A high fashion textile firm claims in a new lawsuit that Valentino has “illegally enriched” itself through its unauthorized use of copyright-protected fabrics and trade secret stitching techniques. According to the complaint that it filed in a New York federal court on March 25, Mrinalini, Inc. claims that Valentino S.p.A. and its American arm Valentino U.S.A., Inc. (“Valentino”) are on the hook for “taking, using and copying [Mrinalini’s] designs and swatches,” passing them off as its own designs, and failing to pay for them, giving rise to copyright infringement, trade secret misappropriation, unfair competition, unjust enrichment, conversion, and breach of contract claims.

Setting the stage in the newly-filed complaint, Mrinalini claims that it has maintained a relationship with Valentino for over fifteen years, starting work with the Italian fashion brand back in the early 2000’s when the New York-based garment and textile firm claims that it was “already doing design work for other design houses, including Ralph Lauren, Fendi, Etro, and Diane von Furstenberg.” Over the course of the parties’ years of work together, Mrinalini asserts that there have been “many occasions where Valentino used and sold fabric designs that were wholly original to Mrinalini,” something that the company argues has “happened from the earliest days of the relationship up to the present.”

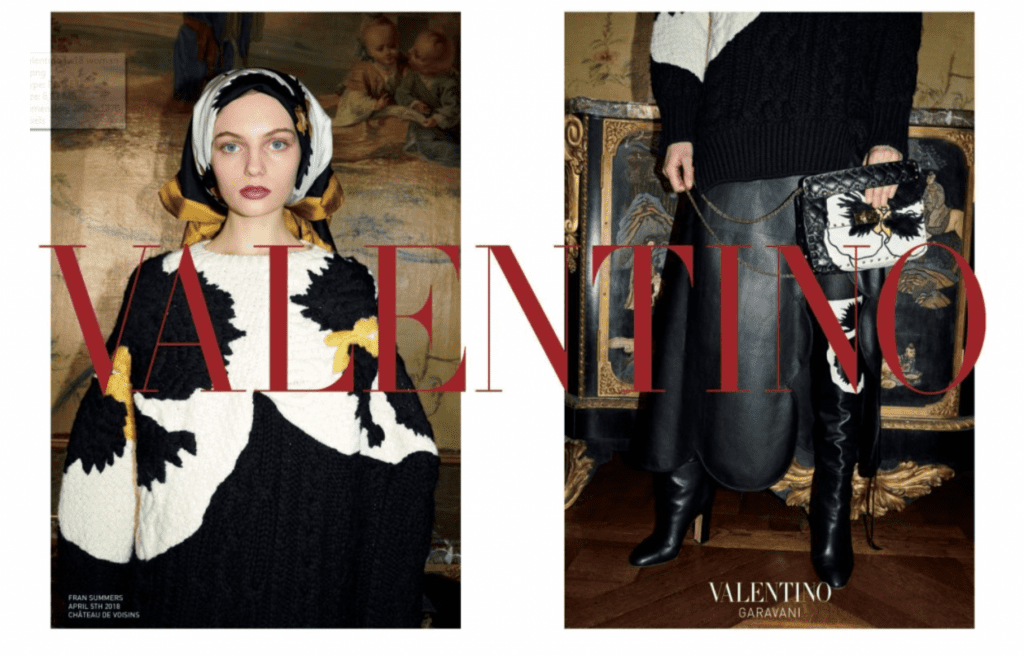

Mayhoola-owned Valentino has “even taken complete, original dresses and other garments from Mrinalini, and shown them publicly on fashion runways, falsely passing them off as if they were created by Valentino,” Mrinalini claims, asserting that the brand failed to give it “credit, recognition, and compensation” in the process.

Aside from to allegedly passing off Mrinalini’s work as its own, including copyright-protected fabric designs, which Valentino allegedly co-opted for couture collections, thereby, giving rise to copyright infringement and unfair competition, Mrinalini claims in the newly-initiated lawsuit that Valentino has engaged in trade secret misappropriation. Specifically, Mrinalini alleges that it “pioneered sewing techniques like its ‘Intarsia’ technique, which is an intricate way to join several pieces of fabric into a rich and textured whole, elegant to meet the tastes of sophisticated clientele,” and which has “resulted in materials not seen before in the industry,” and that has become “heavily in demand in the high fashion world.”

Allegedly impressed with its Intarsia technique, and in light of the relationship between the two parties, one in which Mrinalini claims that it would present Valentino with “completely original designs and techniques, with the understanding and agreement that Valentino would pay for such designs and techniques if it used them” and/or Valentino “would invite Mrinalini to present specific fabric designs and swatches based on suggestions of varying specificity from Valentino,” Mrinalini contends that in or around 2013, Valentino changed “many of its commercial and runway offerings” to make use of textiles created by way of the sewing technique.

But not only did Valentino start incorporating pieces created by way of the Intarsia technique, Mrinalini argues that Valentino sought out specific details about the technique, including photos and videos from the manufacturing process, which Mrinalini claims that shared with the brand – albeit “only after Valentino agreed to keep the photos and video confidential.” This agreement was “at least implied if not express,” Mrinalini asserts, noting that the brand “later affirmed its obligations under the agreement in writing.”

Despite agreeing to keep such information confidential, Mrinalini alleges that Valentino employees shared the proprietary stitching techniques with “other suppliers, including Mrinalini competitors, apparently in an unscrupulous effort to source … large quantities of clothing for Valentino … [from] the cheapest supplier, all without permission from Mrinalini.” Beyond that, Valentino allegedly “induced another [one] of its suppliers, Shevie, to hire people Mrinalini had trained in the Intarsia technique,” which Valentino and Shevie did, per Mrinalini, “to gain improper access to the Intarsia technique and misappropriate Mrinalini’s trade secret for [its own benefit].”

As a result of such alleged wrongdoing, Mrinalini claims that “Valentino – one of the largest fashion names in the world, has earned profits from Mrinalini’s proprietary designs and techniques that range well into the tens of millions of dollars, if not higher.”

In addition to arguing that Valentino has engaged in copyright infringement and pointing to an array of different instances in which Valentino allegedly “copied the expression covered by [one of Mrinalini’s copyright] registrations without permission [for] clothing items,” Mrinalini cites claims of trade secret misappropriation and breach of contract in connection with the brand’s alleged use of the Intarsia technique. Making its trade secret claim, including the critical element that it took “reasonable measures” to protect the trade secret, Mrinalini contends that since it developed the “secret stitching technique,” it has taken “reasonable measures to maintain the technique in secret.” Among other things, it asserts that “only a few trusted workers, subject to confidentiality obligations, know the technique on a need-to- know basis.”

“Though the technique is used to make clothing that is sold widely around the world,” Mrinalini alleges that “skilled artisans cannot learn anything about the technique from inspecting clothing made with the technique.” In fact, it argues that “Valentino itself had tried to learn the technique, but could not do so until it used improper and dishonest methods.” Valentino misappropriated this trade secret information – and breached its agreement with Mrinalini – when it shared the technique with others, including competitors, for its own benefit, Mrinalini argues.

The fashion house also engaged in unfair competition, according to Mrinalini, when it “took complete and original products from Mrinalini and passed them off as its own, both on runways and in stores,” which the textile company says “is sometimes referred to as ‘reverse passing off.’”

With the foregoing in mind, Mrinalini is seeking monetary damages, including a disgorgement of Valentino’s profits in connection with such alleged wrongdoing, injunctive relief to bar the brand from “further wrongful activity, including further trade secret misappropriation, copying and unfair competition,” and an order from the court requiring Valentino offer up for destruction “any remaining inventory of wrongful goods.”

It is not difficult to imagine Valentino pushing back against Mrinalini’s claims on the basis that it has seemingly known about such alleged infringement and/or misappropriation for close to two decades and not taken action sooner. As for making a successful trade secret case, that is no small feat. The complexity of such cases, and any potential defenses at issue, is only heightened by the fact that it can be “a difficult task to convince a jury that a trade secret exists, that it has been stolen, and that the misappropriation caused harm,” DLA Piper’s Andrew Valentine has previously stated, pointing to the Huawei Technologies and Futurewei Technologies v. CNEX Labs and Yiren Ronnie Huang, and the Six Dimensions, Inc. v. Perficient Inc. cases, among others, as examples of this.

More than merely convincing a jury, these matters are further muddied by the fact that quantifying the damages owed to the aggrieved party as a result of the alleged misappropriation can be complicated. This is often the case because dollar figures can be difficult to ascertain for things, such as know-how, manufacturing processes, and business practices, for instance, thereby, making these cases complicated and expensive to litigate.

A representative for Valentino did not respond to a request for comment on the lawsuit.

The case is Mrinalini, Inc v. Valentino S.p.A., et al., 1:22-cv-02453 (SDNY).