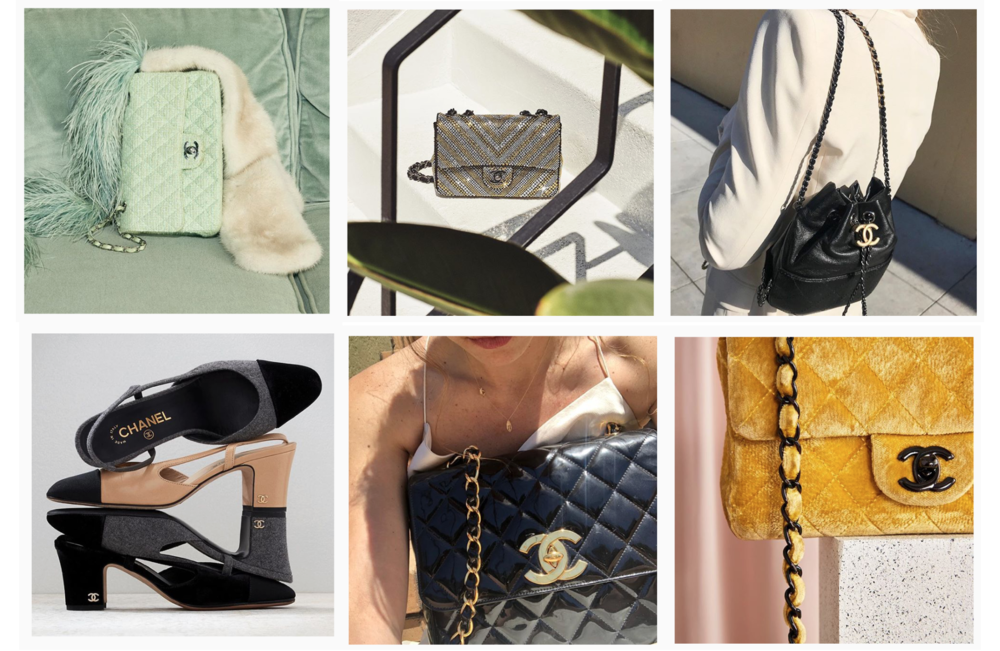

In November 2018, Chanel sued The RealReal. The 111-year old Paris-based couture house claimed that the barely 10-year old luxury resale site had built a business by running afoul of the law. To be exact, Chanel accused the burgeoning resale startup of “selling counterfeit Chanel handbags,” and asserted that “through its business advertising and marketing practices, [The RealReal] has attempted to deceive consumers into falsely believing that [it] has some kind of approval from or an association or affiliation with Chanel” when it does not, “or that all Chanel-branded goods sold by The RealReal are authentic.”

On the heels Chanel’s highly-publicized filing, The RealReal argued in its formal response that the basis for Chanel’s lawsuit – which centers on the alleged sale of “at least 7” fake bags by The RealReal – “is not [the brand’s] concern with public injury,” which is what Chanel claimed in its complaint. Instead, the resale site claims that it is the luxury brand’s attempt to stifle “lawful competition from its customers’ sale of their used goods at lower prices in the secondary market.” In other words, as a representative for The RealReal told TFL, Chanel’s lawsuit “is nothing more than a thinly-veiled effort to stop consumers from reselling their authentic used goods, and to prevent customers from buying those goods at discounted prices.”

The striking allegations by Chanel and the impassioned consumer-centric response by The RealReal have not only made for a headline-making legal battle (which is still underway), but they also speak to the tensions that exist in the $25 billon-and-growing luxury resale ecosystem as a result of how significantly digitally-native companies, such as The RealReal and Vestiaire, and the many third-party marketplaces, i.e., Amazon and Poshmark, have disrupted the ability that brands once had to control – almost entirely – how and where their products were sold, and at what prices.

Putting aside (for now) the questions that are specific to the Chanel v. The RealReal case, including the authenticity of the trademark-protected double “C” logo-bearing bags at issue, there is a more foundational point worth considering: what is the legality of the resale model in the first place? Is it legally above-board for sites like The RealReal – or eBay before them – to offer up the trademark-bearing products of another company without that company’s authorization?

The short answer to that question is … generally yes, and that is because of the existence of a trademark tenet called the first sale doctrine.

The first sale doctrine – or the doctrine of exhaustion as it is known in international jurisdictions – holds that once a trademark owner (i.e., the entity with rights in any word, name, symbol, device, or any combination used or intended to be used to identify and distinguish the goods/services of one seller from those of others) releases one of its products into the market for the first time, its right to control the distribution of that product is exhausted. This means that, for the most part (and subject to some exceptions), it cannot prevent the subsequent re-sale of that product by its purchaser.

The RealReal alluded to this doctrine in its response to the Chanel case, asserting that the lawsuit, itself, stands in direct opposition to “settled law and consumer rights,” particularly in light of the (alleged) fact that there is no likelihood that consumers would be confused as to whether there is an affiliation between The RealReal and Chanel and/or whether Chanel had otherwise endorsed the reseller’s offering and sale of pre-owned Chanel products. (The RealReal bolstered this trademark infringement-focused argument by pointing to an express disclaimer on its website that explicitly states that it does not maintain any affiliation with the brands whose products are available.)

The San Francisco-based resale company also asserted that it is not using Chanel’s trademarks “too prominently or too often, in terms of size, emphasis, or repetition.” Instead, it uses brands’ trademark-protected names and logos only to the extent that it is necessary, such as to identify or describe the products it sells, which it argued, is protected by fair use (nominative fair use to be specific).

On its face, the first sale doctrine appears to neatly shield resellers of authentic goods from liability, but unsurprisingly, it is not always as straightforward as that, as the doctrine comes with some notable exceptions.

For one thing, the first sale doctrine does not protect alleged infringers that sell trademark-protected goods that are “materially different” than those sold by the trademark owner or its authorized dealers. “This is the case at least where there is a difference in the product, packaging, contents or warranties,” the American Bar Association states.

As for what constitutes a “material difference,” that could be “virtually any physical or non-physical difference (however subtle) that exists between the authorized goods and unauthorized goods that a consumer would likely consider [to be] relevant when purchasing the product.” In terms of non-physical differences, Ohio-headquartered firm Vorys notes that “courts have recognized that certain benefits accompanying the authorized sale of a genuine product can constitute material differences,” such as when the initial customers of a product “get additional associated benefits – like a warranty, money-back guarantee or access to promotions.”

In instances like that, the subsequent resale without such additional perks could be deemed “materially different” even if the physical product, itself, is the same.

More than that, another exception states that the first sale doctrine does not apply when the trademark holder can show that it has established quality control procedures that are “legitimate and substantial;” that it abides by its quality control procedures; and that the unauthorized seller is not abiding by those procedures, making it so that its unauthorized sale of the products is likely to cause harm to the value of the trademark and create a likelihood of consumer confusion.

Beyond the “material differences” exception, there is another potential snag for those looking to claim protection by way of the first sale doctrine, one that was addressed in a separate but related lawsuit that Chanel filed in 2018 against vintage reseller, What Goes Around Comes Around (“WGACA”). In response to Chanel’s case, WGACA claimed first sale protection, but in an October 2018 decision, Judge Louis L. Stanton of the Southern District of New York essentially said, “Not so fast.”

According to the court, the first sale doctrine does “not give WGACA protection” because it “applies only where a ‘purchaser resells a trademarked article [bearing] the producer’s trademark, and nothing more.’” In that case, the court held that WGACA is not the immediate purchaser of the Chanel goods – that would be the individual who went into the Chanel store and bought the bag(s) – but instead, a re-seller of them. (That case is still underway.)

Even with such exceptions in mind, the first sale doctrine provides that one who purchases a branded item generally has a right to resell that item in an unchanged state; however, the rise of resale sites and marketplaces like Amazon has created some interesting questions about its application. It will be interesting to see how far plaintiffs like Chanel and defendants like The RealReal (and ultimately, certainly Amazon) are willing to litigate the issues at hand and to what extent – if any – public policy will play.

As Yvette Joy Liebesman and Benjamin Wilson argue in The Mark of a Resold Good, an interesting and still particularly relevant article from 2012, “Policies that advance a trademark owner’s ability to control all distribution channels would harm consumers and disincentivize competition; manufacturers would have less motivation to innovate and improve their product when they control all distribution of goods beyond their first sale. Conversely, protecting the resale market increases consumer choice and spurs mark owners to innovate and develop new and improved products.”

*This article was initially published in February 2019.