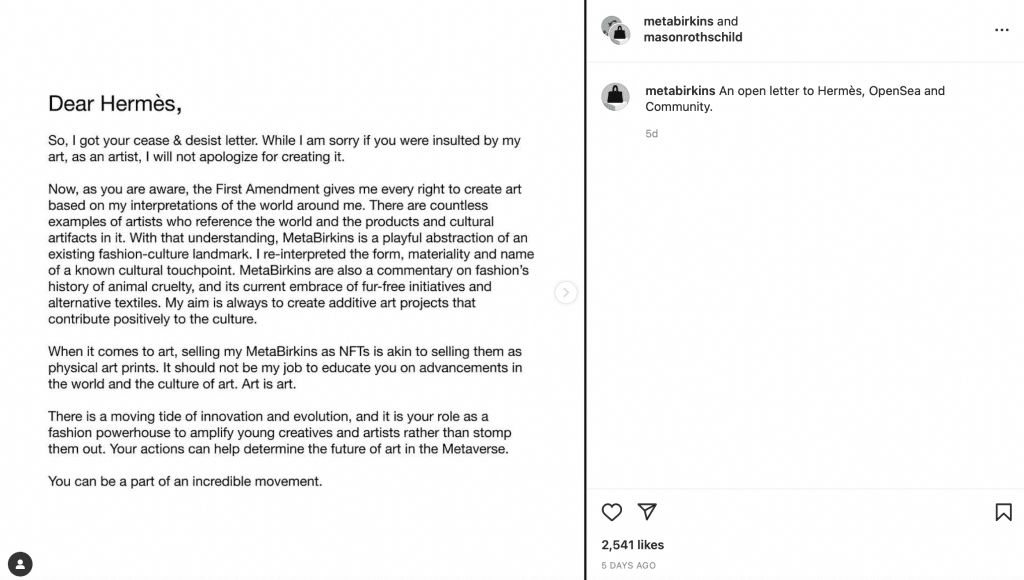

Hermès appears to have made good on its claims about non-fungible tokens (“NFTs”) that were marketed as MetaBirkins without its authorization. Creator Mason Rothschild revealed in an open letter to Hermès that he posted on his Instagram account on December 22 that he received a cease-and-desist letter from the French luxury goods brand. In a separate open letter to OpenSea, Rothschild confirmed that the MetaBirkins have been removed from the NFT platform, potentially as a result of trademark-centric takedown requests lodged by Hermès, which said in a statement earlier this month that it views the one hundred MetaBirkins NFTs as “infring[ing] upon [its] trademark rights, and an example of fake Hermès products in the metaverse.”

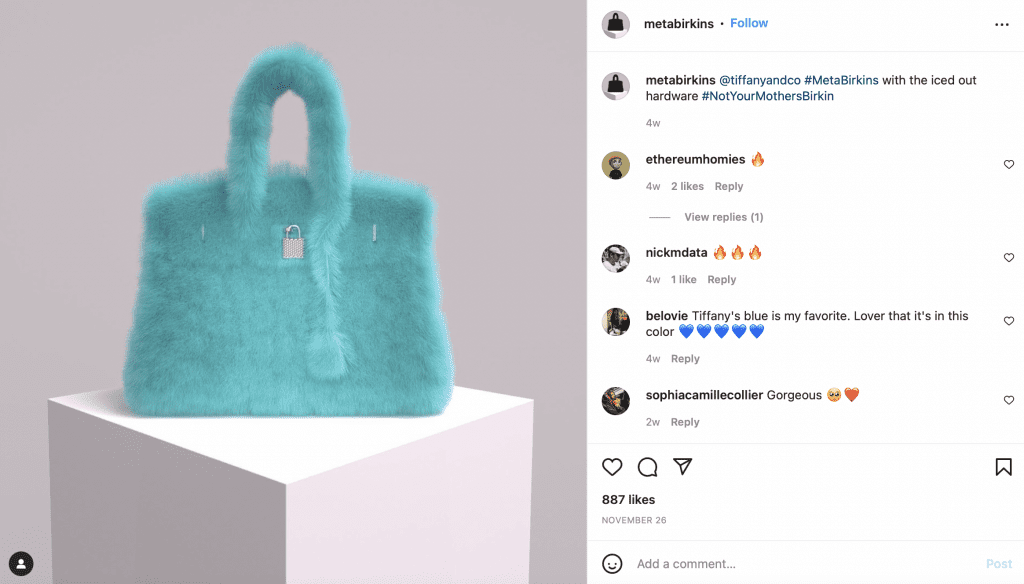

In his letter to Hermès, Rothschild argues that the MetaBirkins NFTs are shielded from Hermès’ trademark claims, asserting that “the First Amendment gives me every right to create art based on my interpretations of the world around me.” Additionally, he claims that the MetaBirkins – which currently boast a trade volume of $1.1 million, according to the MetaBirkins Rarible page – are “also a commentary on fashion’s history of animal cruelty, and its current embrace of fur-free initiatives and alternative textiles.”

Infringement and Dilution

As of now, Hermès has not filed suit in response to the MetaBirkins, which it confirmed that it “did not authorize [or] consent to the commercialization or creation of.” However, assuming it were to wage trademark claims against Rothschild, its chances of prevailing (and the relevance/strength of Rothschild’s First Amendment defense) are worthy of attention, as they raise interesting questions – and shed light on developing issues – for brands given the rise of the metaverse.

Chances are, if Hermès opts to file suit against Rothschild, it would base its suit, in large part, on trademark infringement and/or dilution claims. (It might also claim copyright infringement on the basis that Rothchild made infringing copies of its photos of the Birkin bags.) One of the most immediate issues that comes to mind on the trademark infringement front is the fact that Hermès is not actually in the business of offering up NFTs or virtual fashion. This is significant, as trademark rights in the U.S. and other first-to-use countries are amassed via use of a mark in connection with specific classes of goods/services. The marks here are the “Birkin” word mark and the design configuration of the Birkin bag, which undoubtedly serves as an indication of the source of the bag, enabling it to act as a trademark.

While Hermès maintains robust rights in the Birkin bag name and configuration for use on leather goods and other related products, there is an argument to be made that such rights do not necessarily apply to virtual handbags – or the offering up and sale of code that is tied to an image of a handbag (i.e., an NFT). Assuming that Hermès could successfully establish that its rights extend to the metaverse (maybe by relying on its rights in the Birkin bag and Birkin name in the digital/e-commerce space and/or as part of a zone of expansion argument?), in order to make a case for infringement, it would need to show that consumers are likely to be confused about the source of the MetaBirkins and/or its affiliation, connection or association with the NFTs.

As trademark experts well know, this would depend on a number of factors, including the strength of the Hermès marks, the similarity and proximity of the goods, evidence of actual confusion, the similarity of marketing channels used, the degree of caution exercised by the typical purchaser, and the defendant’s intent.

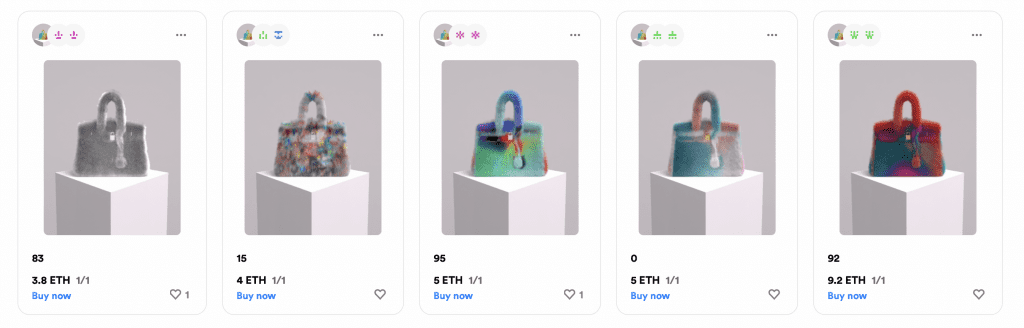

Notable here I think are a few things, including the price points, an element that may weigh in favor of potential confusion. Unlike virtual Gucci bags and other accessories that were offered up to Roblox users this spring for $10 or less at initial virtual retail, for instance, the NFT-linked MetaBirkins have sold for much higher prices. The very first MetaBirkins NFT sold for roughly $40,000, which is precisely what certain Birkins are currently selling for on resale sites like The RealReal, StockX, and Rebag. Other elements, such as the strength of the marks and the defendant’s intent might also bode well for Hermès.

Beyond that, as I noted in an earlier article on this topic, Hérmes may be able to point to the frequency with which its high fashion and luxury goods peers (Louis Vuitton, Gucci, Balenciaga, etc.) are entering into the metaverse by way of NFTs and other virtual offerings – oftentimes by way of collaborations with third parties – as support for an argument that consumers may be confused as to the source of the MetaBirkins and/or Hérmes’ affiliation with them in an initial and post-sale capacity.

Still yet, the physical versus digital divide at play here may not be the death knell for Hérmes. Rothschild, himself, downplayed the difference between the two in an interview with Yahoo early this month, saying that he believes that the distinction between physical and digital status symbols like Birkin bags is “getting a little bit blurred now because we have this new outlet, which is the metaverse, to showcase our product, showcase them in our virtual worlds, and even just show them online.”

In the event that Hérmes is unable to establish a likelihood of confusion, it would not necessarily be devoid of recourse, as trademark dilution requires no such showing of likelihood of confusion. Distinct from infringement, a claim of dilution may be made by the holder of a “famous” trademark when that mark is being used in a way that is likely to impair its distinctiveness or tarnish its reputation.

The initial inquiry here is whether the Birkin name and configuration of the bag are “famous” – or “widely recognized by the general consuming public of the U.S. as a designation of source of the goods or services of the mark’s owner.” Two of the factors that are commonly used to determine whether a mark is, in fact, famous from a dilution perspective are “the duration, extent, and geographic reach of advertising and publicity of the mark, and whether it is advertised or publicized by the owner or third parties,” and “the amount, volume, and geographic extent of sales of goods or services offered under the mark.”

With this in mind, it is worth noting that Birkin bags have been consistently offered up – both in name and design – by Hérmes since the 1980s by way of its brick-and-mortar stores. In terms of sales and out-put of the consistently in-demand bags, Hermès does not release Birkin-specific figures, but industry analysts expect that there are currently more than a million of them in the market, which translates to at least $5 billion in sales.

As for marketing and publicity, in addition to Hérmes’ own practice of advertising its Birkin bags in various mediums, the level of unsolicited media attention that the Birkin bag has received is likely unmatched by any other handbag in the market. Should Hérmes need to prove this, it would likely point to the truly sweeping number of articles that delve into the bags and books devoted to “bringing home a Birkin” to the use of the bags (and the inclusion of corresponding story lines) in television shows like Sex & The City and films, and countless paparazzi shots of Birkin bag-toting celebrities.

Taken together, such consistent use of the Birkin name and bag design by Hérmes, and the relevant sales figures, advertising, and unsolicited media – and of course, attempts to copy the design and name – would likely make it difficult to successfully argue that the Birkin is not famous, thereby, giving Hérmes the ability to make claims on this front.

Given that the federal dilution statute does not apply to non-commercial uses of a famous trademark, such as for the purpose of criticism, commentary, and/or parody, a high-level look at the “First Amendment” defense that Rothschild briefly asserts in his open letter – and the strength of that defense – is warranted.

Are the MetaBirkins Fair Use?

On the heels of reportedly receiving a cease-and-desist letter from Hérmes, Rothschild – who previously described the MetaBirkins as “a tribute to Hérmes’ most famous handbag” and “an experiment to see if I could create that same kind of illusion that [the Birkin bag] has in real life as a digital commodity” – has doubled-down on an alternative message, saying that the MetaBirkins are “a commentary on fashion’s history of animal cruelty, and its current embrace of fur-free initiatives and alternative textiles.” In that vein, Rothschild has stated that the First Amendment provides him with “every right to create art” without legal ramifications. (Such a statement, of course, fails to consider that even though the First Amendment does provide defenses against trademark and copyright claims, its protections do not come without limitations, some of which are addressed below.)

It is not immediately clear what the Hérmes-specific commentary is here, especially given that Birkin bags are not – and never have been – made from fur, faux fur, or alternative textiles. (Hérmes Victoria bag has been made in mushroom leather in limited quantities.) This lack of readily-identifiable commentary could be problematic.

At the same time, if Rothschild were to claim parody (namely, that the MetaBirkins call to mind an actual Birkin while also distinguishing the MetaBirkins “parody” from the original product), he would have to show “some articulable element of satire, ridicule, joking, or amusement” that is being communicated by the MetaBirkins and thus, that the NFTs are not merely an attempt to piggyback on – and profit from – the well-established appeal of Hérmes and its most famous offering. Again, I am not sure that the protected expressive element is immediately obvious or sufficiently specific to Hérmes as opposed to the luxury goods industry in general, which is what seems to be the real target of Rothschild’s alleged commentary.

Another potential snag to Rothschild successfully claiming fair use protection, such as parody, is the fact that the parody defense does not provide protection when the allegedly infringing use is a designation of source of the defendant’s own goods. In other words, the defense does not apply when the parodist uses the “parody” as its own trademark. Part of the question here is, thus, whether the MetaBirkins name is a designation of source of Rothschild’s collection of NFTs. I, for one, think it might be – based on the use of the MetaBirkins.com domain if nothing else.

Finally, another limitations to the First Amendment’s ability to act as a shield to trademark claims comes about when the allegedly infringing trademark is being used in a way that would create a likelihood of confusion. Reflecting on the parody defense not too long ago, King & Spalding’s Kathleen McCarthy stated that “it may be difficult to prove likelihood of confusion sufficient to meet the test for trademark infringement when faced with a ‘successful’ parody'” because when a parody is successful, it is abundantly clear that the parodist is not trading on the goodwill of the original trademark, but is using another party’s mark for the purpose of the parody. This creates little risk of consumer confusion.

However, and this might be relevant here, “If it is difficult to detect the commentary, and instead, only the brand attributes are readily apparent in the parodist’s product, the brand owner is more readily able to prove that confusion is likely,” and that the self-proclaimed parodist is benefitting from the established appeal and/or reputation of the original trademark holder.

NFTs: Now What?

There is certainly much more to unpack when it comes to the MetaBirkins NFTs and the potential (or lack of potential) for a viable fair use defense, but regardless of the chance of legal action, another question remains: What happens to the Metabirkins NFTs that have already been acquired now that OpenSea has removed them from its platform.

In short, nothing because regardless of whether an NFT is listed on – or delisted from – OpenSea, the underlying transaction is still logged on the blockchain. “The NFT still exists,” OpenSea community manager Ed Clements, told Vice about NFTs that are removed from the platform. Echoing this sentiment, Vice’s Ben Munster states that “as long as the linked image has not been removed from its source, an NFT bought on OpenSea could still be viewed on Rarible, SuperRare, or whatever — they are all just interfaces to the ledger.” And in fact, the MetaBirkins do appear on Rarible.

Stay tuned. Trademark and copyright clashes, like the one between Hérmes and Rothschild, will continue to play out as the market for NFTs and the metaverse, more generally, comes into fruition, and as the law plays catch-up with the development of new technology.

A rep for Hérmes did not respond to a request for comment about Rothschild’s open letter.