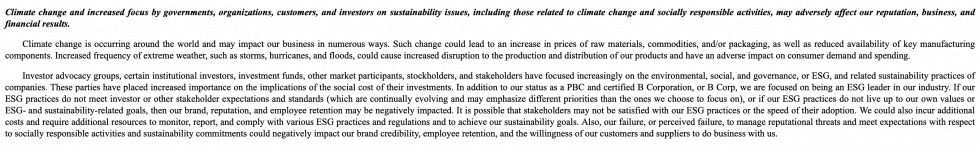

Simultaneously, Allbirds cites rising attention to ESG as a risk factor in the same filing.

In addition to the sheer risk of reputational damage that comes hand-in-hand with such suits, Suskin notes that “defending these actions has become somewhat more difficult in the wake of the Supreme Court’s June 2021 decision in the Arkansas Teacher Retirement System’s securities fraud case against Goldman Sachs Group, where the court allowed for the possibility that generic statements by the company about its integrity and customer practices could have artificially inflated the company’s stock price.” He says that “even if ESG-related cases do not survive a motion to dismiss (and many of them should not, because the statements complained about are often aspirational and are not alleged misrepresentations of historical fact),” companies that are forced to defend such cases “usually incur significant legal defense costs.”

Against this background and in light of investor pressure increasing the importance of attention to environmental and social elements for a wide array of consumer-facing businesses, ESG issues are swiftly rising in the ranks of more traditional risks that businesses and their boards are forced to grapple with. Ultimately, if the growing number of lawsuits demonstrates anything, it is that companies need to meticulously balance their ongoing efforts to attract consumers by way of ventures in the ESG space with a consistent and careful review of all ESG-centric statements, even seemingly vague and/or forward-looking ones, and supplement them with any necessary disclosure language.

And from a consumer perspective, companies should view such burgeoning attention as an impetus to mitigate missteps in connection with their attempts to bolster their sustainability credentials. While consumers may not be acting on their eco-centric concerns (yet), they very well may not be immune to participating in the enduring cancel culture should a brand become embroiled in a greenwashing or other ESG-related scandal.