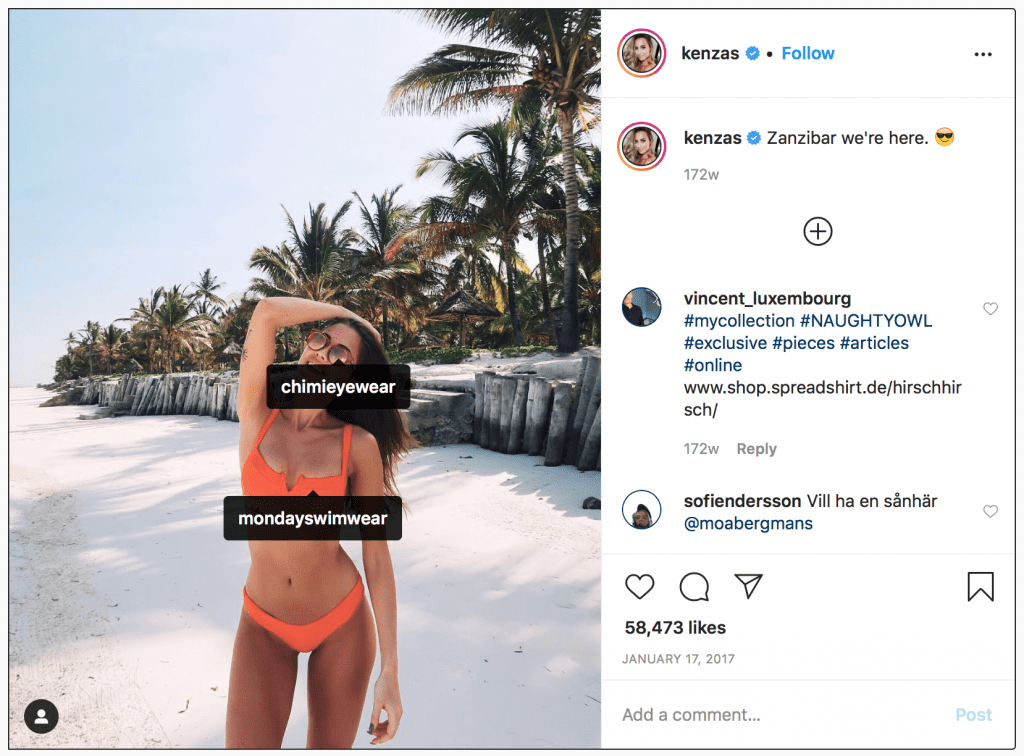

One of the biggest influencers in Sweden found herself at the center of a newly-released decision from the country’s Patent and Market Court over a handful of Instagram posts, a key case in the country’s ongoing focus on undisclosed advertising. The case got its start back in 2017 when Kenza Zouiten Subosic and a handful of other heavily-followed influencers were invited to Zanzibar by eyewear brand CHIMI. In addition to the trip, Subosic and her fellow influencers was provided with financial compensation in exchange for uploading a specified number of social media and blog posts promoting CHIMI and its sunglasses.

During the Zanzibar trip, the now-29-year old Subosic published several posts on her blog, as well as on her Instagram, Facebook and YouTube accounts in which she mentioned and/or tagged CHIMI, all while allegedly failing to clearly mark some of the content as advertising. After the trip was over, she published additional posts to her social media channels, including her Instagram account, where she now boasts more than 1 million followers, some of which were marked as sponsored posts in “collaboration” with the Swedish eyewear company.

The seeming disparity between the two sets of roughly 30 posts caught the attention of the Swedish Consumer Ombudsman, a government agency tasked with safeguarding consumer interests, which initiated legal action against Subosic’s corporate entity in January 2019 for allegedly running afoul of the Swedish Marketing Practices Act (“MPA”). According to the MPA, which regulates all marketing practices, as well as contact between businesses and consumers, across all media, any commercial message that constitute marketing must be clearly marked as such in order to alert viewers of the nature of the post.

The Law in Sweden

In its complaint, the Swedish Consumer Ombudsman alleged that at least some of Subosic’s posts did not include proper disclaimers to convey that they were the result of a partnership with CHIMI, and thus, violated the MPA and constituted unfair marketing. In response to the case, counsel for Subosic argued that the undisclosed content was posted outside the scope of the collaboration with the brand, which only required that she publish two posts, and that the additional 28 posts were the result of the fact that she simply liked the glasses.

Deciding the case, a judge for the Swedish Patent and Market Court initially stated, “The mere fact that the influencer has received a trip as payment does not mean that all posts published in connection with that trip shall be considered as marketing.” Such a restrictive interpretation would limit the influencer’s opportunities to publish pictures from trips, restaurant visits or similar activities, according to the court. More than that, the court held that just because an influencer includes or mentions a certain product from a company that she has an ongoing collaboration with in her photos, does not automatically make the posts commercial content in need of disclosure.

Against that background, the court focused exclusively on the two contractually-mandated posts (even though all 30 posts featured CHIMI’s glasses and many mentioned the company by name), and ultimately, held that neither the relevant Instagram post nor the blog post were clearly disclosed as marketing, as the “collaboration” language that Subosic used did not clearly differentiate between paid and un-paid collaborations.

The case falls neatly in line with a string of influencer-specific cases, according to Bird & Bird’s Kajsa Zenk and Karin Soderberg, who say that “previous cases have come to similar conclusions, namely, that influencers have to visibly and clearly mark posts as marketing content if compensation is involved, and it is simply not enough to just say that the post is made ‘in collaboration’ with a company, it needs to be clear whether or not the collaboration is paid for.”

Meanwhile, in the U.S. and UK

While the case may be consistent with previous decisions coming out of Sweden, it seems to stand in contrast with the rules in other jurisdictions. Early this year, for instance, the British Advertising Standards Authority (“ASA”) held that according to the UK Code of Non-broadcast Advertising, Sales Promotion and Direct Marketing (“Code”), even if a brand’s contract with an influencer does not explicitly require her to post on its behalf, if that individual does publish brand-related posts, she must spell out their relationship for her social media followers.

In that case, the ASA found that PrettyLittleThing and Molly-Mae Hague ran afoul of the UK Code when the Love Island star, who is a PrettyLittleThing brand ambassador, posted a photo of herself on Instagram wearing a coat from Manchester-based fast fashion brand and tagged the brand but failed to include disclosure language, such as #ad. Counsel for PrettyLittleThing and a rep for Hague confirmed that the post at issue “did not arise from Hague’s contractual obligations as a brand ambassador” for PrettyLittleThing, and instead, was “an organic feed post and she had tagged PrettyLittleThing in the post because she was wearing one of their products.”

Regardless of whether Hague was paid – or better yet, not paid – for the specific paid for the post at issue, the ASA still called foul, asserting in its formal determination in January that because Hague, 20, has a contractual relationship with the brand in furtherance of which she is compensated to promote its wares to her 3.6 million Instagram followers, her posts about the brand and its products fall within the scope of the UK Code, and thus, require explicit disclosure. Without such disclosure, the ASA “concluded that the post was not obviously identifiable as a marketing communication.”

Meanwhile, in the U.S., the Federal Trade Commission (“FTC”)’s rules seem to favor the latter approach, and thus, very well might require influencers to alert their followers to the commercial nature of technically unsponsored posts if they have an existing relationship with a brand. According to the FTC, “If [an influencer] endorses a product through social media, [that] endorsement message should make it obvious when you have a relationship (‘material connection’) with the brand.” Given that the FTC defines “material connection” as a brand range of instances – from a financial and/or employment relationship between and influencer and a brand to a brand “giving [an influencer] free or discounted products or services,” posts by a brand ambassadorship would seemingly fall within its bounds, potentially even for not-directly-sponsored posts.

The varying approaches to disclosure among different countries and their governing bodies reflects the very segmented rules that exist when it comes to influencer marketing, which spans countries and their laws (particularly given that so many influencers are whisked away on brand-sponsored trips and expected to create content in connection therewith). Such varying rules likely contribute to at least some of the widespread lack of disclosures and/or proper disclosure that runs rampant in the multi-billion dollar influencer economy.