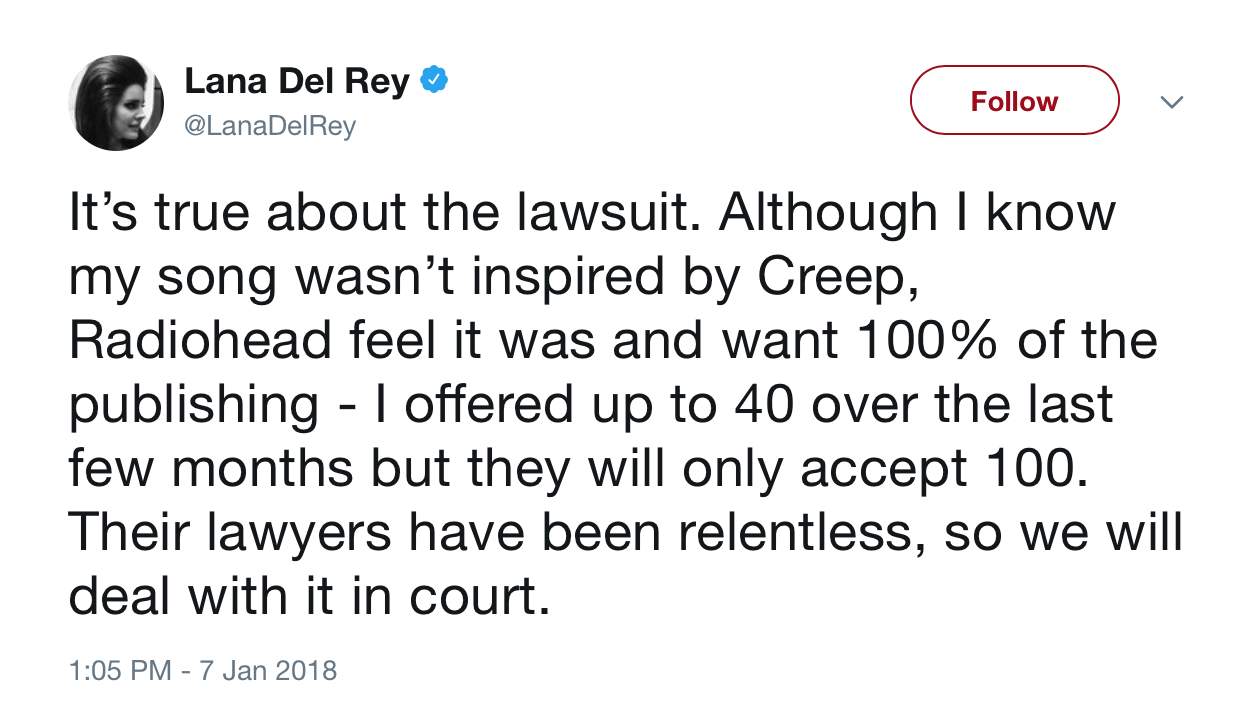

If you read last week in any publication that Lana Del Rey was being sued by Radiohead, then you were duped. You were misled because the mainstream media fell for a musician’s inaccurate and unverified tweet. Time, Pitchfork, Buzzfeed, The Guardian, Variety, CBS, The Independent, Huffington Post, People, Billboard, Entertainment Weekly, The Telegraph, Forbes, and even the BBC (and that is a highly-condensed list) all reported that Radiohead had filed a copyright lawsuit against Del Rey for allegedly co-opting its 1993 hit “Creep,” by way of her song, “Get Free.” The problem: No such lawsuit was ever filed.

A search of U.S. court dockets reveals that despite Del Rey’s tweet – which read, in part, “It’s true about the lawsuit” – no case was filed at the time of any of the articles proclaiming the legal news. This is something that the New York Times’ Ben Sisario pointed out in his article on the matter last week. “It may have been an irresistible headline: Radiohead sues Lana Del Rey!,” wrote Sisario. “The old guard versus the new. Lawyers ganging up on an artist. Copyright litigation gone amok.”

The nonexistence of initiated litigation was also pointed out by none other than a spokesman for Radiohead, who said on Tuesday, “To set the record straight, no lawsuit has been issued and Radiohead have not said they ‘will only accept 100 percent’ of the publishing of ‘Get Free.’”

The Race to Aggregate

It appears that – yet again – the race to publish led media outlets to quickly parlay reports of a rumored lawsuit, which appear to have started in the British tabloids, into articles that declared that a lawsuit had, in fact, been filed against Del Rey. This is problematic for several reasons, not least of which is that it is actual proof that many mainstream publications are doing very little, if any, research before pouncing upon and publishing at least some of their news articles.

At the heart of the issue? Aggregation. While the curation of news and the aggregation of content is not a novel journalistic technique by any means, “the past few years have seen the growth of aggregation services [and aggregation-utilizing websites] as a destination for news,” according to the Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism’s 2017 Digital News Report.

With this in mind, Angela M. Lee and Hsiang Chyi note in their article, The Rise of Online News Aggregators: Consumption and Competition, “The rise of news aggregator sites is a notable phenomenon in the contemporary media landscape. Outperforming traditional news outlets, online news aggregators, such as Yahoo News … and the Huffington Post, have become major sources of news for American audiences.”

Most of the controversy to date surrounding news aggregation has centered on “some news organizations cast[ing] blame on news aggregators for stealing their content and audiences,” according to Lee and Chyi, as well as on potential copyright claims that are born from the copying and displaying of headlines, lead paragraphs, and even entire articles, in some cases. The present instance demonstrates another marked shortcoming of the marriage between speed to publication and news aggregation: Rife inaccuracy.

The fictional Radiohead v. Lana Del Rey case is, of course, not a one-time occurrence. Many of the previously-name checked publications found themselves running afoul of the facts when they published articles highlighting a non-existent development in a bitter trademark battle involving Kylie Jenner and Kylie Minogue. Mixing up two distinct – and unrelated – legal proceedings, many publications raced to publish that “Kylie Minogue Won Her Legal War with Kylie Jenner Over Name Trademark” – in what Slate characterized as one of the most “contentious … trademark dispute[s] in recent memory.” No such victory was to be had.

In short: In order to gain the first-to-post advantage, publications opted to essentially re-print a report from the Daily Mail without confirming its accuracy. The result was the widespread publication of inaccurate information.

Given the workings of the digital landscape (and the general public’s understandable lack of legal reach aptitude), the publications responsible for misreporting do not tend to suffer as a result of their lack of research and subsequent misconveyance of the facts. In large part, this is because the general public does not know of the reporting fallacies. Most readers are: a) Not often in the habit of confirming news reported by legitimate websites, and certainly not in the habit of digging into legal databases for verification of the claims made by such news-proffering sites; and b) not otherwise privy to the ins-and-outs of a newsworthy event. This is precisely why publications that provide news exist. They exist to save the public the time of having to do their own news-related research.

First but Not Best

While the resources available to reporters and journalists, and the ease with which they can be accessed, are greater than ever before, the shift to digital media has not uniformly resulted in better researched or more aptly cited articles. Instead, the result is, for the most part, a vastly sped-up publishing cycle that often lacks transparency. As Dartmouth College professor and columnist Brendan Nyhan, who has written extensively on the accuracy of breaking news coverage, told me around the time of the Kylie v. Kylie news mix up, “There is pressure on everyone to be first and to correct later, if at all.”

This lack of balance between speed and accuracy runs rampant in part because “the disincentives of being wrong are so weak,” says Nyhan. “Most inaccurate stories are never corrected or removed, and even if a correction is made, it rarely attracts the same audience as the initial sensationalized article.” Now add to that the increasing reliance by publications on news aggregation sans any meaningful editorial oversight or fact-checking.

The result is not fake news in the most traditional sense, which is a term with a very specific definition (i.e., entirely fabricated stories put forth for political or monetary gain). Such reporting also likely does not commence with the intent to be entirely clickbait journalism at its worst.

However, regardless of the intentions in play, the publication of aggregated news (or any news) sans verification of the claims set forth, is little more than the sum of either of those dirty journalistic elements and it does not appear to be going away any time soon.