Poshmark is looking to bring brands into the fold. The Redwood City, California-headquartered social commerce marketplace announced this week that “for the first time” since its founding in 2011, it is enabling “large-scale brands [to] connect directly” with its 80 million users by way of a “suite of merchandising tools and social selling features” that are specially designed to allow brands to engage with their mostly Millennial and Gen Z fans on the quickly-growing resale platform.

“We are thrilled to open our social marketplace more widely to brands, empowering them to build loyal, lasting connections with a coveted audience, tap into a new sales channel, and bring shoppers the kind of personalized service that is all too rare in ecommerce,” Manish Chandra, who is the founder and CEO of Poshmark, said in a statement this week about the new “Brand Closet” venture. He further noted that “by connecting brands directly to our community of highly engaged, deeply passionate shoppers and re-commerce enthusiasts, we’re building a stronger, more vibrant marketplace—it’s a win for everyone.”

Chandra is not wrong about Brand Closet’s apparent ability to provide benefits to both Poshmark and to brands that may opt to join the new initiative, which has been piloted with “several large brands [since 2020],” according to the 10-year-old platform. While participation in the Brand Closet program gives brands access to “enterprise-grade inventory management tools to support high-volume selling; integrated shipping; third-party logistics integration support, and dedicated customer success teams,” more fundamentally, it gives brands a place to off-load unsold merchandise. This is something that is proving to be of heightened importance than ever before as consumers and regulators, alike, wise up to the toll that fashion – and the disposal of unsold garments and accessories and/or excess textiles – takes on the environment.

The question of how to get rid of unsold goods is also becoming a particularly critical one for brands thanks to supply chain disruptions, including those brought about by the pandemic, which left brands with billions of dollars in merchandise in some cases, and with relatively limited options in how to handle it.

As TFL previously noted, during the height of the pandemic, H&M had almost $5 billion worth of merchandise on hand, and it was not alone. With stores temporarily shuttered due to government mandates and a striking slump in sales as consumers shifted their shopping priorities in the midst of a global health pandemic, brands accumulated mounting piles of garments and accessories with nowhere to go – and in many cases, the options were largely unattractive. Companies could either store the less-season-specific goods in hopes of selling them at full price at a later date (and amassing storage costs in the process) or they could mark the items way down to move them – cutting into margins and potentially, potentially incur a black mark in the eyes of consumers (depending on the brand).

But this reality is not specific to the pandemic, and in fact, close-out and off-price entities have long benefitted from the fashion industry’s long-standing inability to accurately gauge demand and thus, production volumes, which is how retailers like T.J. Maxx and co. consistently have designer labels to offer up to bargain-seeking consumers.

Brands are increasingly aiming to amass more control over how their products are marketed and sold, and in this same vein, it makes sense that they would want to have a hand in how unsold wares are managed. Feeding them into the resale market – and thereby, blurring the lines in the secondary market – is a potentially attractive opportunity, and one that at least some brands and retailers are already doing – or seemingly working towards.

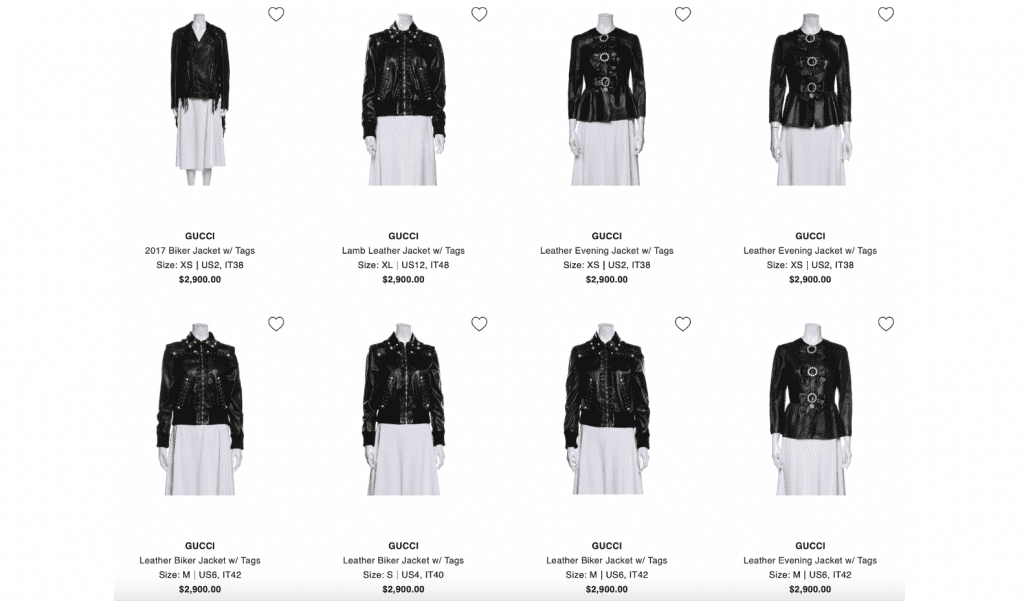

On the heels of partnering with The RealReal for a limited partnership last year, an array of Gucci garments with tags are available for purchase on the reseller’s site, which could suggest that Gucci or its authorized retailers are relying on the reseller as a way to sell out seasonal goods when the season is over. Meanwhile, Valentino recently revealed that it has partnered with four international boutiques to offer consumers access to vintage Valentino offerings by way of its website. As we mentioned in connection with Gucci’s Vault venture, it is not difficult to envision a mixture of vintage, newer pre-owned products, and carefully curated close-out goods being offered up to consumers under the same umbrella.

With its audience of ardent, young consumers, Poshmark’s Brand Closet – and other efforts, such as Vestiaire’s Brand Approved initiative, as well as in-house efforts rolled out by brands, themselves – could provide brands and retailers with a valuable tool in off-loading excess wares without having to slap a slashed price tag on them in their own stores, and risk dilution in the eyes of consumers and analysts, alike. (This may be part of the reason why top luxury groups like Kering and Chanel, for instance, have put their might behind specific resale sites, with Chanel taking a stake in Farfetch, which maintains a resale arm, and Kering investing in French platform Vestiaire Collective.)

In addition to providing a benefit for brands and retailers, the newly-launched Brand Closet program likely benefits Poshmark in at least a few of ways. Most obviously, increased sales parlay neatly into boost revenues for the publicly-traded company; this is particularly important in the resale space where margins are relatively slim. More than that, a greater selection of high-end offerings will likely cater to luxury-happy consumers in a different way than Poshmark is currently operating, which could in turn, serve to boost consumer engagement on the Poshmark site (something that it values in light of its “social commerce” focus), and also attract new shoppers that are maybe not in the market for more mass market pre-owned garments and accessories.

And still yet, by partnering with brands, Poshmark not only stands to steal market share from traditional off-price retailers by implementing liquidation elements into its web-based business, it also solidifying the sustainability of its model by adding another player – or better yet, group of players – into the equation. While Poshmark is certainly not short on sellers (it boasted 4.5 million active sellers at the end of September 2020), there is still value to be derived from the company insuring itself against the need to rely exclusively on the whims of individual sellers, and the volumes that those individuals can reasonably produce (and potential variations in that volume, as well as in seller growth and retention).

In other words, partnering with brands could give Poshmark access to a potentially more stable pool of inventory, which is, after all, the most critical element of its model, while also giving it a competitive boost in an increasingly crowded market of resale platforms, which range from luxury-focused sites like The RealReal and Vestiaire to more mass platforms like ThredUp, eBay, and even Facebook Marketplace. Now, it is just a matter of what brands will opt to open up shop on Poshmark.

THE BROAD VIEW: The big picture here is that competition is increasingly rising in the resale space, forcing existing players and new entrants, alike, to differentiate themselves and find opportunities for growth. “Companies like ThredUp and Poshmark have to demonstrate growth, and one of the things that they will probably do in the next few years is acquire other players, maybe in foreign countries,” Neil Saunders, managing director of research firm GlobalData, told Reuters this week.

Burgeoning growth in the secondary market, which is predicted to grow to $77 billion by 2025, and ultimately, even larger thanks to growing demand for resale in the Chinese market, is expected to “make the industry a magnet for deals as companies look to grow quickly to capitalize on [this] boom.” Secondary market-specific investments and consolidations have already started, with top luxury groups like Kering and Chanel, for instance, putting their might behind resale sites. Chanel holds a stake in Farfetch, which maintains a resale arm, and Kering recently invested in French platform Vestiaire Collective.

Meanwhile, Etsy snapped up Depop in a $1.62 billion deal, while sneaker and streetwear-focus entities like GOAT and Grailed have also welcomed funding within the past several months in a nod to the development of the secondary market across the board.