Deep Dives

“In the past year, we have digitized Fashion Week, made strides to make less and produce it more sustainably, and cut back on global fashion travel,” Vogue’s Stef Yotka wrote in a recent piece reflecting on the past “year of change” as the fashion industry has coped with the impact of COVID-19. It seems that on many fronts, fashion – and other industries – have achieved heightened awareness about the need to prioritize sustainability, particularly as a result of the global health pandemic and amid growing consumer attention to the manufacturing and the post-initial-sale lifecycle of the garments, accessories, and even the beauty products that we buy.

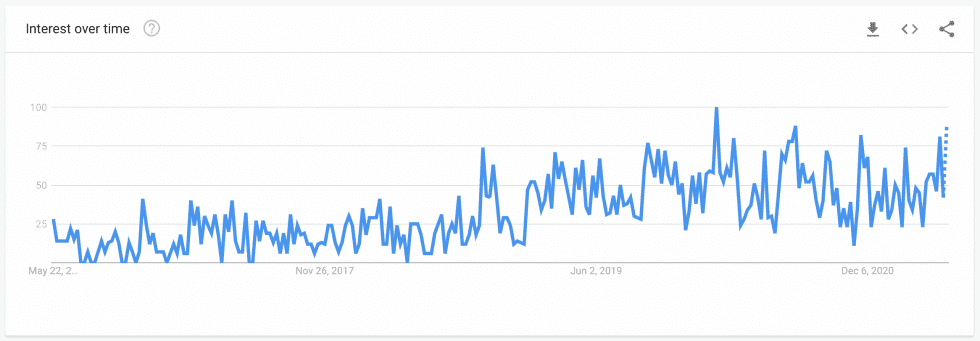

As consumers continue to demonstrate their interest in sustainability (as indicated by rising Google searches for things like “sustainable fashion” and “ESG”), some brands appear to actually be making less. “Designer Dries Van Noten has significantly scaled down his men’s and women’s collections,” according to Vogue. “We got rid of all the clutter, let’s say, because we had felt that we had to make a lot of things just to make them,” says the designer, estimating his menswear collection has decreased in size by 40 to 45%, and his womenswear by 35 to 40%.

At the same time, Giorgio Armani said that his eponymous label is also scaling back with the aim of reducing the size of its collections by almost one third. “A large percentage of the global fashion output ends up unsold and discarded to the black market or outlets,” he told WWD. “I don’t want to work for the outlets, that is for sure: that would hugely diminish, if not dismiss, the value of what I do.” As a result, Mr. Armani says that he is “reducing the number of variations on certain looks, making the offer sharper and more focused.”

Google searches for “sustainable fashion” from May 22, 2016 to date

Google searches for “sustainable fashion” from May 22, 2016 to date

While some brands are expected to follow suit and scale back, others will inevitably take a different route. After all, companies in the mass-market segment and at the upper-end of the spectrum rely on high-volume turnover to generate billions in revenue, and thus, are on a consistent quest for growth. Maxine Bédat, the Executive Director at New Standard Institute, recently pointed to a sponsored article run (and since removed) by the Guardian, in which H&M CEO Karl-Johan Persson argued that “decreas[ing] 10 to 20% of everything we do not need” could have a “catastrophic effect on the social and economic side.”

In lieu of cutting back, he said that H&M aims to operate “in a way where you still can have economic growth and jobs creation, while finding the innovations that can limit the damage to the environment.” These initiatives range from sustainable cotton sourcing to a “fair living wage” strategy.

Persson’s sentiments and the contents of a growing number of major apparel and retail entities’ Environmental, Social, and Corporate Governance (“ESG”)-centric reports seem to suggest that constant growth can be achieved responsibly – or in other words, that sustainability and scale can co-exist. While there is clearly a clash in positions about whether this is realistic, and about what the best way forward looks like, particularly when the quest for unencumbered growth is involved, one thing that is not up for debate is that there is an enduring rise in consumer and investor interest in sustainability and ESG, which has permeated brands’ marketing activities.

As such, the question of whether sustainability and scale can co-exist is joined by another pressing one: can brands pursue growth, market things like “green” targets, and remain on the right side of the law?

To date, fashion brands have largely managed to appease consumers and investors with proclamations about their “eco” efforts, and skirt legal ramifications for questionable claims. (Although, many have faced accusations of greenwashing). However, the status quo may be subject to change, even in instances when the sustainability marketing is vague and aspirational in nature. One need not look further than the messages being sent by the Securities and Exchange Commission (“SEC”) – and the frequency of those messages – to see that developments are afoot.

Between February 24 and April 12, the securities regulator posted five public statements and two press releases on its website – all of which focus primarily on ESG. Among them: an announcement about the creation of a Climate and ESG Task Force in order to “develop initiatives to proactively identify ESG-related misconduct,” and another about a potential plan to adopt “mandatory, rather than voluntary, standards” for reporting ESG disclosures.

The SEC also announced in April, as first reported by the WSJ, that it had discovered that a number of unnamed investment institutions “were making potentially misleading statements about their ESG investment processes, as well as their adherence to global ESG frameworks.” In plain terms, the SEC appears to be making good on its vow to crack down on companies that are saying one thing about their efforts when it comes to ESG issues, including climate change and corporate diversity, and doing another. This could – and very well might – have a trickle-down effect for the fashion industry and retail more generally, which has faced consistent claims of greenwashing (i.e., the misstating or overstating of sustainability efforts) for years and has long-maintained a presence on lists that identify industries responsible for contributing high levels of greenhouse gases.

Beyond SEC announcements, it is significant that companies’ generalized, often noncommittal ESG statements are starting to come under the microscope in a litigation context. As we dove into here, there is mounting talk about how seemingly unobjectionable statements about circular business models, pushes for diversity and inclusion, and quests to cut down on carbon emissions may become actionable if companies’ stock prices drop as a result of specific ESG issues. As Bracewell LLP’s Keith Blackman, Joshua Klein, Rachel Goldman and Russell Gallaro previously noted, at least “a few companies have already been the target of lawsuits claiming that [they] failed to live up to aspirational statements,” such as “we are committed to sustainability” or “achieving net-zero carbon emissions is our top priority.”

Taken together, the swiftly shifting nature of this space means that companies need to keep a close eye on their ESG disclosures (and how they compare to their actual practices), as what has worked in the past may no longer cut it – from a regulatory standpoint – in the future.

The Broad View: With consumer and investor pressure in the ESG sphere continuing to mount, companies are adopting sustainability-centric marketing, and in many cases, they are making ESG disclosures in their formal SEC reporting and/or putting them at the heart of supplementary disclosures on their websites and in investor reports. The traditional lack of regulation in the ESG realm may make it tempting for brands to bolster their bottom lines by playing into such rising interest in sustainability and making oversized marketing efforts and/or more-ambitious-than-objective “eco-friendly” statements.

However, just as the focus on if/how scale and sustainability can co-exist is an important one for fashion entities to consider, the potential for misalignment between ESG-related statements and actual practice should be a consistent point of attention for brands, as it appears to be an increasingly important issue for regulators.